Speaking of the League, there’s a character drawn from Iain Sinclair’s work in the latter volumes of that who, through magic or other mysterious things, is confined within the geographical boundaries of Greater London, yet can move freely through its timespan. And this seems to be an idea Moore revisits in Jerusalem, with the first volume’s chapters skipping seamlessly between colourful characters from the many time periods of Northampton. When I say ‘seamlessly’ I mean it – characters bleed into each others’ chapters with little regard for chronology, and it doesn’t seem that odd beyond the reader’s moment of shocked recognition.

If you had to point to main characters in the work, the obvious choices are the Warren siblings, Alma and Mick – yet you wouldn’t go far wrong citing Northampton itself. It is after all the only constant, and Moore deftly places it both as backdrop, and squarely front and centre. The book cannot disguise its affection for the city, battered and burnt though it may be – and we see a good bit of the battering and burning firsthand. Northampton being Moore’s hometown, you might accuse him of favouritism when he paints it as a kind of central lodestone of the British country and culture – but Moore is so in his element dealing with the historic and the mystic that you find yourself wanting to believe it.

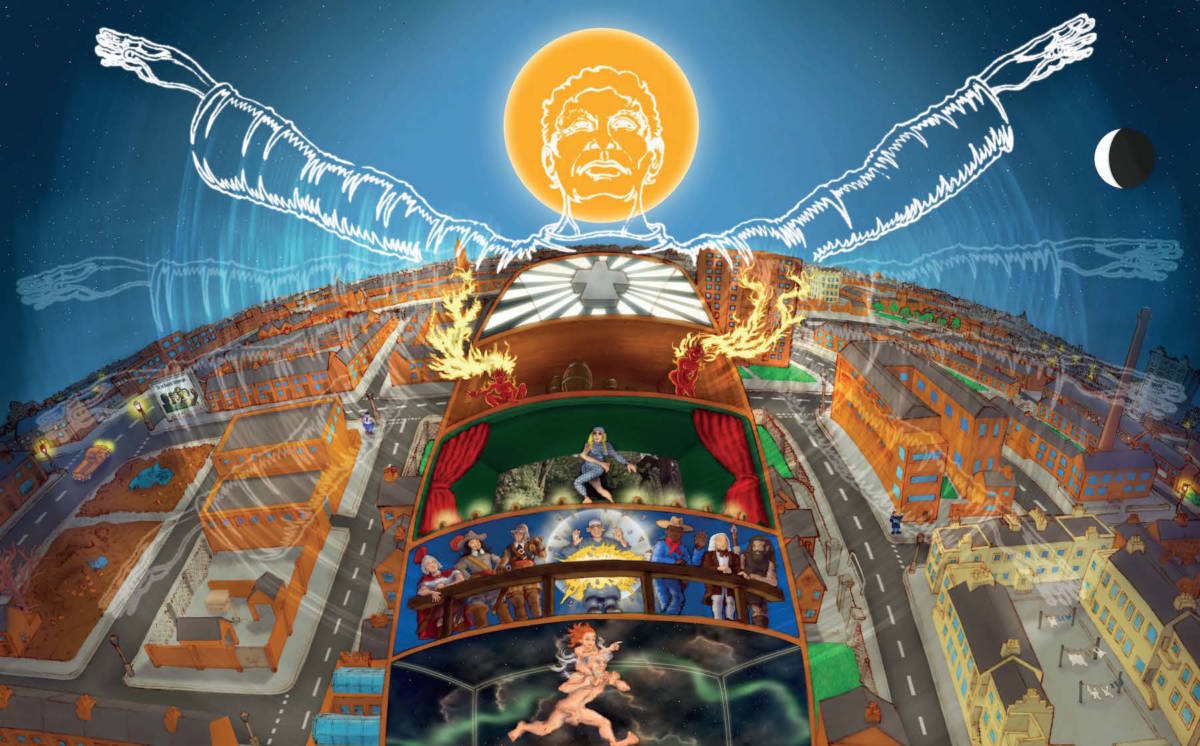

And the mysticism runs through the book like a stick of Brighton rock – to the point you may as well dispense with such an adolescent label as ‘mystic’ and call it what it is, theology. He’s already cheerfully screwing about with time, so if you thought for a second Moore would confine himself to this earthly plane of existence you’re a blind fool. Like the crazy long-haired magic-man he is, he weaves an astral plane/afterlife/fifth dimension that is at once bizarre and strangely recognisable, which serves as the setting of the second volume. You could only ever mistake it for an Abrahamic idea of heaven, hell, or even limbo if you viewed it through a kaleidoscope, but then that’s more-or-less how most prophets tend to look at things.

(Speaking of prophecy, the book frequently makes mention of two particularly grim tower blocks in the centre of Northampton, which have ‘Newlife’ written down their sides in big silver letters, a legend which fools nobody. Various characters look up at them and think ‘they’re gonna catch fire, and people are gonna die and this crook local government’s going to be to blame’. The other shoe doesn’t drop within the book – in fact it didn’t at all until ten months after the book’s release, and the Grenfell tower disaster.)

Moore even takes this beyond playing around with the nature of reality within the book, and at times messes with the reader’s – adopting some unusual ways of writing. Some are relatively subtle, like the precocious writer of the Dead Dead Gang’s chapter being styled like the children’s books she will eventually write, while some are obvious, like the homeless poet whose bad experience with datura is rendered entirely in verse. At one point, Moore even goes so far as to have an entire chapter in the language-mangled style of James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake – and he actually pulls it off, too.

