Whereas HBO’s previous best-shows-ever The Sopranos and The Wire have been crime dramas, their miniseries Chernobyl is clearly of the awkwardly named ‘disaster movie’ genre. Which says it all, really. Narratives focused on a disaster have, until now, been a preserve of the cinema, and haven’t really been done on the small screen.

The genre has a long history, and favours some sorts of disasters more than others. Earthquakes, volcanoes, and meteors, your big, beefy disasters, are ready-made examples of the kind of spectacle the flicks love. (1974’s The Towering Inferno was essentially Die Hard with a fire instead of terrorists.) Ditto things going wrong with ships and planes. Everyone knows Titanic, and cinema in the ‘70s saw so many aeroplanes in peril that it kicked off Leslie Nielsen’s career as a deadpan comic marvel in the 1980 spoof Airplane!.

But the funny thing is that radiation, by contrast, has never seen all that much screentime – practically none if you discount nuclear weapons being used as MacGuffins in rough, tough action films. Beyond that, it largely serves in comic book adaptations as a magic bullet, a way of explaining where superheroes got their powers on par with ‘a wizard did it’.

The Chernobyl miniseries had plenty of spectacle, but that’s not something inherent to radiation. Indeed, the fire sequence in the first episode is something of a red herring. The true threat, as becomes all too clear very quickly, isn’t the fire itself, but rather, the unassuming lump of graphite on the ground. Despite the scene where we behold the ghostly sight of the exploded reactor core, it’s the grit and debris that’s actually killing people. T.S. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land, written in 1922, included the line ‘I will show you fear in a handful of dust’ – sixty years later, it came horrifyingly true.

The last serious drama to use nuclear power as a central plot device was The China Syndrome, all the way back in 1979, and despite some rave reviews at the time it was obviously helped by the Three Mile Island accident happening less than two weeks after its release. Even this is an outlier in terms of taking the subject seriously. As the cinema A-list has it, it’s usually James Bond waving a rod of plutonium about in a way that would probably render him infertile.

On TV, meanwhile, radiation’s most prominent representation was on The Simpsons, in its full glowing-green cartoon form. This was an extended post-Chernobyl joke about callous corporations borne of the ‘90s zeitgeist, but thanks to the longevity of The Simpsons, it’s still going today. Given that this was such a period-specific reference, it’s been suggested that the show should have transferred Homer to other careers which held poor reputations, such as flash-in-the-pan dotcoms (early 2000s), the finance industry (late 2000s), and pharmaceuticals (until the opioid crisis is abated).

But, thanks to this legacy gag and the show’s lasting success, many now rank America’s favourite non-prehistoric cartoon family right up there with the Chernobyl disaster in terms of damaging the nuclear industry’s image. The disaster, to the great relief of everyone on the planet, only happened once, but The Simpsons will be syndicated every night in the developed world for the foreseeable future.

So The Simpsons, more-or-less alone in the media landscape, would feature the occasional meltdown scare and nuclear accident, but these were always played fairly lightly. They didn’t have a body count. (At one point, Homer was praised for “turning a potential Chernobyl into a mere Three Mile Island”.) In the light of the miniseries, this all rings somewhat sour. The point remains, though, radioactivity and nuclear energy simply isn’t that prominent in cinema and television – insert your own joke about ‘background radiation’.

Meanwhile, in the medium of video games, you can’t move for radiation. Sometimes quite literally, when it’s used as a kind of the-floor-is-lava type hazard. The tragically unfinished Half-Life series, its name itself a reference to radioactive decay, was possibly the ur-example of simply painting the lava green and calling it nuclear waste. Despite the name, it wasn’t particularly ‘hard’ science fiction, but the original was set in the kind of off-the-grid research facility you might expect to have such things lying around.

