The term ‘Flanderisation’ is, in fandom circles, a relatively well-known one – it refers to sitcom characters’ personalities being, as the years roll by, wholly consumed by one specific trait to the exclusion of all others. It draws its name from Simpsons character Ned Flanders, who began essentially as patriarch of the ‘Joneses’ who the Simpsons would perennially try and keep up with, and who was mildly religious but mainly as part and parcel of his upstanding moral character.

Fast forward a few years, and Ned became an unapologetic religious zealot, wide of eye and frothy of mouth, desperate to purge the world of sin. The same process took place with Homer Simpson himself, who was originally a slothful and at times callous working-class man – the antithesis of the archetypical teevee dad – only to later become what fans dubbed ‘Jerkass Homer’, or what the show itself called ‘Captain Wacky’.

Flanderisation, though, is not quite the right word for what happened to Homer’s boss and sometime antagonist Monty Burns. He was originally the closest thing Springfield really had to a villain, coming off like a socialist-realist caricature of a factory owner, blasé with his workers’ well-being and mainly concerned with profit, even boasting his own ominous bad-guy theme (or occasionally Star Wars’ Imperial March). Then – at about the same time Flanders became a Bible-thumper and Homer started pulling off fake kidnappings – Burns degraded into a pathetic figure, helplessly out of water in the modern world and verging on senile, without even the belly-fire of the town’s other elderly residents like Grandpa Simpson.

There was barely even the seed of this in Burns as originally conceived – he was always old, and certainly physically frail, but beyond that he was calculating and competent, ruling over the nuclear power plant with an iron fist and happy to dabble in other pursuits like baseball and politics, both of which he approached in a wonderfully corrupt way.

Perhaps the first hint of the doddering latter-day Burns came in ‘$pringfield’, where – channelling Howard Hughes – Burns cloistered himself off in the penthouse suite of his casino, became obsessed with microscopic germs, and designed and built his own cutting-edge aircraft, the Spruce Moose (‘Hop in!’). The latter revealed the antiquated mindset that became the core of doddering Burns – he illustrates the Spruce Moose’s capabilities with a hypothetical seventeen-minute journey between New York’s non-extant Idlewild Airport and the Belgian Congo. There would follow other anachronistic gags, from trying to send a letter to Siam by autogyro, to mistaking the Ramones for the Rolling Stones and ordering their murder, and – in possibly the nadir of this – turning up to a gas station in his 1906 maroon Stutz Bearcat dressed in Edwardian driving cape and goggles, mistaking Marge for the attendant and demanding she re-vulcanise his tyres. Fairly harmless, throwaway stuff, but indicative of the birth of a very different Burns, a Burns who couldn’t dominate board meetings or engage in usury as a hobby, a Burns who didn’t write his own florid autobiography after a minor health scare, a Burns who could barely be left unattended.

‘The Old Man and the Lisa’ is a particularly good illustration of doddering Burns. Having gone broke and lost the power plant, due mainly to more he’s-so-old gags (‘Smithers, why didn’t you tell me about this (1929) market crash?’), Burns must try and make it as an everyman, and the results are depressing. He breaks Smithers’ crockery trying to clear it away, and, before long, is committed due to his confusion over the subtle distinction between ketchup and catsup. It is only Lisa’s intervention that sets him back on the road to being an evil tycoon – she demonstrates how animals can become trapped in plastic six-pack holders, knowledge he uses to create a thriving fishing industry – but this is really the final few minutes getting things back to the status quo, and, to be honest, isn’t so very evil, certainly not compared to the Burns who roared with laughter at the memory of ‘that crippled Irishman’.

One particularly telling moment comes when Burns rides a bus, and Barney greets him with ‘aren’t you that guy everybody hates?’, to which he responds ‘oh my, no – I’m Monty Burns’. Ironic? More like oddly true against this backdrop. Doddering Burns is so inoffensive he becomes a target of pity rather than hate. The episode does at least feature classically evil Burns in an early segment – ‘Family, religion, friendship. These are the three demons you must slay if you wish to succeed in business. When opportunity knocks, you don’t want to be driving to a maternity hospital or sitting in some phony-baloney church. Or synagogue’ – but this does little to make up for his characterisation in the rest of the episode. Some of his fish-out-of-water stuff hits home, such as imploring the hippy at the recycling centre to ‘Shine on, you crazy diamond!’, but ultimately he even seems a little confused at how the omni-net could be considered evil. Classic Burns would be revelling in the deaths of all those sea creatures (‘That mouse butchered that cat like a hog!…is all TV this wonderful?’).

The real turning point seems to come in ‘Homer the Smithers’. From the off, it depicts Burns as unnecessarily reliant on his assistant, to the point of personal helplessness. Eventually Homer, snapping from the constant abuse, punches Burns. Burns’s reaction – the same man who, only five years earlier, had ordered Homer beaten to a pulp over an insulting letter – is to curl up and hide in blind fear.

Too terrified to seek Homer’s further assistance, Burns attempts to become self-reliant, learning to operate a telephone, brewing his own coffee with no little mess, and recklessly chauffeuring himself home in the evening – even though, back in ‘Two Cars in Every Garage and Three Eyes on Every Fish’, he had driven himself perfectly ably while drunk. Ultimately – because status quo – he is knocked out of a window and returns to being completely reliant on Smithers. But his helplessness shines through throughout, both when Homer strikes him, and during the Homer-Smithers fistfight at the end, which he haplessly attempts to break up by bursting a paper bag – presumably he no longer has his hired goons on retainer.

