Before WarioWare came along, Wario had struggled to emerge from Mario’s shadow. He was cruder and chunkier, but still, most of his game outings were pretty much the same as Mario’s: platforming, collecting coins, etcetera. There wasn’t much practical difference between Mario Land and Wario Land, and usually he’d just be another face in the roster of Mario Tennis or some such.

More saliently, Wario may have been one of the first examples of the lazy evil-mode reskin (a type which reached its nadir with Sonic The Hedgehog’s Shadow, simply Sonic painted black). Wario at least looked slightly different, with a jagged moustache and a seasoned alcoholic’s purple nose, but at the end of the day was still basically Mario with the M upside down.

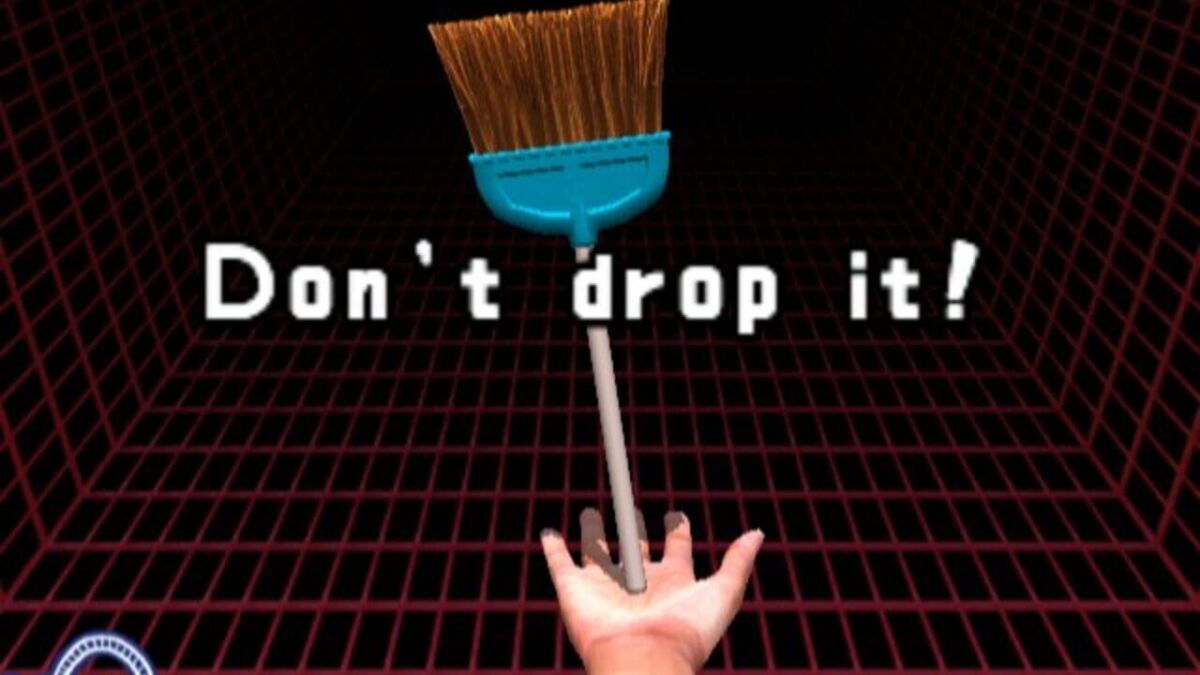

But WarioWare changed all that. Mario had his own minigame compilation, Mario Party, and even though it’s well over a dozen instalments in, it was never a brilliant game, hobbled by its clunky board game mechanics (for our younger readers, board games are what we invented video games to get away from). Where Mario Party was plodding and pedestrian, WarioWare was rapid-fire and gleefully random. It threw the player headfirst into a microgame and left them to puzzle out the controls within a five-second time limit. You might get frustrated, especially as it sped up to frantic speeds, but you simply wouldn’t have time to get bored.

Here’s the history of the WarioWare games over the years.

In The Beginning (WarioWare, Inc.: Mega Microgame$!, WarioWare, Inc.: Mega Party Game$!)

