Ah, Tom Hiddleston, how I have loved thee from afar all my life. Well, not all my life, just from the first Thor movie. From that first moment I saw Loki’s villainous visage, I was a goner. However, it isn’t my love for Hiddleston that has me so enraptured by this production (though that is a factor) of Coriolanus, it is the minimalist set, the contemporary costumes despite the Shakespearean dialogue, and the wonderful performances by everyone involved.

Coriolanus isn’t one of Shakespeare’s famous plays. His political plays have never gained as much traction as his tragedies, and even among the political ones, people mostly remember King Richard III. I studied Coriolanus back in university, and while I remember it, it certainly didn’t make the impact it has on me now.

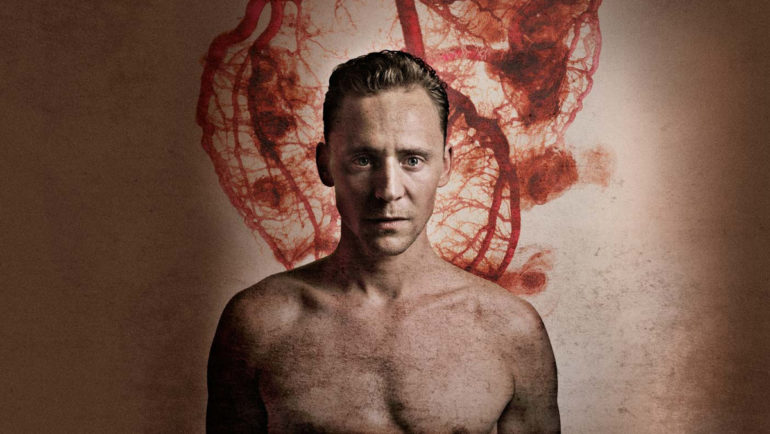

The production relies on a very minimalist set, a small square of space, with chairs, ladders, bodies and other props evoking the space we are supposed to be in. They create a space of war with a ladder, sound effects, and an immersive sword fight between Hiddleston’s Caius Marcius and Hadley Fraser’s Tullus Aufidius; daughter-in-law and mother-in-law sewing together immediately evokes the home space – this production is proof that you don’t need an elaborate set to stage a Shakespearean play, even one about war. We still get the theatrics of war, like after Marcius’ ravaging of the Volscian army, Hiddleston emerges with blood dripping down his face and we are forced to witness his wounds as he strips and waters pours down from above him – we see the toll war wreaks on a man.

Despite his contributions to Rome, the citizens of Rome are angry that he doesn’t seem to want to do what they need him to, feeling that he makes fun of them and doesn’t take their traditions seriously. Marcius reveals his fatal flaw here, for while he is a tremendous general and warrior, he is not adept at politics. He doesn’t know how to speak to the people, his contempt leaking into his tone as he addresses them, and through the instigation of the tribunes Brutus and Sicinius (who are deliciously villainous), he is banished from Rome. Despite the attempts of Menenius Agrippa and Cominius to convince the people to change their minds, the path is set, and Marcius is forced to leave a country that he has loved and defended his whole life, a space which contains the people he has loved his whole life.

A special appreciation needs to be given for Mark Gatiss, who plays Menenius. Gatiss conveys Shakespeare’s dialogue in such a modern and easeful way. While many actors get caught up in yelling his words for dramatic effect, Gatiss makes his gestures, mannerisms count. I was watching the play with subtitles because you can often get lost on the Shakespearean dialogue train, but Gatiss made it easy for me to comprehend. Tom Hiddleston was of course stellar, as per usual. He had to toggle with the emotional poignancy required of his role, as well as channel the ferocious zeal of a warrior, and he did so with aplomb. Hadley Fraser was perhaps the most surprising one of the lot. The last I saw Fraser, he was playing Raoul in Phantom of the Opera, and he is simply unrecognisable in this as Aufidius, the general of the Volscian army.

His relationship with Marcius is a compelling one. Every single time he has met the man on the battlefield he has longed to kill him, yet when Marcius visits his home, Aufidius calls him “thou noble thing” and admits when he sees him that his “rapt heart” dances. There is a spiritual love shared between the two men, because in all the world, they are the ones who truly understand each other due to being in spaces of war. Aufidius allows Marcius to become general in his stead, in order to take revenge on the people of Rome for having banished him. But after a visit from his mother and family, Marcius changes his mind, choosing the route of peace instead of laying siege to Rome like he was supposed to.

Aufidius calls him out for treason and hangs his body in chains, and we actually see Hiddleston’s body hoisted up into the air, dangling from the chains, being gutted in front of us. And on the other side of the stage, we see his mother with flower petals strewn all around her – it is a mother’s triumph and a loss, for she convinced him to save his countrymen, but lost him in the process. Rome’s treatment of Marcius made me think of the way a country treats its soldiers: we want them to fight our wars for us, but when they return to civilian spaces and cannot adapt accordingly, we cast them off and abandon them.

Marcius aka Coriolanus didn’t need to suffer such a fate, and even though it’s his feelings for his mother and family that led to his death, it is a testament that war isn’t the only thing a man breathes. There is a complexity here in how the play portrays the identity of men, that there is more for them than the masculine spaces they are told to inhabit. Coriolanus’ tragedy is the result of him not being what everyone else wanted him to be, to offer sweet words when he does not mean them, to parade his wounds around like some clown at a party. But quite a bit of this comes from hubris and a sense of entitlement, the sense that he does not need to care about the opinions of the citizens because he belongs to a class of men who are born to rule. There is a commentary here about democracy and the state, and Coriolanus’ failure to see that war is not the only thing that defines a country.

This, for me, is the true art and impact of theatre, with National Theatre showing us that you can take a play from the 16th century and make it a relevant viewing for modern day audiences. What a feat, what a triumph.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.