Famously, all the best Die Hard sequels were never in fact intended as Die Hard installments, beginning life as unrelated action spec scripts which later had Bruce Willis’s John McClane grafted onto them surgically. It was only at about the fourth or fifth Die Hard that they began being written as such, and – by some wild coincidence – about then that the franchise degenerated into cookie-cutter summer action blockbusters. If there’s a lesson to be taken from this, other than ‘don’t make Willis’s hairpiece an executive producer’, it’s that a good sequel doesn’t need to be intended as such.

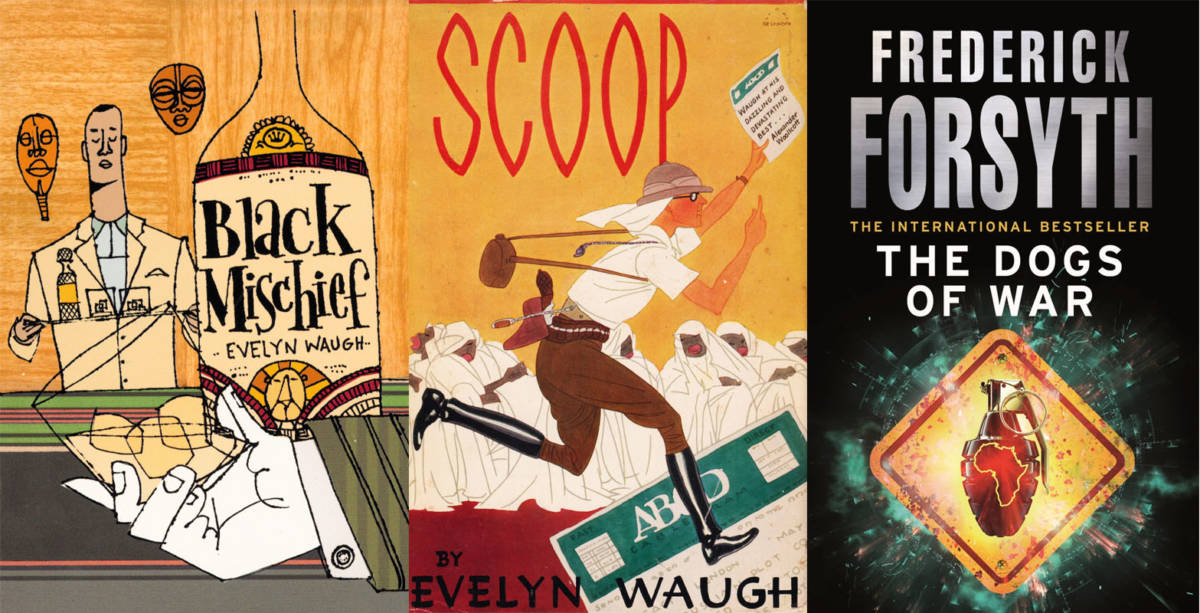

Which brings me neatly onto a literary trilogy that never was: Evelyn Waugh’s Black Mischief and Scoop, and Frederick Forsyth’s The Dogs Of War. Waugh is primarily known for inter-war comedies involving posh boys blundering through farces – and, later, for his Catholic-themed gay romance ‘Brideshead Revisited’. Forsyth, meanwhile, wrote a whole series of hard-boiled international intrigues, but his most popular work by far is Day Of The Jackal, in which French ultranationalists hire some sort of evil James Bond to take down Charles du Gaulle.

Black Mischief, Scoop, and The Dogs Of War all fit quite neatly into their respective authors’ modus operandi. Black Mischief and Scoop see posh boys ending up in tinpot African dictatorships and screwing with affairs of state almost by accident. The Dogs Of War, meanwhile, has an ultra-rich London financier discover that an African nation is harbouring an untapped mountain of platinum, and setting up a friendly coup so his firm can best take advantage of this. (This plot may sound familiar, since it inspired Mark Thatcher, son of the former British Prime Minister, to have a go at arranging a friendly coup himself.)

The common thread is probably already becoming clear – these are stories of Europeans going to Africa, and doing what Europeans tend to do to Africa (while it’s a fanciful description, it rhymes with ‘cape’). Waugh’s entries take place during the waning days of full-on colonialism, while Forsyth’s takes place after colonialism was ostensibly over, but really, little enough has changed. As such, both have moments of racism we simply can’t recreate with modern technology, and Waugh is clearly the greater offender in this category. Forsyth makes some fairly unpleasant generalisations about European and African soldiers, noting that only the Europeans tend to keep their eyes open while firing, but would never have a sympathetic character employ the phrase ‘you black booby’ – certainly not with the relish Waugh uses it. Indeed, Forsyth is the only one of the two authors to depict black people as anything other than unsympathetic, dim, or both.

