When an email landed in my inbox about an independent comic about people being brought back from the dead with nanobots, I crossed my fingers hoping that this wasn’t taking yet another bite at the depleted, rotting core of the zombie genre. Christian Carnouche’s The Resurrected, fortunately, has cleared that hurdle – and it must be said, technology resurrecting people properly is a far more interesting idea. With the protagonist, Cain, being a member of a special police unit tasked with tracking down the resurrected, it seems like a take on Blade Runner where they don’t even have the advantage of a Voigt-Kampff test. The year is 2037. Cars fly, people come back from the dead, the law struggles to cope, and Aboriginals are still getting a raw deal.

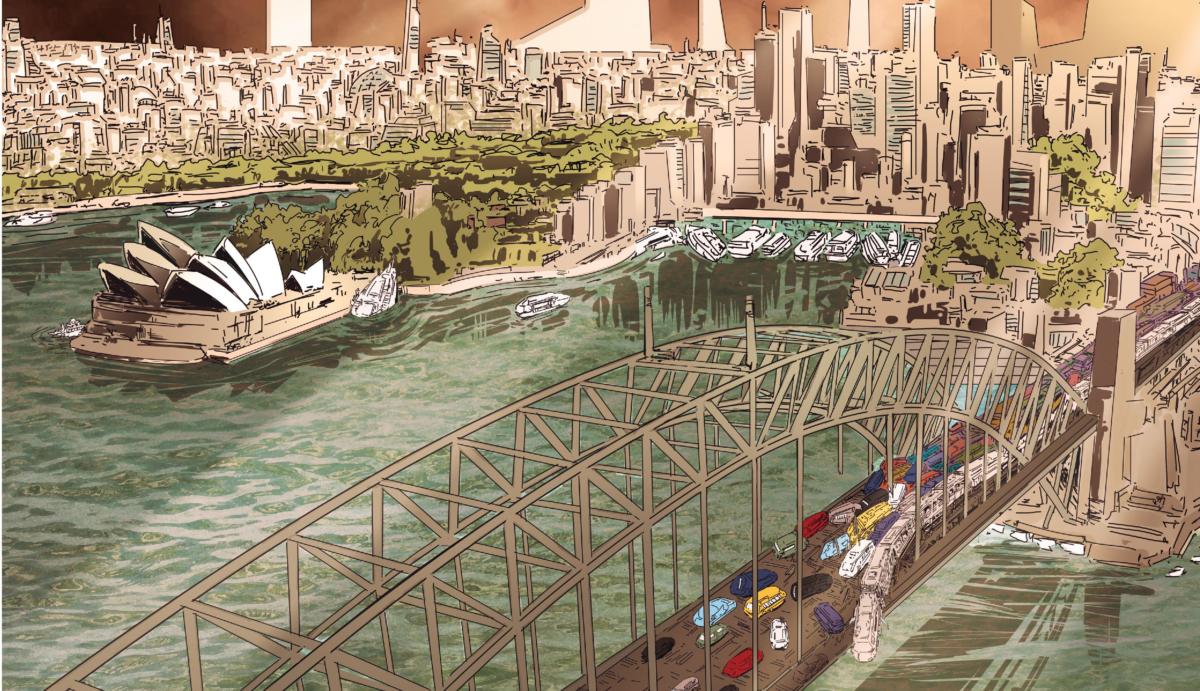

Unfortunately, the first actual ‘rezzie’ we meet has already been re-killed, and the investigation of their tragic story quickly shifts into exploring the protagonist’s own issues – which is all well and good, but come on, guys, you’re burying the lede here. Similarly, the techno-meltdown that brought the world to this state is glossed over for the most part, even though it was this which claimed Cain’s beloved wife and daughter. There’s a fabulous full-page panel of an annihilated Sydney, but that’s as far as it goes – and it’s clearly an aftermath shot.