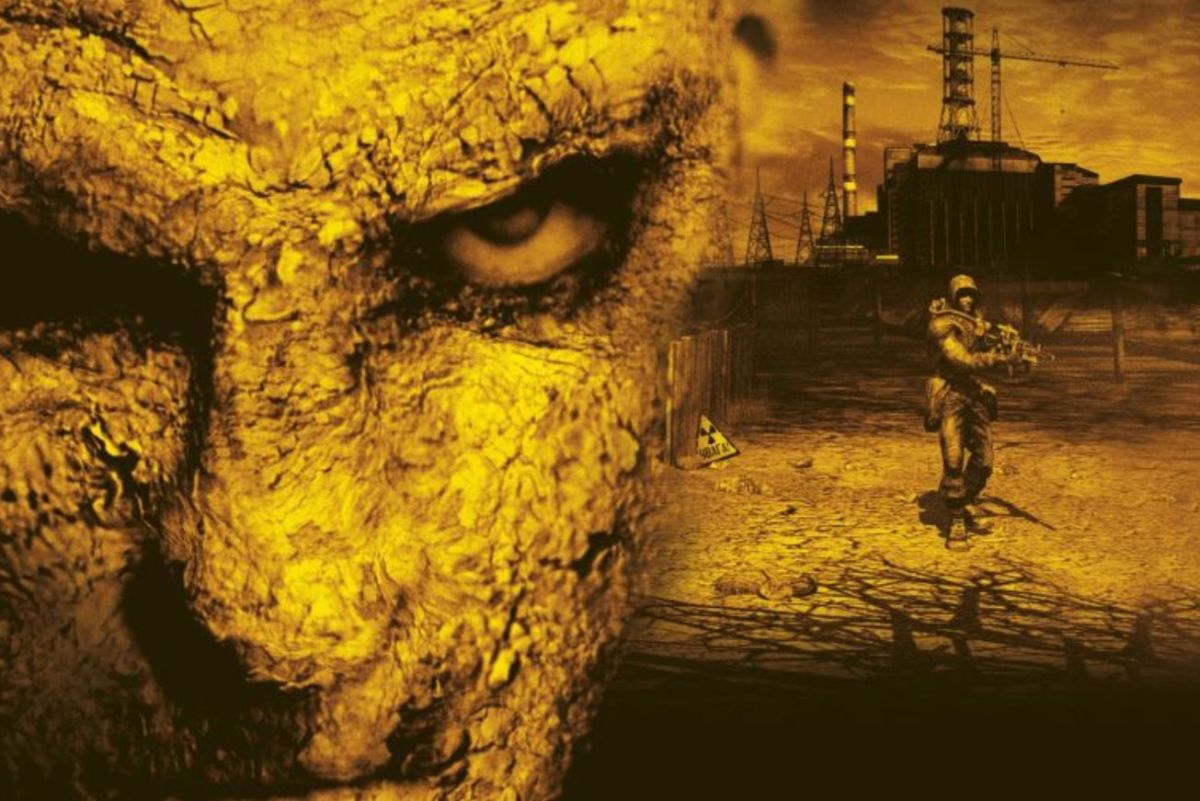

Slightly more realistic was the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. series (one of which was actually called ‘Shadow of Chernobyl’), whose radiation had no cues beyond the crackling of a Geiger counter and your health starting to wane. Of course, I say ‘slightly more realistic’ with good reason, as S.T.A.L.K.E.R. was also heavy on the old trope of using radiation as an excuse to stick in mutants and monsters.

‘Shadow of Chernobyl’ applied in more sense than one. Yes, the games took place in and around the stricken power plant and the surrounding exclusion zone, but they also had an overriding post-Soviet aesthetic. This wasn’t just a matter of thick accents, though it had those aplenty. The architecture, down to errant propaganda posters, was all dead-on, a product of the games having been as immaculately researched as the miniseries.

Possibly the most popular example of all may be Bethesda’s Fallout series, which fulfils the broken promise of the Cold War and presents life in the wasteland left after a worldwide nuclear exchange. In the old tradition, it uses radiation as a kind of ad hoc fencing, where there are some areas which actively harmed you. And, as with S.T.A.L.K.E.R., it uses this background as an excuse to play fast and loose with realism, including laser guns, robots, and, yes, irradiated mutants.

Even beyond the power plant, the exclusion zone itself has seen some memorable depictions in games. Most notably, there was the Pripyat sequence in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare, easily the best level that the semi-annual shooter franchise has ever turned out. When we saw that distinctive indoor swimming pool in the miniseries, a good number of young men in the audience would have remembered it as the setting of a frantic gun battle with terrorists.

The Modern Warfare level might had invisible walls along its edges marked by little signs warning of hazardous radiation levels, where if you crossed the boundary, you’d start to die. But, like S.T.A.L.K.E.R. before it, Modern Warfare presented a frighteningly atmospheric recreation of Pripyat and the exclusion zone. The picture-perfect realism was something the miniseries was praised extensively for, including by many who lived in the Soviet Union. Inaccuracies are on the level of ‘that pen, on that desk, in the background, behind that fern, says the year is 1989 rather than 1986’.

On a much, much wider scale, video games are also happier depicting nuclear weapons – not simply as looming threats, like in The Hunt For Red October, but actually being used. For every attempt by works like 24 to raise the stakes by letting off a nuke, Gandhi had launched a hundred in the strategy game Civilisation,. (Initially a bug, Gandhi being a bloodthirsty warmonger with his finger on the button became one of the franchise’s most endearing features.) Most real-time strategy games set in the modern era give you the chance to push the button yourself. From the Age of Empires-alike Empire Earth to the tinpot dictator simulator Tropico, when the player’s back is to the wall the mushroom clouds start popping up.

