Westworld is a show about robots with magic powers who look like beautiful women getting into fights, and so is by nature absurdly self-indulgent – and that’s before we even touch on it burbling on about philosophy. So off the bat, one must give the third season credit for, despite everything, actually reining in the self-indulgence a bit by going with a largely standard chronology, rather than constantly dropping in flash-backs, flash-forwards, and God help us what would probably turn out to be flash-sidewayses and flash-u-turns if you actually puzzle it all through on paper.

This approach worked in the first season, because the non-linear timeframe was the twist. But when the writers carried this on to the second without the same reasoning, it became – how to phrase this without using the epithet ‘wanky’? – one of those intentionally over-complicated works that hopes to appear deep merely by being confusing. So, as welcome as the third’s A-to-B time progression is, it also makes clear just how much of the show is flash over substance.

The bitter irony of this is that Westworld’s narrative has always strongly rejected that idea – the hosts are explicitly not just flash, they’re such good simulations of human beings that there’s no real difference. In blunt and brutal terms, they have a soul. Now, it would be a little too poetic to accuse the show of not having a soul at this point. There’s clearly one rattling around in there, but nowadays it seems to be more interested in loud noises and bright lights than questions about the nature of existence.

The only question of that sort here is ‘where does this exist, anyway?’ Westworld has always had trouble with geography. It originally presented a park of indeterminate size, built above and around a maintenance area of the same indeterminate size which was somehow child’s play to navigate, and then it turned out there were other parks as well. So now that they’ve gone skipping idly here and there around the real world, it doesn’t, really, make a huge amount of difference. The locales can be as different as chalk and cheese, but the characters will spring instantaneously over from one to another when they need to.

Suddenly setting it in the outside world (as opposed to the very occasional bit or piece season 2 gave us) has abruptly transformed Westworld from a story about a Western world into one about a cyberpunky, not-too-distant future. Unfortunately, a lot of the work of actually building this world is done through some aggravated telling-not-showing, and that kind of thing wears quickly without Anthony Hopkins reading it out.

The most distressing part about this is that when they do show, rather than, tell, it can be very effective. Squint at some of the computer screens you see, and you get the suitably dystopian touch that the algorithms are deciding who can and can’t breed. One of the best of these initially comes off as a glaring misstep: when the show’s depicting what is supposedly mass chaos, it’s initially little more than the crowds no longer all marching along like army ants late for an important meeting, even daring to – gasp – sit down.

But these light touches are few and far between, and far more often things get loudly exposited to the audience instead. And what’s so damning about this is that it betrays an alarming lack of trust in the audience – the same audience, mind you, who had the show’s writing staff biting through their keyboards because they kept working out the twists ahead of time.

The remedy they came up with seems to have been to take out the twists, or at least, not rely on them to carry any real importance. The few still present are just retroactively doing the work of developing the characters – whoops, it turns out Mr. (x) is actually a bit (y). Hooray, or possibly boo. There’s nothing here that poses any risk of pulling the rug out from under the viewer like the old days.

It’s surprisingly rare that this season of Westworld gives its major players a chance to actually emote, or interact, or do much beyond growl meaningful-sounding gibberish at each other. New acquisition Aaron Paul is a particular victim of this, too often reduced to being Evan Rachel Wood’s mugging, mouth-gaping sidekick. And with this side of things being let down, very often the show finds itself flailing to drum up pathos for characters who, realistically, you will not be remotely invested in.