Perhaps this is the end result of my point earlier that the zombie apocalypse genre has been done to death, and in a wider sense, this solipsistic idea that if the end of days is ever going to happen it’ll be in our lifetimes – that we’ve all seen enough ends of the world in the media that they can be largely taken for granted. This may be so, but a nanobot-themed one is at least a fresh take on it. (Typically the destruction of a major metropolitan centre is wrought by something big, be it Godzilla or a volcano.)

If The Resurrected’s not-too-distant-future, sci-fi setting sounds a little by-the-numbers – and it is, the obviously evil bloke who runs big evil pharmaceutical corporation Drexler literally has the last name Calypse – this is because it’s largely a support system for the main story of how the wider world has impacted on Australia’s Aboriginal population, and how even in the neon-soaked 2030s that power differential still hasn’t gone away.

The strongest part of the two issues released so far is probably the potted history of Australian Aboriginals – which is profoundly brutal even as colonialism goes – dryly listing the benefits of British imperialism while the panels beneath depict the harsh realities, including but far from limited to the Australian government’s policy of abducting Aboriginal children and placing them with white families, a practice which continued until the 1970s. This is by far the strongest section, and could easily have been spun off into an entire comic of its own.

With all this established, the plot has the sense not to simply leave it as backstory. The same dynamics loom large in the aftermath of the techno-meltdown, with the Australian government getting up to all of its old tricks – in a reference to its treatment of that other major marginalised group, immigrants, it holds victims and refugees of the meltdown on its unpopulated Northerly islands in Spartan conditions.

Under the guise of screening for some unspecified infectious disease, these detention centres marked out those of Aborigine heritage – doubtless for no pleasant reason. Among these were Cain’s daughter Yindi, who, in an early revelation, it turns out didn’t die, but – in a bitter twist on the Aboriginal ‘stolen generations’ – was rescued and subsequently fell in with the hulking, quasi-mystic Pem, under whose tutelage she became a ninja assassin and is busily checking off all the suits responsible for the fall of Australia.

It is, evidently, a hell of a thing for Cain to discover that he’s been investigating his own daughter – and introduces the tension that, as a policeman, he has ended up complicit in the same sorts of European-influenced power structures which screwed the Aborigines in the first place, something which Yindi isn’t slow to point out. There’s a certain charm to Cain’s broad, sweary Australian patois (“Fuck me dead!”), but the joke turns sour when it becomes yet another reminder of how his people became second-class citizens in their own land.

As refreshing as it is to see comics address Australian Aboriginals – even simply admitting they exist is rare enough in any media – the lofty ambition of the plot is somewhat let down by the fact that its two disparate arcs don’t quite gel, or at least don’t yet, and over the course of the first two issues seem, more than anything, grafted tangentially onto each other. However, with Yindi also taking an interest in Drexler’s misdeeds, that does appear set to change.

To look at the art style – put it politely, you can tell it’s an independent production. (Though I do the mainstream comics industry a disservice, as it would take a truly gifted amateur to rival the depths Rob Liefeld used to plumb.) But it does the job well enough, and has some real flair on wider, more scenic panels. Sad to say, it falls down a bit on its character models, which are stiff at the best of times. Its fight scenes are ok, but one panel, where from context, Cain has jerked awake from a troubled sleep, seems almost totally motionless.

The Resurrected has all the signs of shaping up into something interesting – most of my criticisms, after all, have been that it hasn’t explored plot points as thoroughly as I’d have liked. And a bait-and-switch where a plot about cyberpunk not-zombies quickly gives way to a meditation on personal identity in the wake of colonialism seems like the kind of shake-up the medium needs.

Most promisingly of all, even though Mr. Calypse is clearly a bad egg, the series tends to reject any crude division of people into good and evil. Yindi’s rejection of both Cain’s offer to come back into the fold of the dirty business we call society, but also of Pem’s militancy, would seem to indicate that the series isn’t going to fall into a simplistic, literally black-and-white narrative, where the marginalised sort out their oppressors and then everything’s idyllic forever. You could ask the cast of Orwell’s Animal Farm about that – or alternatively Robert Mugabe, though I suggest you stay out of arm’s reach.

Find out more about The Resurrected (and read a sample) here

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.