The prose, it should be said, is about as florid as the average florist’s. Moore hasn’t toned down the verbosity he uses in comic scripts at all, if anything he’s letting loose here – a cigarette lighter imbued with a little momentary importance becomes a ‘stick of amethyst’. It’s possibly most comparable to a less antiquated version of H. P. Lovecraft’s writing, which I once saw best described as ‘purple like a clotted bruise’ – and Moore is no stranger to Lovecraft. You could argue this style is only appropriate, given the weighty, reality-bending subject matter, but then you could also argue these things combine into some kind of superweapon of pretension – essentially it’s like Marmite, you’ll either love it or hate it.

Now, Moore’s been criticised before for including rape as a plot point in a lot of his works – and yes, for the potential reader’s sake if nothing else, it does come up here. However, the way he deals with it is really just a subset of his views on sex more generally, and this isn’t to mean he uses the incredibly iffy technique of eroticising rape (unlike a certain fantasy tv series I could mention). Moore doesn’t shy away from depicting sex as simply a fun thing, he’s experimented with pornography-as-art before, and as a natural extension of that, he doesn’t shrink from treating rape as the vicious corruption of sex that it is. That dynamic’s in full effect here. The scene is presented in gut-squirming detail, and the perpetrator is presented as unambiguously evil – which is saying something in a book where a demon eventually finds redemption. I’m not saying it’s not unpleasant subject matter, but on balance, there’s not much to criticise Moore himself for – if it had been written by Andrea Dworkin nobody would blink at it.

Given Moore’s conviction for acid dealing at the tender age of 17, it would be a little hackneyed to describe the book as a trip – but it is, a trip through Northampton’s corners and centuries, and I’d go further even, it’s a journey. Each chapter’s new viewpoint character takes you by the hand – some more tenderly than others – and leads you further into this world that is at once familiar and outlandish. This is an image that actually crops up in the third volume when painter and vision-receiver Snowy Vernall takes his dead granddaughter for a scenic wander through all of reality itself.

If you’re on the fence about what I’ve described so far, then the best I can suggest is testing the waters with some League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (not the film, this isn’t a nursery) before you take the plunge. If on the other hand you like the sound of this, and/or are a Moore fan already, there really isn’t a reservation to be had. The only possible disappointment is that, when you come to the end, whatever black magic he’s clearly trying to weave won’t have made the rest of the world better.

Join Amazon Kindle Unlimited 30-Day Free Trial

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.