At some point in the 90s a young Michael Cumming was working as a director for a corporate video for British Gas, and thinking that he should be doing, in his words, ‘anything else’. And because fate isn’t always a cruel mistress, he ran into Chris Morris, high on the horse off the back of his successes with news-spoofs On The Hour and The Day Today.

They got to talking about how best to fill a supermarket with water (a weird prefiguring of the wacky, out-there hypothetical interview questions used by Google and the like) and the rest is history…

When Brass Eye was released in 1997 it took the British media landscape by storm – not least because of its most notorious aspect, getting celebrities and public figures and other talking heads to read out complete nonsense, completely sincerely, to camera. There was the protests against the dangers of ‘heavy electricity’, the campaign to save an elephant that had its trunk stuck up its arse, and most famously of all, public information spots about a new legal drug from Czechoslovakia called ‘Cake’ (‘Cake is a made-up drug…it’s not made from plants, it’s made from chemicals, by…sick bastards!’)

But far from being a primitive version of youtube’s ‘it’s just a prank, bro’ genre – the kind of thing tossed off in twenty minutes by half-drunk frat boys – a full two years of blood, sweat, and love went into Brass Eye. Oxide Ghosts is the story of how that happened – or at least, the best glimpse we’re likely to get. Chris Morris, contra his Satanic newsreader persona, is famously camera-shy, rarely if ever giving interviews. However, Cumming does specify that the film – made up largely from material from Cumming’s own archive – goes out with Morris’s blessing.

The ‘oxide’ refers to the accumulation of the substance on the tapes – because of course that’s how far back it was, we’re dealing with physical tape-based formats, the kind of thing that you could literally rewind. And the ghosts? That can only be Morris (in his many disguises – Ted Maul, Austen Tassletyne, etc). Even though Cumming is there in person to present the film, Morris hangs over his introduction like the spectre of newsreading past – and a huge amount of the film itself has Morris front and centre. Indeed, Cumming invokes the spirit of Morris (the ‘one-off man-mental’) to dissuade any would-be pirates. The intention was always for this to be a cinema-only event – something for the hard core of fans, the stalkery anorak-clad obsessives, who Cumming actually invokes quite fondly.

A lot of the actual material is, it must be said, unused sections from the show – yet it would be unfair to dismiss it as a glorified blooper reel. One thing that becomes quite clear is the sheer volume of material that went into the show, pared ruthlessly down to size by Morris’s infamously exacting editing process. Many of the sections, for instance, are expansions of well-known and well-loved bits from the show itself. Some of this is improvisation, which naturally comes thick and fast when you turn Morris loose on a halfwitted celebrity, but just as much is rigorously scripted and structured.

One example of this is ‘Sutcliffe! The Musical’, the stage version of the exploits of the Yorkshire Ripper, starring Peter Sutcliffe as himself. The musical numbers – seen only in fragments in Brass Eye itself – are given a bit more of an outing here. We also get some background on the billboard advert for ‘Sutcliffe!’ displayed in Piccadilly Circus, which Cumming’s voiceover teasingly suggests could have easily been CGIed – only to then reveal they simply rented the space and did it for real. (Startingly, none of the people passing beneath it actually noticed.)

We also get an expanded version of the drugged-up board meeting at Shaftesbury’s Jams – which was actually part of the ‘Decline’ episode, but does seem to be a very obvious refugee from the ‘Drugs’ episode. Perhaps in the editing room, Morris or Cumming or both felt it was too similar to the Drumlake School segment. Either way, to hear someone wetly insist on how delicate a flavour loganberry is while surrounded by drug-taking of the most top rank is worth the admission price on its own.

‘Drugs’, of course, featured the infamous ‘Britain’s streets are so awash with drugs not even the dealers know them all‘ section: covert camera footage of Morris approaching actual cocaine dealers and asking to buy ‘yellow benteens’, ‘triple sod’, and – this one really infuriated the dealers – ‘clarky cat’. As Cumming related in the Q&A afterward, this had been around as an idea since the very start – Morris had a long list of things he wanted to do, one of which was ‘try to score drugs while dressed in a nappy wearing a space-hopper on his head’, which of course he did, clutching a teddy-bear that concealed a microphone.

