The Far Cry games are something like a summer holiday in first-person shooter form, with half the appeal being the setting – scenic, open for exploration, and teeming with angry armed men. Over the years it’s become one of Ubisoft’s AAA reliables, with Far Cry 6 (actually the eleventh game in the franchise) eagerly anticipated later this year. In case you’ve missed any of the games – quite possible, since the franchise has been going since 2004 – here’s a potted history of Far Cry so far.

The History of the Far Cry Games

The Beginning (Far Cry, Far Cry Instincts, Far Cry Instincts: Evolution)

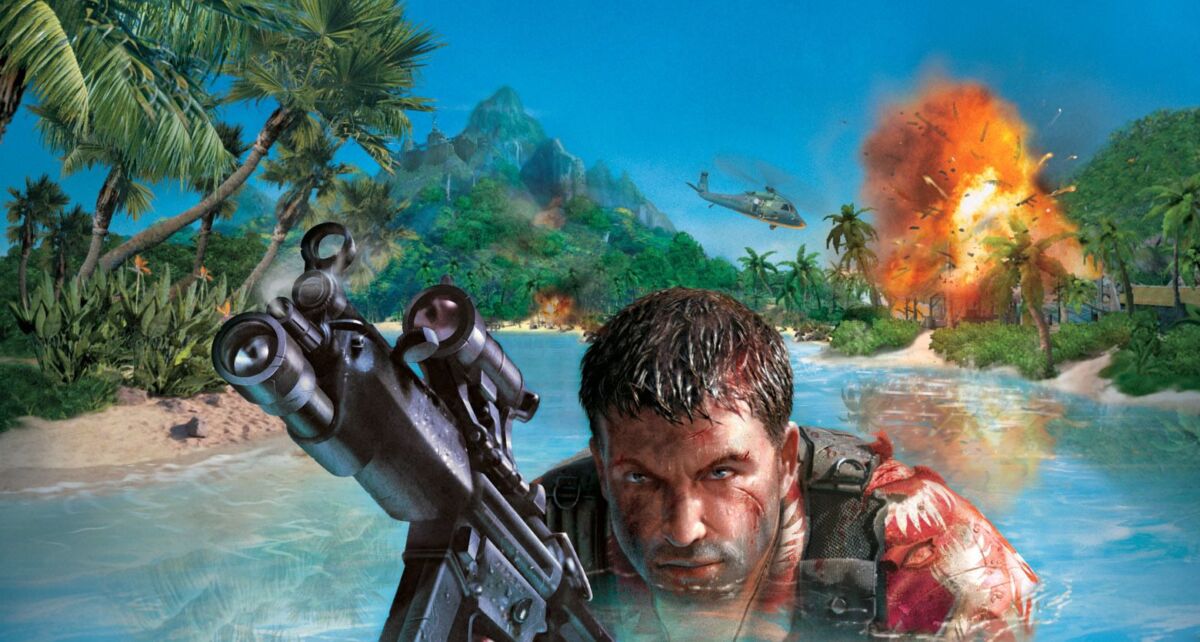

The original Far Cry was one of those games with such grand ambitions that they couldn’t help but exceed its reach. There were stealth mechanics, of a sort, but how this played out in practice was with enemies zeroing in on you through half a mile of dense, steaming jungle. Anyone who actually played it as a stealth game rather than running in and shooting the baddies would have ended up eating their controller in frustration.

But the preternatural-seeming enemies were a side-effect of trying to make the enemy AI actually clever, in the same way as Half-Life – and like Half-Life, Far Cry was roundly praised for this. Most reviews offered at least a little nod to either the AI or the graphics, and usually both. It was celebrated as “nigh-perfect” and “quite possibly the best one-player, action-intensive shooter ever” – granted that was back in 2004, but still.

Before the first Far Cry was even released, it was already being treated to one of the most dubious honours a game can be granted – a film adaptation by the famously terrible director Uwe Boll. When the film inevitably bombed, LP Pharand of Ubisoft Montreal was reasonably even-handed in his response, saying “We aren’t against the idea of a Far Cry movie, we are against the idea of Uwe Boll making a Far Cry movie.”

