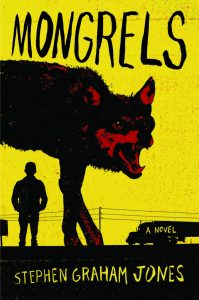

Stephen Graham Jones has twenty-three books and over two hundred and fifty short stories under his belt. This incredibly talented and prolific writer was kind enough to sit down and talk with me about werewolves, the alchemy of silver, horror, and his new novel Mongrels.

So, do you know any good werewolf jokes?

I don’t. Not because there aren’t any. I’m sure there are. It’s that I have a complete inability to either remember or tell jokes. Which is to say, the one or two jokes I can remember—I think I just remember one, actually—I always start laughing right when I start telling it, because I know what the punchline is. Except I never get there. Because of all the laughing, and pleading with people to wait, please, that I’ll get this under control soon. Which, now that I’m saying this all out-loud where I can hear it, I bet that’s why I tend to write by the seat of my pants, as opposed to mapping everything out. I want to be ambushed by the punchline, by the ending, by the surprise resolution or final gesture or whatever I luck into. I always want to stumble into Woody Allen’s joke at the end of Annie Hall, just, with different words and context and all that, so I don’t look obviously derivative. Even though I am.

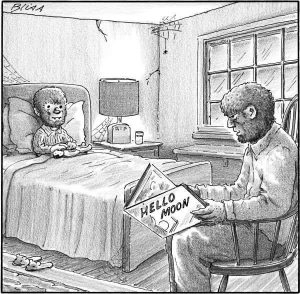

But, talking werewolf jokes in particular, mostly what I have stockpiled are single-panel comic-strip type things. Gary Larson, man, that guy could always reel off a panel that could both undercut and bolster the whole history of werewolf lore. And, I wonder if there maybe even are more visual werewolf gags than verbal? I mean, the werewolf has grown up in the twentieth century largely at the cineplex, right? Guess that could suggest or support that the humor associated with it might end up being similarly visual. There’s so many cool werewolf gifs, too. This is online, right? Here’s a werewolf single-panel job someone (Robert R.M. MacNamara) posted on social media just yesterday, which pretty much sums up all werewolf humor:

How much wolf do you think is in a werewolf in human form and how much humanity is in a werewolf in wolf form?

Did this used to be a woodchuck question? But, it’s kind about how much you try to tamp the wolf down, I suppose. Red in Mongrels, say. He doesn’t really try at all. Darren doesn’t either, so much. But Libby does. As to how much human persists in the wolf, the way Mongrels works, anyway, you get more control, the more you shift. But you’re never just a human mind at the wolf-controls. That’s kind of the joy and thrill and ‘lesson’ of werewolf stories: that instinct overrides intellect. It’s why we keep telling ourselves werewolves stories—because we need that reminder. Especially right now this very moment, when we’re trying to download as much of ourselves as we can into our phones and social media. What all that does is pretend a divorce from the body, yet the product is something we still want to call ourselves, something we still want to call ‘human.’ But we’re not just minds. We’re animals, with animal appetites and animal urges. If we don’t get out under the fool moon and play the beast every now and again, then, well. That beast’ll rise all the same. More you try to tamp it down, the more bitey it gets.

What’s your favorite werewolf movie and why?

Ginger Snaps. It’s not what was I weaned on—that’s The Howling—but . . . maybe I should start with two of my very favorite-most scenes in all of moviedom. One’s that vampire royalty woman walking through that about-to-be-crazy train in Underworld. The other is Ginger, halfway wolfed out but pretending it’s a costume, walking through the Halloween Party in Ginger Snaps. Both of those, they’re a woman who completely and absolutely owns that whole scene. It’s really powerful—it’s Tamara, back in the halls at school. But, yeah, things go south in Underworld once the werewolves get there, of course. And Ginger doesn’t get everything she wants from the party, really. But it’s these moments before, these dilated, almost slow-motion moments—they’re what I live for, when I go to the movies.