One recurrent theme in the film (and simply looking at the series in retrospect) is the idea that ‘you couldn’t do this now’ – that, in today’s era of instant information, Morris could not pass himself off as an anonymous newscaster and pose stupid questions to celebrities. In the case of the clarky cat bit, though, it was a case of ‘you couldn’t do it then, either’ – it won’t be controversial to say that Channel 4’s executives would never have signed off on such an undertaking. Neither did anyone bother to ask them – it was a matter of Morris, Cumming and their team simply going out and doing it, guerilla style.

We learn that, in the first contact, Morris had borrowed a tactic from close-to-the-knuckle reporters in the field of hard news, and stuffed a copy of Vogue up his shirt – the idea being to reduce any knifings he might suffer to the non-fatal level. As it turned out he had no reason to fear, and the dealers were in fact more intimidated by him – assuming, not unfairly, that the tall, well-bred man from the home counties talking absolute nonsense was actually an undercover policeman. Having visited the dealers once in mufti and once in space-hopper and nappy, there were plans to have him return in a horse-drawn carriage wearing Victorian finery and ask for a tincture of opium – which sadly fell through.

(The Q&A also shed some light on the part of that sequence where a dealer angrily insists that his wares are ‘not wood’ – some of the production team had visited the dealers themselves beforehand, to test the water as it were, and one had come away with a block of wood wrapped in clingfilm.)

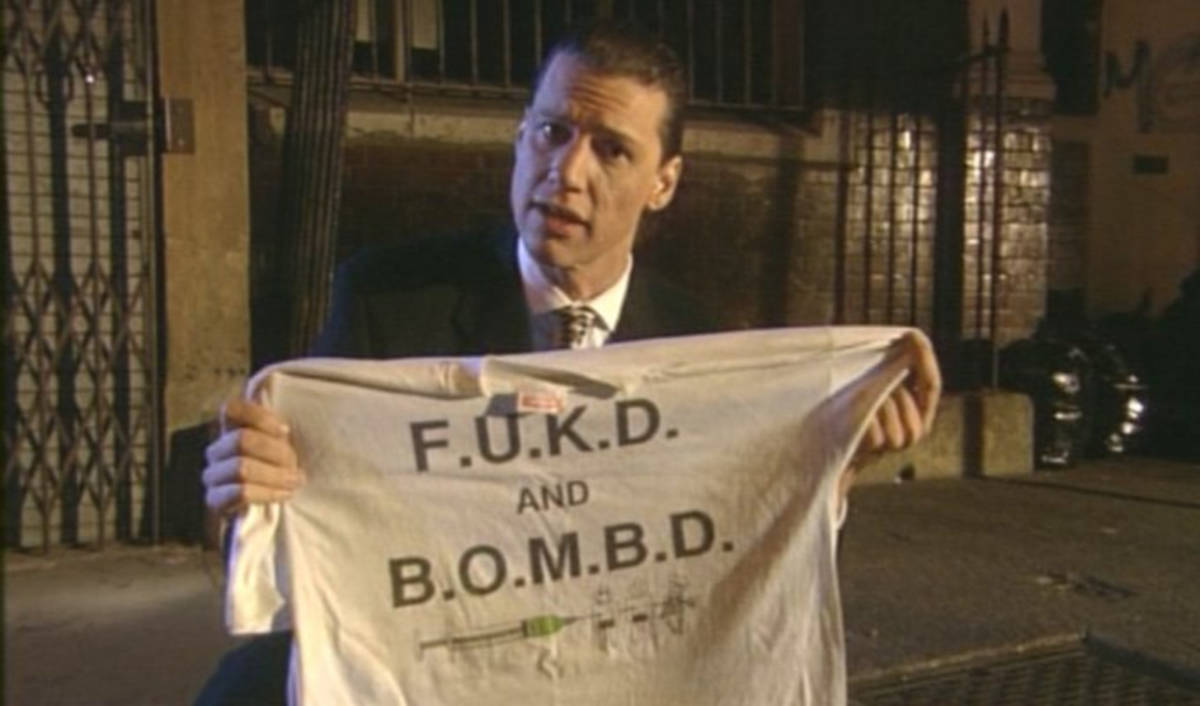

It was the ‘Drugs’ episode that featured the legendary ‘cake’ sequence, which reached its apotheosis when it prompted MP David Amess, MP, to actually call for the banning of cake in parliament. Until the heat death of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and possibly well beyond, Hansard will bear it out in black and white that David Amess called for legislation to outlaw cake, proudly acting on behalf of the fictional organisations Free the United Kingdom from Drugs and British Opposition to Metabolically Bisturbile Drugs.