The original WarioWare, Inc.: Mega Microgame$! on the Game Boy Advance came with its rapid-fire core fully formed. In Japan, it bore the slogan “More! Shorter! Faster!” (originally “Saita! Saitan! Saisoku!”), which should tell you something. In both its ethos and style of humour it resembled mid-nineties British sketch outfit The Fast Show, whose mission statement was “character comes on, someone shouts ‘ARSE!’, bang, next sketch”. WarioWare has always been slightly more PG than that, but doesn’t shy away from the scatological, with one particularly iconic microgame simply being getting the timing right to pick your nose.

(Though apparently the developers’ free-form approach to suggesting microgames did turn up a number of ideas that were too obscene for publication – as well as some that were simply too colloquially Japanese for global audiences.)

The plot seemed to be that Wario, alongside a gang of wacky characters (a dog and cat duo who drive a taxi, etc.) had somehow managed to monetise these microgames, or something – it didn’t matter. It wasn’t important. The fun of it was in the rapid-fire approach, where you might end up doing anything from volleyball to shooting down nuclear missiles.

Mega Microgame$ drew rave reviews across the board. Edge called it one of the best games of its era, describing it as “a masterclass in how to captivate”. Even those who slated it as a fairly shallow experience – which, to be fair, it is, it’s not a JRPG – had to admit how much fun it was.

The follow-up, WarioWare, Inc.: Mega Party Game$! was essentially a remake of Mega Microgame$ for the GameCube, and its critical reception suffered slightly for that reason. However, the critic tends not to be playing from the comfort of a couch alongside three friends. The handheld-based Mega Microgame$ did have a multiplayer function, but that necessitated fumbling about with link cables. Mega Party Game$ was fundamentally more suited to it, with ‘Party’ right there in the title.

Most of the microgames can be enjoyed alone, but some only really worked with a competitive element – like racing paper planes, or crawling to the middle of a yoga mat. These could get enjoyably frantic with just two people, and with four it became outright mayhem.

Despite being a remake for the home console market, Mega Party Game$ drew in respectable reviews across the board. The only real complaints were that it was too like Mega Microgame$, both in terms of the recycled material and the graphics being fairly simplistic, especially for a home console. Both these points are true, but the fact is, it didn’t need photo-realistic graphics. Especially not when, as many of the microgames do, it was recreating 8-bit games of Nintendo’s past – and even those that weren’t tended towards the cartoony.

At The Periphery (WarioWare: Twisted!, WarioWare: Touched!, WarioWare: Smooth Moves, WarioWare: Snapped!)

Nintendo has been well-known for its dabbling in weird peripheral gadgets ever since the days of the NES and the Light Gun. WarioWare: Twisted! on the GBA limited this to the game cartridge itself, which had an in-built motion-sensitive gyroscope. Inevitably, this saw a lot of the games leaning in the direction of spinning things round. Nothing overly complex – the originals had, after all, only used the directional controls and the A button, and this system was equally intuitive.

It’s perhaps no coincidence that Nintendo would revisit exactly this element of motion sensitivity with their later consoles, the Wii and the Switch, given that IGN hailed Twisted as the best Game Boy Advance title there ever was – and that was up against some stiff competition, including many perennial favourites like the third generation of the mighty Pokémon games.

After the Game Boy Advance came the Nintendo DS, whose big new feature was a touch-sensitive screen. Sure enough, one of its launch titles and proving grounds was WarioWare: Touched!. Introducing hands-on interaction, and, to a lesser extent, microphone controls, gelled perfectly with WarioWare’s straightforward gameplay: for instance, there was already a microgame where you drew a line with a crayon. As with Twisted, even a newcomer could get the hang of these new controls almost immediately.

Touched also had a range of unlockable toys you could poke at with the stylus. From playing a miniature piano to just jiggling a pudding about, even if they wouldn’t hold your attention for very long they were all pleasingly silly. In a lot of ways these were like those silly apps from the early days of smartphones (drink the beer, light the lighter, etc.) before their time.

The touchscreen controls may have polarised the critics, but not to the point that any of them gave it what you could call a bad rating. Review aggregator Metacritic puts it on a healthy 8.1 out of 10 and most of the negative points are familiar ones: shallow, gimmicky, or, by now, that the core concept simply isn’t as fresh as it once was.

WarioWare: Smooth Moves returned to using motion-sensitivity, but this was with the Wii, a home console, which again opened the door to couch-based multiplayer. While it was slightly more fiddly to use the peripheral in Smooth Moves, having to hold the Wiimote in one of nineteen different positions depending on the game, it still attracted rave reviews – the Official Nintendo Magazine reckoned that Smooth Moves had placed Wario “alongside Mario and Link as a true Nintendo great“.