Both Black Mischief and Scoop are drawn heavily from Waugh’s experience as a foreign correspondent in Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) – with Scoop, in particular, casting a wry eye on journalism as a trade, casually describing the processes of submitting fraudulent expense sheets and outright fabricating headlines, and featuring a press baron who makes Rupert Murdoch look like Rupert Bear. Black Mischief, meanwhile, deals with the tension between modernity and undeveloped nations – or rather, nations which have been developed just enough for European powers to extract value from them. This is exemplified through the contrast between Emperor Seth, an Oxford graduate who could pass for one of today’s well-meaning liberals, and the head of his army, General Connolly, a veteran of colonialism who, even as an Irishman, understands African tribal warfare a good deal better than Seth himself.

Seth is desperate to modernise his fledgling country in any way possible and doesn’t really care how much sense his methods make. He starts off fairly small, by bringing a primitive tank over to his tropical country (Connolly duly uses it as a punishment cell) and encouraging the use of contraception in a culture where fecundity is an important virtue – then ultimately reaches the nadir of this when he starts printing his own currency, backed by precisely zippo. You may remember that Zimbabwe tried this in recent history, and it didn’t go well for them.

Most of these are due to the influence of the protagonist, Basil Seal, who Seth remembers from Oxford as the big man on campus. They say the protagonists of first novels are the author as either Christ or Satan, and while this was by no means Waugh’s first book, Basil does at times feel uncomfortably like Waugh indulging his nasty side in fiction. Installed as Minister for Modernisation, Basil almost immediately alienates Connolly, mainly for feeling slighted, choosing instead to side with a local con-man who feels so much like an anti-semitic caricature it’s sometimes a shock to see him described as an Armenian.

There is one exchange in which Waugh lets the mask slip a little, and makes it clear there are parts of modernity he likes and parts he doesn’t like – leaning more towards principles rather than gadgets:

‘…we’ve got a much easier job now than we should have had fifty years ago. If we’d had to modernize a country then it would have meant constitutional monarchy, bi-cameral legislature, proportional representation, women’s suffrage, independent judicature, freedom of the Press, referendums…’

‘What is all that?’ asked the Emperor.

‘Just a few ideas that have ceased to be modern.’

(Black Mischief)

Subtle stuff, eh? It’s particularly interesting that Waugh, usually an arch-conservative to rival the Pope, saw women’s suffrage as a positive development left by the wayside by the more popular sort of modernity – particularly as Waugh’s relationships with women were often fraught, and, after his first wife cheated on him, irrevocably coloured by that experience.

Ultimately, Seth is ousted by a French-backed coalition, who attempt to install his infirm, exiled and demented uncle in his place – only for the man to die, and for Azania, lacking any heir, to end up taken over by the League of Nations by default. Which seems particularly mean-spirited, given that Abyssinia was the only African country to successfully resist European colonisation (at least, until Mussolini turned up). Basil receives little comeuppance for his role in this mess, beyond the nature of his character being revealed as predatory and red-toothed when he joins some of Seth’s tribesmen for what turns out to be a cannibal feast.

By contrast, Scoop’s protagonist, William Boot, is a wide-eyed naif who wants nothing more than to stay in his country house writing his flowery nature column for The Daily Beast. Because the gods are cruel, he is promptly mistaken for another Boot and called up first to London (an awful enough experience in itself) and then to cover the civil war in Ishmaelia. Given the 1930s setting, the civil war is between communist and fascist factions, leading to a morbidly hilarious Spy-vs-Spy-esque section when Salter, the foreign editor, explains exactly how to tell the difference:

‘…the Fascists won’t be called Black because of their racial pride, so they are called White after the White Russians. And the Bolshevists want to be called Black because of their racial pride. So when you say Black you mean Red, and when you mean Red you say White, and when the party who call themselves Blacks say Traitors they mean what we call Blacks, but what we mean when we say Traitors I really couldn’t tell you.’

(Scoop)

As both sides have their own embassy, William ends up needing to obtain two passports to actually make the trip over there – just one in a series of moral lapses and casual crimes that his bosses at the Beast don’t even blink at, and in fact actively encourage throughout so long as they can file a byline a second sooner.

For all Waugh’s racism, the antagonist, Dr Benito, who heads up the Ishmaelian communist faction, is a surprisingly rounded character, intelligent, sophisticated, and only pegged as a villain by William because he very obviously isn’t a good egg. (Waugh’s racism actually turns out to be a strength here, with Benito’s internalised racism coming across very effectively.) Yet neither he, nor communism as a whole (and Waugh hated that to the point of being worryingly fond of fascism), are the true villain of the piece, since that can only be the press as an institution – and it is the press that Waugh’s ire is primarily aimed at.