Thankfully, this wasn’t the only adaptation. Far Cry 1 made its way over to the Xbox in slightly more linear form as Far Cry Instincts, which – as if to illustrate the scope of the game’s ambition – had to be more linear because the Xbox couldn’t cope with the large open world. Instincts got its own mini-sequel, Evolution, which was essentially more of the same. No bad thing for a remake that had averaged between an eight and nine out of ten with the critics.

The Rumble In The Jungle (Far Cry 2)

Far Cry 2’s gameplay wasn’t much less clumsy than its predecessor. This was a world where, every time you drove through a junction, armed men would immediately start chasing after you. Functional stealth mechanics were still a long way off. But Far Cry 2 did introduce the grimily realistic mechanic of your guns suffering wear and tear, and ultimately jamming on you during firefights – which played into the bleakness of the game’s strongest element, its story.

Instead of the B-movie monsters of the original, Far Cry 2 opted for realism that went past ‘gritty’ and actually often got pretty unpleasant. Heavily inspired by Joseph Conrad’s Heart Of Darkness and its loose film adaptation Apocalypse Now, you played a mercenary who’d been dropped into a war-torn African country in search of an arms dealer known only as The Jackal. You end up fighting for both sides of the civil war, and consorting mainly with other mercenaries, since your guns are the only real way to interact with the world. Suffice to say, you do not play a nice person. Side missions include seeking out caches of blood diamonds, and picking up medication for your steadily advancing malaria.

The Jackal was mainly present as a series of rambling, nihilistic audio logs dotted throughout the game, but nonetheless was easily the game’s strongest character. What’s perhaps telling here is that Jack Carver, the player character from the original Far Cry, didn’t return for the second because the players didn’t really know or care who he was. This is perhaps unavoidable in video games, where the protagonist must on some level be an empty shell for the player to jump into (curiously, resolutely silent protagonists like Zelda’s Link and Half-Life’s Gordon Freeman are often more memorable than your Jack Carvers). But either way, this left a vacuum for characters with personality that the villains have been eager to fill – as we will see.

Where the first Far Cry had been on a fairly generic tropical island, the second presented an open world you genuinely wanted to explore. Locations ranged from bare desert to deep jungle, with a sprawling map of 31 square miles – about the same size as Grand Theft Auto V, a game released five years later.

The critics (and indeed anyone who played it) were quick to single out the obviously annoying features: unjamming your gun, taking your meds, and the constant stream enemies with nothing better to do than chase you down. But in spite of these flaws, Far Cry 2 enjoyed the same kind of warm reception as its predecessor, with practically no scores dropping anywhere below an eight out of ten.

The Tyrant On The Island (Far Cry 3, Far Cry 3: Blood Dragon)