Yet curiously, the next game in the franchise, WarioWare: Snapped!, was a bit of a misstep. Admittedly Nintendo’s fanciful gimmicks producing three successes in a row was more than anyone could have hoped for, but here the gimmick wasn’t a new one. Using the DSi’s camera to pick up the player’s head and hands, it was essentially the same medium as Sony’s EyeToy: a peripheral device that had debuted five years beforehand.

It didn’t take players long to figure out you could game the EyeToy by holding your hand right up to the lens. Snapped didn’t quite go that far, since it was usually an uphill battle to even get the camera to register your presence – and when it did, it would represent you as an eerie silhouette. Most critics rated it a tepid four or five out of ten, and even IGN’s incongruous 7.8 out of 10 review was given with the caveat ‘when it works’.

Wario Land Infinite (WarioWare D.I.Y., Game & Wario, WarioWare Gold)

WarioWare D.I.Y., the last of the WarioWare games to grace the DS, was pretty much what it said on the tin. Now players could design their own microgames, prefacing the very successful Super Mario Maker. This may have been the perfect choice for this stage of the franchise, since if there’s one way the games could get old, it’s seeing the same microgames over and over.

The sheer range of games, and of their visual styles, had always been a part of WarioWare that attracted particular praise. Now this was opened up to the public, and wasn’t just a matter of stitching together a few pre-made assets. It was a surprisingly robust tool, allowing for all sorts of nonsense, coding as accessible as it could ever be, and even a crude-but-functional music studio.

After the disappointment of Snapped, D.I.Y. returned to the usual incredibly good ratings, averaging between 8 and 9 out of 10. Even Eurogamer’s relatively low-scoring review called it an ‘effortless piece of cleverness’. Sadly, sending and receiving home-made games was discontinued in 2014, but by then D.I.Y. had been out for almost five years – well over a video game’s average lifespan.

Game & Wario, from its title on down, was harking back to Nintendo’s ancient Game & Watch systems – and this wasn’t a good thing. Despite the franchise’s well-stocked back catalogue, Game & Wario offered a mere sixteen minigames. That’s right, not even microgames, not the ultra-brief experiences the franchise was known for, but the kind of things you’d expect as side content to a larger game.

The reception wasn’t as bad as Snapped, but not much better either. There were a couple positive reviews, although even these had to admit its range of game options was fairly sparse. GameInformer focused more on it being a showcase of what the Wii U could do. Eurogamer were particularly scathing, saying “If you expected breezy old Wario to make sense of the Wii U in some fundamental manner, you’re going to be disappointed…in Game & Wario’s least inspired moments, what you’ll get can feel uncomfortably close to an inquest.”

But if Game & Wario sounds like an oddity within the WarioWare franchise, that’s because it is. Originally, it had been a tech demo intended to come pre-installed on the Wii U, only to become slightly too big and complex. So it was hastily rejigged into a separate title, and, here’s the key, only then was turned into a Wario game. Here, again, we have Wario distinguishing his own identity as a Nintendo A-lister. Mario’s the platformer guy, Link’s the action-adventure guy, and Wario? Wario’s the go-to minigames guy.

WarioWare Gold couldn’t help but be a return to form after the disappointment of Game & Wario. As the title suggests, it collected some of the best-loved microgames of the franchise, but added some new ones as well — they weren’t just resting on their laurels. Even so, the classic material had all been overhauled to the point that some reviews couldn’t even tell they were revisiting the old stuff.

The Future (WarioWare: Get It Together!)

September this year will see the release of WarioWare: Get It Together! – and this is for the Switch, the physical manifestation of Nintendo throwing up their hands and making a console that’s both home-based and handheld. To put it another way, it’s a long-awaited return to couch-based multiplayer, which has traditionally been WarioWare’s most fertile territory.

Although only one preliminary trailer has been released, Get It Together is, again, tinkering with the WarioWare format. It’s set to introduce a co-op mode, and making the cast of characters something more than merely cosmetic backstory, including them as avatars and giving each of them a slightly different method of interacting with the microgames. It’s not a massive change, but as we’ve seen, these little experiments have tended to yield great results.

READ MORE: The History Of Far Cry

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.