In video games, life is cheaper. If the player character dies, they respawn seconds later, sometimes at a hospital, sometimes paying a few in-game pennies for the privilege, but returned to life hale and hearty. It’s for this reason that games’ attempts to inspire genuine pathos are a double-edged sword. It was the Call of Duty series that gave us the infamous ‘No Russian’ level, where the player can gun down crowds of unarmed civilians. This was meant to be an atrocity even by the standards of those incredibly violent games, but it’s exactly what people have always been doing in Grand Theft Auto.

Life is fairly cheap in the miniseries too, but without the respawning, this carries all the weight that statement should. The miners, the soldiers, the cleanup crews, we see all these people stoically accepting that performing these necessary tasks may well kill them. Those poor souls who clean the roof of the power plant are termed ‘bio-robots’, a euphemism to rival any of the figurative language the military’s ever used for threats to life and limb. And yet, well aware of the dangers, they do it willingly. For all that the miniseries represents a searing indictment of life under Soviet rule, this is collectivism in its noblest form. It’s the same principle of simply chucking bodies at the problem as the human wave tactics used by the Soviets in World War II – still known, in Russia, as ‘the great patriotic war’.

The faithful often define God as something which you cannot see or smell or touch, but which nonetheless exists. You’ll notice this description could all-too-easily apply to radiation, along with the Almighty’s habit of killing anyone who even looks at them the wrong way. A great number of gods in the classical pantheons represented the terrifying powers of nature, and, at their worst, natural disasters. Poseidon unleashed tsunamis, Vulcan caused volcanic eruptions, and so forth.

Where radiation differs from the established set of disasters is that it’s a man-made beast. This could be said to apply to stuff like Titanic and the various films where people are trapped on aeroplanes as well, but the action in these is usually kicked off by some adverse influence, be it an iceberg or a terrorist attack. It’s very rarely a case of man’s own hubris coming back to bite him in the arse, as it was with Chernobyl.

The Wire, to return to HBO’s greatest hits, was always conceived of by creator David Simon as a Greek tragedy, with bureaucratic institutions taking the place of the gods as the great impersonal forces to whom the individual is but a plaything. You’re likely already seeing the parallels with Chernobyl here. Some committee cheaps out on building a nuclear reactor (which sounds like such a good idea, doesn’t it) and half of Eastern Europe gets irradiated. Soviet officials who wouldn’t know plutonium from Pluto the cartoon dog don’t want the embarrassment of admitting how this happened, and everyone’s looking down the barrel of the exact same thing happening again.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iHxBTJUVzOY

For all that Paul Ritter’s Dyatlov provides an easy figure to blame, as the narrative explicitly points out, there is no one individual responsible for the horrors unleashed by the Chernobyl disaster. It’s just systems, feeding into each other, creating consequences that no single person would sign off on, and when the full picture finally comes out, it’s more horrifying than anyone involved would have dared imagine.

Despite the way popularity is usually figured as a matter of appealing to the lowest common denominator, the common factor with the various best-shows-ever, from The Sopranos in the early 2000s up to Chernobyl now, is a complexity of narrative which stands out from the crowd. This isn’t to say they didn’t have other good qualities, but even with a cursory view you could tell these weren’t straightforward stories of good and bad. (The Sopranos may not have been the first TV show to centre on an antihero, but it certainly brought the setup to mainstream prominence.)

At the risk of indulging in stereotypes, this complexity may be key to understanding why radiation has traditionally been more prominent in video games. Not necessarily the complexity of the narrative, but rather that of the underlying science. Consider your archetypal gamer, a sexless, obsessive, pencil-necked geek. For all their faults, they are a good deal more likely to have even a passing awareness of the dangers of radioactivity, certainly more likely than the average viewer of The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills. Like I said, stereotypes.

But while both the foul-smelling gamers and airheaded celebrity-lovers probably take exception to the way I’m describing them, what we can probably all agree on is that the increasing complexity of popular media, be that the complexity of its plotlines or its subject matter, is a good thing. This isn’t me prescribing opinions to the general public: one of the main points of criticism audiences had with the final season of Game of Thrones was the lack of complexity and nuance by comparison to the earlier seasons. In other words, that’s what got people watching in the first place. There is clearly a market out there for dark, complicated, unusual stuff like Chernobyl, and the world is better for it.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.