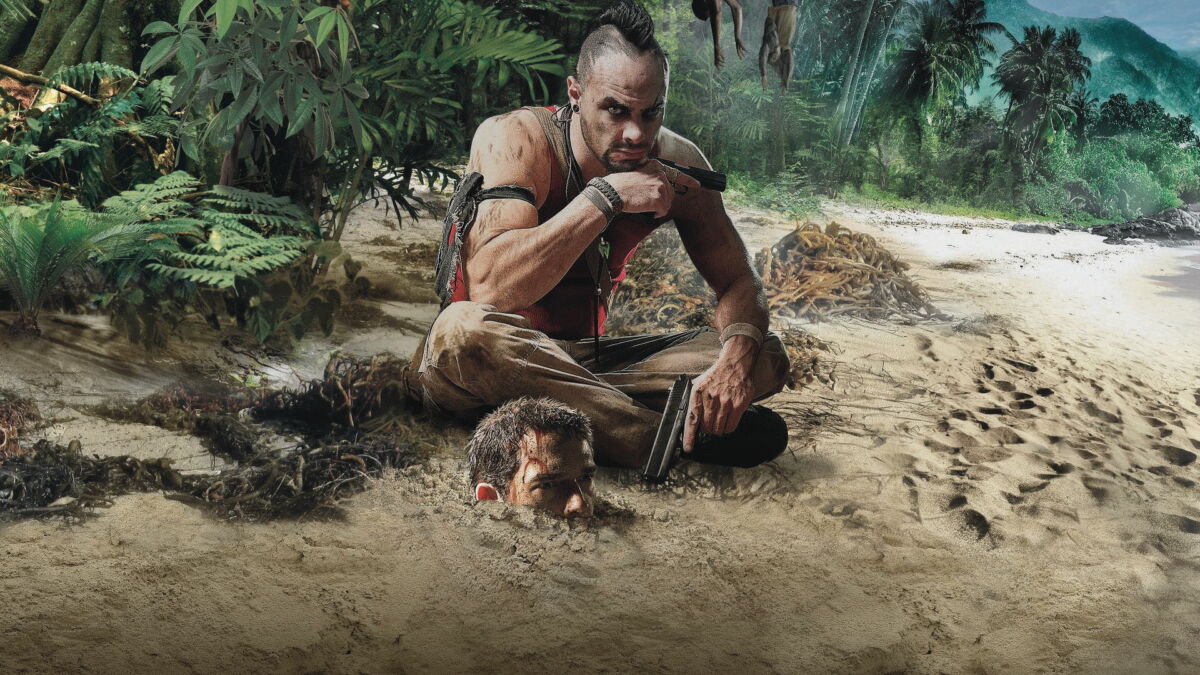

Far Cry 3 could be said to have kicked off the franchise as we know it today. They finally had the hardware to make the stealth mechanics work properly, and the combat went beyond ‘fire in their direction until they stop moving’. You could now be reasonably expected to land a headshot, and what’s more, it introduced close combat.

The previous entries had, technically, included close combat, in the sense of ‘swipe ineffectually at them with a knife that might as well be blunt’. Now you could creep up behind someone and run them through with a machete, right from the first mission. And as you advanced through the game, you’d unlock more ways to do people in like this – after hacking down one enemy, you could spring over to the next and slice them up too, or pull your victim’s sidearm and wipe out their friends. Not for nothing did Cracked once point to the best part of Far Cry 3 as being its ‘freestyle murder system’.

Far Cry 3’s story made none of the pretensions of illustrating the evils of war we’d seen with Far Cry 2 – instead it was big, bold, and stupid. Its centrepiece was Michael Mando’s Vaas, a loud, larger-than-life villain who by nature was a lot more appealing than the white-bread protagonist or his tedious pals.

Far Cry 3 also brought in a staple of Ubisoft’s other big-hitter Assassin’s Creed, which has infected a few too many open world games – a tower in the middle of each sub-region, that you climb up to get a cinematic pan around the nearby landscape. This was a bit of a feature of the franchise for a while, but by Far Cry 5 the game was rightly taking the piss out of the idea.

Far Cry 3 was the revolution, where all the experimental fumblings of the first two instalments finally paid off, and this showed in the critical reviews, which mostly hovered around a more-than-respectable nine out of ten. It racked up a baker’s dozen of awards, and more than a few for Vaas specifically, with his ‘did I ever tell you the definition of insanity?’ speech picked out as a particular highlight.

Like Grand Theft Auto, it had been with the third entry in the franchise that things solidified into what we now think of as Far Cry – and like Grand Theft Auto, one numbered instalment doesn’t necessarily follow on from the next. The next entry was Far Cry 3: Blood Dragon, which turned the dial up from its story merely being silly to absolutely ludicrous. It adopted the neon-swathed, synth-heavy aesthetic that is the fever-dream approximation of what the 1980s were like.

Blood Dragon wasn’t just a title, either. The usual predatory fauna were joined by gigantic, laser-breathing lizards, a perfect fit for its over-the-top approach. It was obviously a sideshow, much less substantial than Far Cry 3 and pretty much the definition of DLC, but still universally hailed as a fun little blast.