Too, Ginger Snaps is just some powerhouse movie making. That opening sequence? It’s right up there with—with Ghost Ship, say. This is a little grail-touchy, but I would say it even maybe approaches the opening sequence of Scream. And then the initial contact with the werewolf, that’s ripped straight from An American Werewolf in London—a solid eighty percent of werewolf stories, they’re “stay on the path”-stories. They’re Little Red Riding Hood. And these two sisters living in their insanely sane little suburban house, trying to deal with one of them growing a tail, trying to deal with making out in back seats with boys . . . man. Just all of it. I need to watch this one again. Thanks for the remind.

The idea of silver being deadly to werewolves is integral to Mongrels and one of the few wild speculations in the book to be proven true. Why did you choose to perpetuate this myth, as opposed to, say, werewolves having their animal nature at the mercy of the moon?

The moon never made sense to me, as a transformation trigger. Just, I can’t figure out any real difference in sunlight and moonlight, except degree, and context. And, okay, enculturation, if that’s a real word. Like Wade Davis says about the “zombies” he finds: if you believe, then you can change. The moon is so associated with the werewolf that, once you get bit, you expect so hard to change with the full moon that maybe you just do. But, I mean, would a quarter moon have some effect? Is there some unique property the moon’s regolith has that for some crazy reason triggers things in creatures that have never been up there? I’m not saying it can’t work. Just, I couldn’t get it to. But, as for where this moon-association starts, that’s easy: The Satyricon. So, way back, yeah. But, as for why the association? I think it’s just as simple as that, in the deep dark woods, you see more scary wolves about when the moon’s full. Because there’s more light. So we kicked up a causal explanation. And a thousand truck stop t-shirts can’t be wrong, can they?

Silver, though. Man, I traced silver down through the ages. I talked to medievalists and big time retired folklorists and scientists and on and on, trying to track silver down. I mean, I completely get why the werewolf needs silver—every monster needs an Achilles’ heel, something we puny humans can apply our human intelligence to, and win the day, thus telling the kiddos to stay in school, brains are good, all that. Zombies have head shots, vampires have the sun—you’re hardly a monster if you don’t have some little nothing that can kill you. War of the Worlds, anyone? As for where werewolves got their silver bullet . . . there’s a lot of stories. Which is wonderful. The Beast of Gevaudan story kind of had it retconned in in the thirties, sure, but for the longest time, there was really no difference between witches and werewolves, and silver was always pretty killer to witches, so, makes sense it would sting a werewolf. The earliest story I can find is 1640, in Griefswald, Germany, where some students rallied against werewolves by melting down all the town’s silver—that old story, yeah, which ends with “intelligence” winning the day. Which is a story we humans really really like to hear told, as our intelligence is really all we’ve got, against fangs and claws and magic and the rest. However, as to why silver got deadly to witches? Was it its association with churches, an association that would of course help against “evil” monsters? Was is that silver is actually antimicrobial, meaning werewolves, being these big balls of infection, would of course be weakened in that antimicrobial presence? Really, what I think? I think there’s some association between silver and the moon that I haven’t quite uncovered yet. A friend who studied a lot of alchemy showed me some old symbols that show how kissing-cousin silver and the moon once were . . . but there’s never any direct lines of influence, there’s never any absolutely clear origin stories, and I can’t read Latin. If I were Peter Falk, I could figure this out in fifty-two minutes. I’m just me, though: got a handful of facts, but they keep slipping through my fingers.

The character Darren is a bad-ass, truck-driving, liquor-store-robbing, cop-killing dude. But you make his favorite drink strawberry wine coolers, which is pretty girly. Can you explain what led you to that as opposed to, say, whiskey or malt liquor?

At the most basic level, it’s probably just that I don’t like whiskey or malt liquor—beer either—but I knew Darren was going to be chugging his drink of choice. So, not wanting to gag every time Darren waltzed on-page, I picked something that went down easy. Really, though, one of my stepdads, he was a truck driver sometimes, and I’d go with him on a run every now and again, and he would always drink strawberry wine coolers the whole way. And this was a guy who was constantly in fights. But he drank those strawberry wine coolers, and he’d glare over the top of the bottle at anybody looking askance at this. What he said was they were good because they didn’t really make him drunk. I never tried one, but I’d get to smell them sometimes. I still miss that smell.