Surprisingly, though, Amess wasn’t even the biggest fish in this particular net – Morris also bagged the then-vice-chairman of the Conservative party, Graham Bright. Bright, like many of the celebrities featured, complained. Unlike many of the celebrities featured, he had sufficient clout to actually force the excision of the footage that featured him denouncing the menace of Cake. (Something he can’t have been all that sincere about – given that unlike Amess he never raised the matter in parliament.)

Apparatchiks of John Major’s grey little government weren’t the only old crooks to have had their noses tweaked by the Brass Eye team, though. The film also treats us to a recording of Reggie Kray – he of the Kray twins, once kings of British gangland – speaking from prison to put out the word on behalf of Karla, the elephant who got her trunk stuck in her arse. Reggie was induced to do a second take, having mispronounced the name of animal rights organisation AAAAAAAZ – yes, he hadn’t drawn out the A enough. Reggie, like Bright, eventually realised he was being played for a mug, and sent a tough boy over to the purported headquarters of AAAAAAAZ – who was informed, truthfully, that there was no such organisation.

But possibly the most charming part of the film – and this is speaking as a serious fan – is not the expanded sketches, deleted scenes, and so forth, but the actual bloopers, the glimpses between the cracks. As mentioned above, Morris shuns interviews, so to see video-era recordings of him corpsing makes you feel oddly warm. It’s as if he has cast off the much-vaunted ‘media terrorist’ persona for a bit, and you at long last get a glimpse of the man behind the man, the man who came up with the profoundly silly ideas that were at the core of Brass Eye, like the naval vessel where the crew must report for duty naked, and the little Irish girl who beheld Mother Mary driving around at night.

As mentioned, Cumming did a Q&A afterwards – one advantage of a film having a very limited cinema-only realise – and, I’m ashamed to say, I gave into my cynical hack-journo instincts and asked if there had been any moments of creative friction between him and Morris, hoping for something lurid. The answer was an emphatic no, and deep down, I think I already knew that. Between writing and presenting, Morris was such a central creative force that there couldn’t have been disagreement, that there didn’t need to be. Cumming came off throughout as being as much of a Brass Eye fanboy as the rest of the audience, gleefully quoting lines from the series.

Someone else posed a far more interesting question, asking Cumming if any of the various celebrities who had been interviewed had worked out what was going on. Most, apparently, were laughably credulous – he cited Vanessa Feltz mouthing lunacy about the murder of Marvin Gaye and then asking if they’d like another take – but the one who came closest was Chris Eubank, former middleweight champion boxer and host of ‘Youth Hosteling With Chris Eubank‘.

Eubank was apparently in a weird, ‘Temptations of Jean-Claude Killy’ post-sports-fame phase, that Cumming described as ‘driving around Brighton in a monster truck’. Eubank apparently demanded the interview take place on Brighton beach, then – having arrived to filming equipment all set up on the beach – refused to film there, prompting them to relocate to a nearby hotel. Midway through, he broke off to make a call, and then returned somewhat subdued and reticent.

This anecdote came off as surprisingly bittersweet, since apparently Cumming had really wanted to have Eubank on Brass Eye. He went on to describe the one usable bit that came of that interview, in which Morris began to talk about ‘the fabric of society’, then produced a swatch of different fabrics and asked Eubank which was the closest fit (Eubank chose the hessian over the parachute silk). Which seems like it could have slotted quite neatly into a ‘speak your brains’ segment or celebrity interview medley.

Like Brass Eye itself, Oxide Ghosts has been edited down into an easily digestible lump, from hundreds of hours of tape which Cumming keeps in a big box. And while the film has only a very limited release, there is the hint of more. Apparently not long after its release, Morris called up Cumming to inform him he had a big box of his own, and to ask whether he would like it. Cumming replied that yes, he would like to get his hands on Morris’s big box. So maybe, just maybe, we’ll have the chance to experience more unseen Brass Eye material in the future – and if this is any indication it’ll be well worth it.

Oxide Ghosts is scheduled to be screened at selected locations around the UK between now and December 19th – catch it while you can.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.