When navigating confusing social dynamics and a period where awkwardness permeates the fabric of growth, adolescents often wish for an escape. Self-acceptance can feel unattainable. How can a person focus on their individualism when seeking validation from others? The high school years prove particularly strenuous on self-esteem when surrounded by peers who fuel an individual’s own internalised inadequacy. When other people fail us – including ourselves – we turn to other sources for comfort. Sometimes, animals bring out the best personality traits we fail to recognise in ourselves.

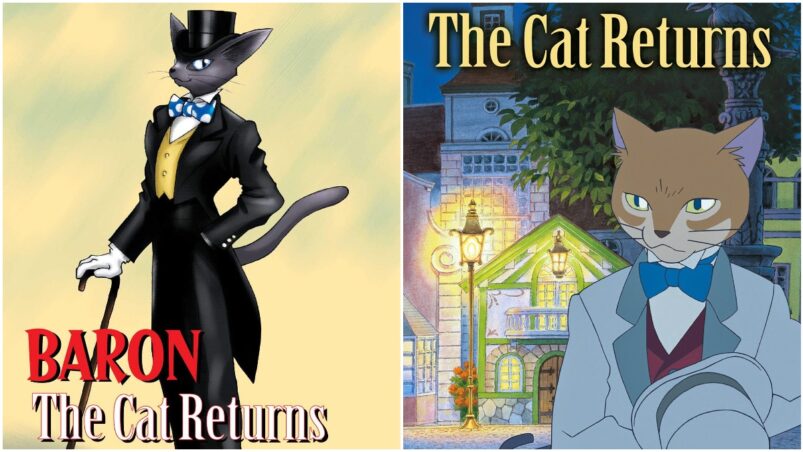

Acclaimed Japanese animation studio Studio Ghibli adapted author Aoi Hiiragi’s manga, Baron: The Cat Returns into a film in 2002. The Cat Returns, or Neko no Ongaeshi, is the first and only theatrically released spin-off film from Studio Ghibli. The starring cat statue from Ghibli’s Whisper of the Heart returns as one of the main The Cat Returns protagonists. Again, the studio adapted Whisper of the Heart from Hiiragi’s original manga series. The fantasy film adaptation directed by Hiroyuki Morita largely retains the manga’s character designs, pacing, and plot. However, a few changes divide the tones of these charming tales.

In both the manga and the film, the plot is straightforward. Awkward teenage girl Haru forcefully enters a world inhabited by anthropomorphic cats after she saves the Cat Kingdom’s prince from being hit by a bus on her way home from school. As a result, Haru begins transforming into a cat. Piling onto her feline predicament, the eccentric Cat King wants to make Haru marry his son, Prince Lune: the cat she rescued from death. Through the help of the transforming cat Baron and his fluffy sidekick Muta, Haru tries to escape the bizarre cat universe.

Baron: The Cat Returns acts as a self-contained story. Divided into three chapters, “The Cat Returns,” “The Cat Office,” and “The Kingdom of Cats,” one can read the manga in one short sitting. The same can be said for the film. Clocking in at only 75 minutes, The Cat Returns moves quickly. Each manga chapter essentially represents the film adaptations’ three acts. However, Ghibli’s The Cat Returns adds fundamental expansion to a few underdeveloped scenes from the manga.

Firstly, the film and the manga offer different interpretations of its protagonist, Haru. Hiiragi’s Haru adopts more manga or anime-typical characteristics. Here, Haru is pretty boy-crazy, obsessing over her pretty boy classmate Machida quite frequently. Lines protruding outward, encircling Haru in the panels, or exaggerated eye shapes indicate her sensory disruption whenever Machida influences her emotions. Contrastingly, the film assigns Haru’s friend Hiromi (played by Kirsten Bell in the English dub) this romantic infatuation. But Haru’s swooning over a boy in Baron: The Cat Returns explicitly affects her attitude toward life. Awkwardness resonates strongly in the manga, as opposed to the generally recognisable teenage awkwardness Haru demonstrates onscreen.