The narrator of Mongrels is never given a name. Why did you choose to do that?

I should come up with a better answer than the real one. Which is that I just never thought of it, at least not until it was too late. Isn’t that what James Welch said about Winter in the Blood? Anyway, this is always the trick with first-person, of course. A narrator saying his or her own name, that’s on the spectrum of them looking in the mirror and talking about their eyebrows and cheekbones and lips and all that. But, yeah, other people might, like, say it every now and again, right? That’s usually how you hear it, in first-person. Just, in Mongrels, they were always changing names, right? So what I figured, finally, was that his real name is secret, it’s a power for him, so he’s not going to just give it away. Everything else, sure. But not that. Not yet.

As for my model for this, my precedent, should I need one, I’d probably try to fall back on Stephen Wright’s Going Native, if I could. It’s been a few years since I read it, but I think that it’s a lot like Melville’s The Confidence Man, where each chapter, the identity of the main character gets buried deeper and deeper, until you start wondering whether you really know anybody at all. That’s how Lost Highway-choose to remember Going Native, anyway. And there’s some name-shuffling that goes in with Stencil in Pynchon’s V., yes? I really imprinted on that book, once upon a time.

None of which are real answers, I know. Always trying to hide behind books, I am. And Yoda-speak.

Really, though? I halfway suspect that the reason this narrator doesn’t have a name is that one of my 2012 novels, Growing Up Dead in Texas, it already has a narrator named “Stephen Graham Jones.” Didn’t think I could away with that twice.

I’ve always considered the werewolf myth a metaphor for our Dionysian inner nature. That we carry a beast within ourselves and, under the right circumstances, it can be released with a terrible and animal-like fury. I felt the same philosophy at work in your novel. Do you feel that way? And what else do you feel the werewolf represents in literature?

Yeah, that’s pretty much what I suspect, too. Also, note that, back in the fifteen and sixteenth centuries, when that “inner nature” expressed as cannibalism and murder—which mass hunger and just rampant inequity often led to—instead of owning these bad deeds, the perpetrators tended to always claim that they were werewolves, and, c’mon, y’all, this is just what werewolves do. But, yes, they said this under significant duress applied by the Inquisition. Still, when you read some of those old accounts? There’s an exuberance to these werewolf confessions that seems to indicate that claiming or blaming werewolfism was both a way of denying guilt (which is maybe preserving the soul?), and of asking to please let’s now skip the rest of this torture session, and get right to the beheading, yes? Once you claim to be a werewolf, I mean, what more is there to wring from you? Line up for the wheel, and don’t crowd the werewolf or witch in front of you.

What actors would you like to see play the roles of Darren and Libby?

Someone in Birdland suggested Sawyer from Lost for Darren. Josh Holloway. Libby . . . hard call. I keep coming back to Sarah Wayne Callies. Probably because I liked her accent for The Walking Dead. And, talking accents, diction? The narrator in here, his voice is pretty much exactly Tye Sheridan’s, from Mud.

Your novel seemed to imply that lycanthropy is both a curse and a blessing. Do you see being a werewolf more as a punishment, like lycacon who was turned into a wolf by Zeus, or a gift of nature?

Yeah, that’s the crux. Do we side with Darren, or do we side with Libby? Which is the position the narrator is in for Mongrels, just the whole way through. His heart goes one way, his head another.

Why did you choose the horror genre as a means of expressing yourself as a writer?

Man, hasn’t even been voluntary, really. I mean, I would have volunteered, would have been first in line. But, really, that’s just where my head is—horror. It’s how I’m wired. I try to do other things, but the dark stuff always rises, the further I get into the story, until the words are just scumming the top of a pool of blood, and I think, Whelp, here I am again. Guess I better start swimming.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.