Waugh creates a truly disgusting portrait of the international press corps, describing Scoop’s central group as having ‘loitered together of old on many a doorstep and forced an entry into many a stricken home’. This is in the glory days of yellow journalism, when, sans real news, the press would simply fabricate some – illustrated by a particularly dark story of a reporter who, sent off to cover a war in the Balkans, got off his train in the wrong country and cabled off a lurid story of gritty street-fighting, leading to a drop in stock prices, public panic, and, yes, ultimately a war all of his own making.

Through a similar series of happy accidents, William stumbles into the discoveries that there’s a Russian spy creeping around, that the President has been taken prisoner by Dr Benito’s faction (the ‘scoop’ of the title), and, ultimately, that Ishmaelia has significant natural deposits of gold – which explains the great European powers clashing there by proxy. This is in contrast to the rest of the press corps, who are happy enough dashing off wild fantasies, swallowing whole every press release Dr. Benito gives them, and letting him point them towards some unspecified excitement off in the country’s interior – that is to say, away from the capital and the coup.

Before returning to a hero’s welcome as ‘Boot of the Beast’, William also ends up swept into the counter-revolution – which consists of a British investor pointing a big, angry, drunken Swedish consul in the direction of Dr. Benito and his cronies, and letting nature take its course. While this is intended as comedy verging on slapstick – as, indeed, are most of the Swede’s scenes – it comes over worryingly like the kind of mighty-whitey material that would make Rudyard Kipling blush and Herge give up the day job. Chairman Mao’s maxim was that ‘political power grows out of the barrel of a gun’, and he might well have appended ‘because then you can’t be bludgeoned to death by any big dude who cares to do so’.

While there are scenes in both books in which Africans get the better of Europeans, these are few and far between – and, crucially, all take place offscreen (as it were). In the case of Black Mischief’s Prudence being stewed, this was necessary to preserve the reveal. Scoop relates how many missionaries and would-be colonists met a similar fate in Ishmaelia, and how the bulk of the press corps fall foul of the town’s night guard when trying to make an early start and beat the other guys to the story. But there is no vice-versa’d equivalent of Scoop’s Swede tearing through the Young Ishmaelite faction, or, in Black Mischief, a hefty Canadian priest casually abusing a combat veteran.

This is, of course, what one would expect from a colonially-minded author – the white man depicted as superior, only fallible when off the maps and deep in the heart of darkness – and no less from an honest depiction of colonialism as a practice, where whites abusing blacks was de rigeur, whereas blacks abusing whites would most likely lose a hand at best.

To Waugh’s credit, he doesn’t depict Africans as uniformly savage – Seth’s problem, if anything, is that he’s too civilised. Both Black Mischief and Scoop give potted histories of the (fictional nations) in which they take place, with Azania leaning heavily on Abyssinia’s then-recent history, while Ishmaelia seems to draw more from the tragic tale of Liberia – set up as an independent country for freed American slaves, who upon their arrival immediately enslaved the locals. However, all the real power almost invariably rests with Europeans and European interests – particularly in Black Mischief, where Seth’s goose is cooked the moment he drives away General Connolly and the French Ambassador.

Forsyth’s The Dogs Of War is immediately different in tone – for one thing, it’s a thriller rather than a comedy, yet there are some similarities in the way they depict the grittier parts of life, and in so doing strike a very fine balance between the plausible and the nigh-on farcical. Sir James Manson, the financier behind the plot, is a bit too flat and straightforwardly atavistic for a Waugh novel, but his slimy fixer Endean would fit in just fine. Lead mercenary Cat Shannon, on the other hand, is edging in the direction of James Bond, particularly when he schtupps Manson’s awful daughter and figures out exactly why Manson’s arranging a coup.

As in Forsyth’s more famous The Day Of The Jackal, the plot is a slow-burner, depicting in depth the meticulous preparations involved in bringing about the violent climax, in this case toppling a small West African nation – indeed, there’s one section where Cat and his mercenary pals have to secure fraudulent passports, which Forsyth glosses over by telling the reader that a full account of how to do this can be found in The Day Of The Jackal. Phony passports, however, are possibly the most innocuous part of their preparation – and Forsyth goes into lavish detail in showing the tricks major arms companies use to ‘lose’ enough ammunition and ordnance to supply a mercenary outfit.

To reference James Bond again, just as Ian Fleming was drawing heavily on his own experience with MI6 in his novels, so too did Forsyth – particularly with The Dogs Of War, as he cut his teeth as a spy while covering the Nigerian Civil War as a freelance reporter (disgusted by the way the BBC refused to cover what he saw as a ‘particularly British cock-up’). So when he talks about the dirty tricks that fuel the mercenary trade, he’s not pulling it out of thin air.