The manga does spend more time developing Haru’s relationship with her best friend Hiromi. When Haru saves Prince Lune, she uses Hiromi’s lacrosse stick to scoop him out of danger, subsequently snapping the stick in half. Later, Hiromi accuses Haru of breaking all her lacrosse sticks when the Cat Kingdom cats begin infiltrating Haru’s life. The incident places a strain on the girls’ relationships. Their fracturing friendship casts an emotional weight on Haru since she has only one friend and already struggles with morale. Hiromi’s significance in Haru’s character development throughout the manga feels vital. In the film, Haru acts more reserved. She feels affection for Hiromi, but their connection doesn’t seem pivotal to advancing the narrative.

Additionally, Haru and her mother’s interactions carry differing importance when comparing the text to the screen interpretations. In probably the most poignant scene in the film, Haru’s mother lovingly reminisces on a time when she found Haru as a child feeding a bedraggled white kitten. Voice humming with warmth for her daughter, her mom remembers how Haru told her mother she could talk to the stray cat. Soft piano music accompanies the heartwarming scene drenched in fuzzy sepia tones. Shocked, Haru realises that her verbal conversation with Prince Lune after her successful rescue holds true. Haru’s acts of kindness foreshadow her future in the narrative. Self-revelation takes place when she understands how she had been sabotaging herself with thoughts of self-doubt and inadequacy.

Despite her mother’s prominent presence in the manga, the relationship between mother and daughter lacks the emotional depth The Cat Returns adaptation supplies. The primary film scene involving Haru and her mother prepares the path for her character development (and also involves a major plot point reveal later). However, the numerous scenes the manga includes with the two characters point to silly attributes Haru lacks in the film version. When the Cat Kingdom begins sending gifts to Haru as a reward for acting as their Prince’s saviour, Haru’s mother intercepts one gift: boxes of canned mice. The two share a moment of bewilderment on the page, diffusing the strangeness through shared awe. Hiiragi’s depiction of Haru as exhibiting fluctuating emotions yet still relying on her mother’s visual reactions changes Haru into a more co-dependent character.

Art evokes emotional responses from audiences. Both manga and film draw their characters nearly identically. The mediums utilise simplistic facial features on human characters to highlight the detailed diversity of their cat portrayals. The Cat Returns film has been criticised for not living up to the Studio Ghibli animation standards the company is known for upholding. Viewers specifically condemned the lacklustre detail and whimsicality in flying scenes. In contrast, Hiiragi’s manga fleshes out two-page spreads with God’s eye viewpoints and intricate linework. She composes a gorgeous scene where readers might feel vertigo looking down at the landscape below. Upside-down waterfalls stream from the sky in the Cat Kingdom. Hiiragi reveals an eye for architecture and interior design as Haru gapes at the splendour of the Cat King’s palace.

While the artistic judgments of the films’ dimmer colour scheme and rudimentary art choices are valid, one must also acknowledge how it pays wonderful attention to the cat character designs. The adaptation draws inspiration from the manga’s illustrations. Yet, the animation offers slightly cuter cat representations. Instead of pointed ears, the ears of Natoru the cat are altered to resemble the folded over ears Scottish Fold cats possess. The cats’ snouts protrude in the manga, and their eyes take a realistic almond shape like real cat eyes. All cats in The Cat Returns film bear smaller snouts and circular eyes instead. Where Hiiragi’s tuxedo bodyguard cats sport black-mask-like fur markings on their faces, the Ghibli cat design removes the mask to further contrast their white heads and black-furred bodies emulating the look of a human tuxedo. The changes are slight but noticeable.

Overall, the biggest disparities between mediums involve altering what the Cat Kingdom represents, and the relation of a specific cat to Haru. These details will spoil both the manga and the film, but they do markedly change the tones. In some ways, a grim revelation gives the Baron: The Cat Returns manga a more unsettling vibe. On the other hand, Haru’s unhinged expressions and behaviour in the book specifically mirror trademark manga humour readers enjoy. The manga also dials down the fat-phobic jokes about Muta that sour the film somewhat.

Somehow, The Cat Returns exists in the Studio Ghibli animation universe, and cat-lovers everywhere should be grateful. Both film and manga decided to tell a slightly creepy story where an angry cat overlord wants a human girl to marry his cat son. Ultimately, The Cat Returns is worth watching and reading. The relatable teenage protagonist learns valuable lessons about self-love, self-worth, and self-acceptance – through the aid of some extremely cute cats.

READ NEXT: How Does When Marnie Was There Compare To Its Studio Ghibli Movie?

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.