From this point on (‘The Old Man and the Lisa’ comes chronologically after this) he would descend further and further from tyrannical businessman and toward doddering old fool. The horrible conclusion? That either Homer striking him, or his fall from the window, knocked something loose in his brain and triggered the onset of senility – which lends a dark edge to the running joke of his never remembering Homer’s name. There is a similar plotline in The Sopranos, where Tony’s uncle, Junior Soprano – who already cut a Burns-ish figure – is feigning senility to beat trial, over the course of which he takes a fall on the courtroom steps, after which it becomes increasingly unclear how much of his dementia is an act.

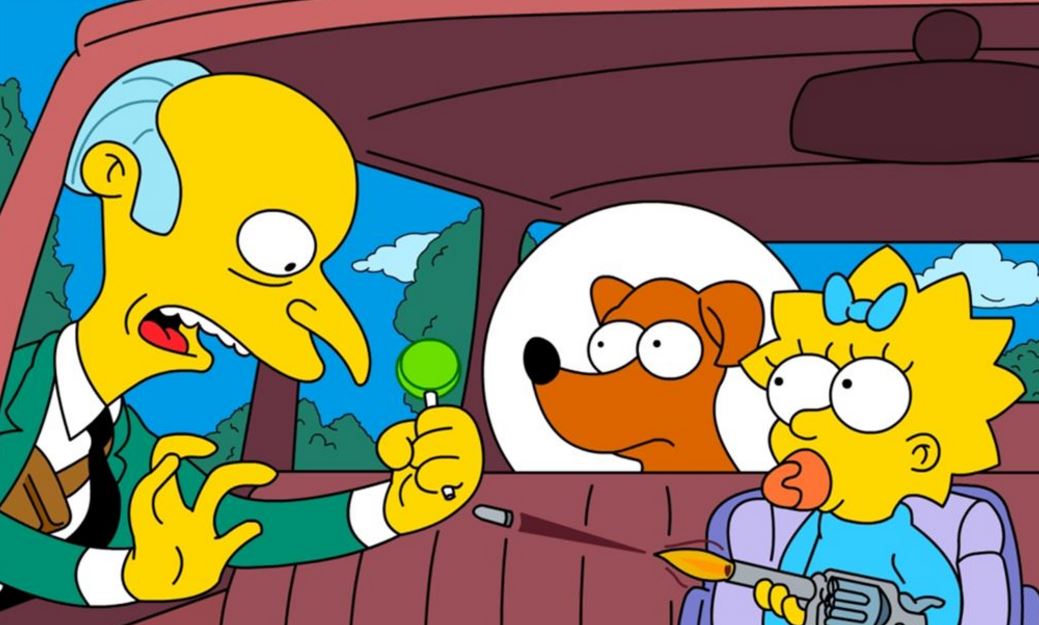

The bitter irony is that this is hardly the worst injury he would suffer on the show – not even the worst injury he would ever suffer at the hands of a Simpson. His abortive attempt to adopt Bart ended with being dropped down his own trapdoor-trap (‘Sir, try to land on Leonard’s carcass!’), but the most obvious example is of course the time Maggie shot him. This was the shaggy-dog ending to one of Burns’s quintessential acts of villainy, blocking out the sun with a vast metal disc to force people to use electric lighting full-time (Maggie herself was provoked more by his literal attempt to take candy from a baby). Being shot in the chest at point-blank range, rendered comatose, and pronounced dead before being transferred to a better hospital scarcely slowed down Burns’s villainy and air of cold command – upon his revival, and having revealed it was Maggie who shot him, he immediately demands ‘Officer, arrest the baby!’

One might argue that the latter-day Burns was a misfired attempt to soften and humanise the character (much as Moe was transmogrified from surly loanshark to suicidal depressive). But the fact is, Burns had already had the occasional moment of humanity – even as early as season one, he was showing enough vulnerability to ask Homer for dating advice. Season two saw Marge painting him nude to emphasise his physical decrepitude (‘I know what I hate. And I don’t hate this’), and his admission to Homer that he too knows the sting of male pattern baldness. The crucial point is that none of this had to detract from him running the power plant like a feudal fiefdom, dumping nuclear waste in the park, or even setting up his own cult and trying to have people worship him as a god (which ends embarrassingly when he catches alight, but this is more him succumbing to his own hubris).

Sadly, the general consensus is that – like Burns himself – The Simpsons as a whole is a mere shadow of what it once was, with most commentators putting the tipping point at about the time of ‘The Principle and the Pauper’, in which Principal Skinner was revealed to have been an impostor all along. The decline was not just limited to the destruction of established characters, though – even the most casual viewer will notice a far greater reliance in pointless celebrity appearances, clunky references to not-so-recent pop culture, and stretching single jokes out for far longer than needed. It still has its moments, nobody can deny that. But it’s no longer the laugh-a-minute cultural juggernaut that defined a decade, and could go from smutty to heartwarming with a deftness that spawned a legion of imitators but has never quite been topped.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.