Most of the preparations take place in Europe – and, as a result, so does most of the narrative. There is a prologue introducing us to the mercenaries as they flee after working for the losing side in the Nigerian civil war, and Cat takes a brief trip over to Zangaro to test the waters, over the course of which he kills a palace guard, hides the body, and gets away scot-free. These, however, are the only times in which any major characters even see Africa before the third and shortest section of the book, which follows the coup itself.

As geopolitics had only changed so much since Waugh’s day, the Soviets are quick to try and get their oars as well. Kimba, the Zangaran dictator, is communist-leaning anyway, but once Moscow learns about the mountain of platinum (thanks to one of Manson’s untrustworthy research guys) they send a KGB guy to make sure he remembers his patron.

Finally, after collecting any number of illegal arms – and scaring off a jealous rival mercenary – and the gang set off to Zangaro, stopping only briefly along the way to pick up some pals from Sierra Leone, more mercenaries and the mysterious Dr Okoye. The coup, having been extensively planned, goes off as well as one might expect – two of Cat’s guys die, but they successfully storm the palace, killing Kimba and his KGB buddy.

Endean shows up not long later, having recruited an East End gangster as his travelling bodyguard. In a Waugh production, the latter would probably pull off the coup himself. Instead, he’s shot pretty much instantly by Cat – as is Manson’s prospective candidate to lead Zangaro, Colonel Bobi. This is the turn – to Endean’s horror, it turns out that Cat, who’s spent a good chunk of his life in Africa working shoulder to shoulder with African people, isn’t particularly invested in making a pile of cash for Manson. Rather than pulling off the coup for Manson, the mercenaries have been doing it on behalf of their old pal ‘the General’ (a barely-veiled General Ojukwu of Biafra).

So, Endean gets sent packing, and Manson has to pay a fair market price for his platinum like a sucker. Meanwhile, the mercenaries install Dr Okoye as the new Zangaran President, with the country’s formerly disenfranchised immigrant workforce forming the bulk of his army. This is perhaps a fairly clean-cut, whitewashed idea of the aftermath of a coup, but then you could assume that the General knows his stuff. Their job done, the mercenaries go their separate ways – with their Corsican knife-man refusing payment and going off to help the Hutu in Burundi – and with Cat himself sending his payment to his dead friends’ families, then revealing that he’s had terminal cancer the whole time and topping himself.

Both Cat and the Coriscan’s actions in the epilogue, and the climactic twist, are the fruition of the book’s recurring idea that despite being guns for hire – or dogs of war, you might say – mercenaries have a moral code, even if it is an unfamiliar one. And, indeed, that they feel more at home in Africa than they do in Europe, a sentiment echoed by the prospector who finds the platinum in the first place. More importantly, though, despite not getting the spotlight (because they’re not sexy, exciting mercenaries) Dr. Okoye and the General are as important (if not more so) as actors in the plot as Cat and the gang are.

Bluntly, Waugh would have hated this – or, just as likely would have been unable to conceive of such a thing. None of his African characters display any agency of their own – even of his African elites, Seth is trying lamely to live up to his role as heir, a role in which he is easily manipulated by Basil, and Dr. Benito is a catspaw for the Soviets.

(In Black Mischief, ironically, it is Connolly’s native wife, only ever named as ‘Black Bitch’, who comes closest to having any agency, serving as a bit of a wildcard and very nearly defusing the coup against Seth.)

So in a very real sense, this is the other shoe finally dropping. After years (or, in this trilogy setup, two books’ worth) of colonialism, of coups that are proxy power struggles between European interests, of the Basils and Mansons of the world wandering up and pillaging African nations, finally the world’s power-brokers are rudely reminded that the Africans are there too, that they have agency of their own, and aren’t best pleased by the rubber plantations and unequal treaties. Perhaps it’s iffy that they only become capable of it with help from Cat and crew, but it’s a marked improvement on how Waugh treated them.

One wonders exactly what Okoye’s Zangaro might make of Azania and Ishmaelia – which presumably are nearby neighbours in the same fictional region of Africa. The latter two, after all, suffered coups that were far less smooth processes, with the formerly independent Azania becoming an Anglo-French protectorate, and Ishmaelia falling subtly but definitively into the British sphere of influence. Given the destruction of most of their civil institutions (Ishmaelia’s were corrupt to the core even before Benito’s purges, and Azania’s ended up centralised under Basil) both likely ended up destabilised in much the same way as Iraq did after the US invaded it in 2003 and summarily dismissed the entire civil service.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.