The Shouting On The Mountain (Far Cry 4, Far Cry Primal)

Far Cry 4 wasn’t a huge advance from Far Cry 3. It was, by and large, mechanically identical, feeling more like an expansion pack than a true sequel – but even so it was a bloody good expansion pack, providing a lovely new locale (the definitely-not-Nepal fictional nation of Kyrat), lots more toys to play with, and not one but five hammy villains to shake your fist at. After the success of Far Cry 3, it seemed like Ubisoft had established a baseline and were now refining it, seeing what worked and what didn’t.

It also featured a couple of arcade-style minigames, one of which had flamboyant main baddy Pagan regularly chiming in on the radio to comment on what you were up to, like a Greek chorus. Like Vaas before him, in the face of some fairly bland protagonists he couldn’t help but steal the show.

Far Cry 4 got solid reviews across the board. The harshest criticisms were mainly that it wasn’t much of a leap from Far Cry 3, and even then, one element that got mentioned a lot was the vertical exploration of Kyrat’s mountainous terrain adding in a new dimension.

With the creators perhaps aware of how similar Far Cry 4 was to Far Cry 3, the next entry in the franchise took things in a dramatically different direction – prehistoric. Far Cry Primal traded guns and explosives for sticks and stones, taking the action all the way back to 10,000 BC, somewhere in what might one day become central Europe. Instead of quad-bikes and technicals, you could tame and then ride around on a sabre-toothed tiger.

In the end, Primal was more divisive than Far Cry’s previous entries, either being greeted as a breath of fresh air or condemned as a repetitive boondoggle – although even the harshest critics rated it an above-average three out of five, and found time to praise the unbroken primeval setting and the animal-training dynamic, unrealistic as it might have been. The public, too, could only find so much to complain about, and in February 2016 it was the best-selling game in the United States.

Going Bananas In Montana (Far Cry 5, Far Cry: New Dawn)

Far Cry 5 returned to a contemporary setting, with all the guns and explosives that suggests, but rejected the franchise’s usual exotic locales in favour of bringing all the same action to a rural region of Montana – here under the thumb of a doomsday cult who (much like Bioshock Infinite) go around swathed in nakedly Christian imagery without ever actually invoking the C-word.

Far Cry 5’s reviews were some of the most divisive yet, with many finding its well-worn cultist characters a bit flat compared to the florid likes of Vaas and Pagan. Either way, though, it was the fastest-selling title in the history of the franchise, doubling the sales of Far Cry 4, shifting over 70,000 copies in its first week. This time, it wasn’t just the critics praising the combination of good graphics and pretty setting – Far Cry 5 was actually embraced as a PR tool by the state of Montana’s tourist board, who pleasingly seem to have taken the whole ‘they’re overrun by an evil cult’ plotline in good fun. Like hunting and fishing? Why not try it in real life? Although please don’t blow anything up.

At the risk of spoiling how Far Cry 5’s doomsday prophecies turn out, its own non-numbered spinoff New Dawn took place in a post-nuclear wasteland. But, rather than the usual grimy, grey post-apocalypse so beloved by, for example, the Fallout games, New Dawn took the opportunity to make its landscapes more lush yet, with the wreckage of civilisation being reclaimed by nature.

EGM gave it a particularly harsh two out of five, noting that like its own post-apocalyptic civilisation, New Dawn was mostly recycled from the spare parts of what had gone before. It drew more positive reviews elsewhere, but even these noted that it was all very similar to Far Cry 5 – far more similar than the other minor entries Blood Dragon and Primal had been to the games they were spun off from.

The Future (Far Cry 6)

There is, of course, a Far Cry 6 on the way later this year, with go-to villain actor Giancarlo Esposito as the latest evil and charismatic final boss. As we’ve established, Ubisoft have been refining these games down to their strongest parts for a while now. Ultimately, though, the core formula of open-world first-person-shooting seems set to stay in place for a long time to come. There’ll be tweaks and fiddles, little quality-of-life advances, but in the end – ironically, since 6 will have you rise up in revolt against Esposito’s tinpot dictator – it’s evolution, not revolution.

READ MORE: The Comforting Familiarity of the Far Cry Games

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.