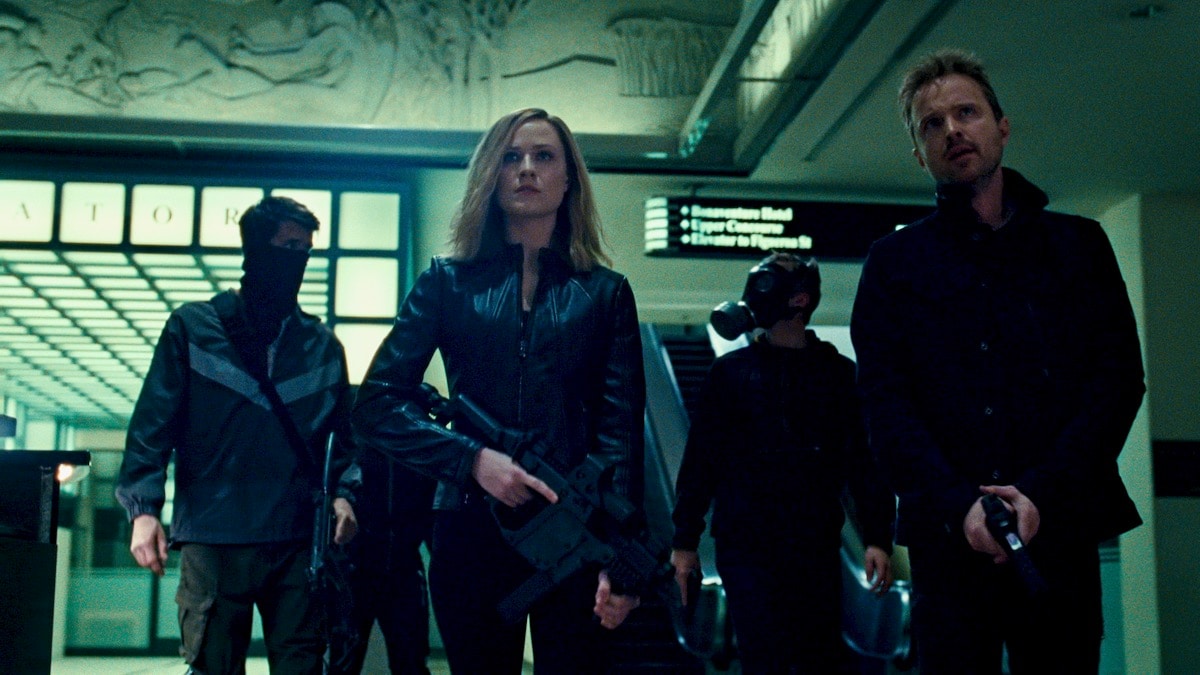

So, the substance is paper-thin and feather-light – but what about the flash? Yes, there’s lots of scenes of attractive women walking around in tight black outfits, holding guns, spouting off techno-fiction that would bring a tear of pride to Star Trek’s beady little eye. In fact, if you were to boil this season down to only those scenes, I can’t think you’d lose very much runtime.

As such, and having established nobody’s watching this for the plot, when those attractive women get into a fight it had better be something bloody special. Unfortunately it’s not, despite the shamelessly adolescent inclusion of katanas and robots. These scenes, which should be so pivotal by the process of elimination, can’t help but feel rote and unmotivated. There are no real stakes to them, as you might expect in a show where death is only as permanent as making another robot out of milk – but neither do they then become a fun, jolly thing.

Speaking of fights being a fun thing, though, there’s one particular shot that’s drawn so blatantly from Fight Club that it’s genuinely surprising nobody sued. By and large, though, the creative debt is owed to The Matrix – simulated reality, artificial intelligences, robots, kung fu, I could keep going and after watching for five minutes you could too. The Wachowskis, who owe their own debts to East Asian cinema (also reflected here), probably wouldn’t complain. They don’t need to. There is always a risk, in nodding to another work, that your audience will think ‘gosh, that was good, I’d like to watch that instead’, and this season of Westworld is definitely running that risk.

As a final thought, I really have to counsel any work which already has so many similarities to The Matrix against introducing a French villain. Take this season of Westworld as a warning. They must have said his name, they must have, yet for the life of me I was physically unable to think of him as anything other than the Merovingian, yammering on about wiping his arse with silk and just generally being conspicuously French.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.