The final installment in the ‘Project Itoh trilogy’ marks Shūkō Murase’s return to form and his first solo foray into feature animation, following his contribution to Dante’s Inferno: An Animated Epic. Released after a two-year delay (caused by the Manglobe studio bankruptcy), Genocidal Organ (originally, Gyakusatsu Kikan) is another fine tribute to Satoshi Itoh (1974-2009) whose highly acclaimed debut novel (published in 2007) it adapts for the big screen.

Superficially, the film appears as a spy thriller with the elements of war drama and science fiction, but once you scratch the surface, you are faced with an array of questions regarding plenty of burning issues: terrorism, American involvement in foreign conflicts, the gap between developed and struggling countries, heightened security measures and its (negative) effects on one’s privacy, to name a few.

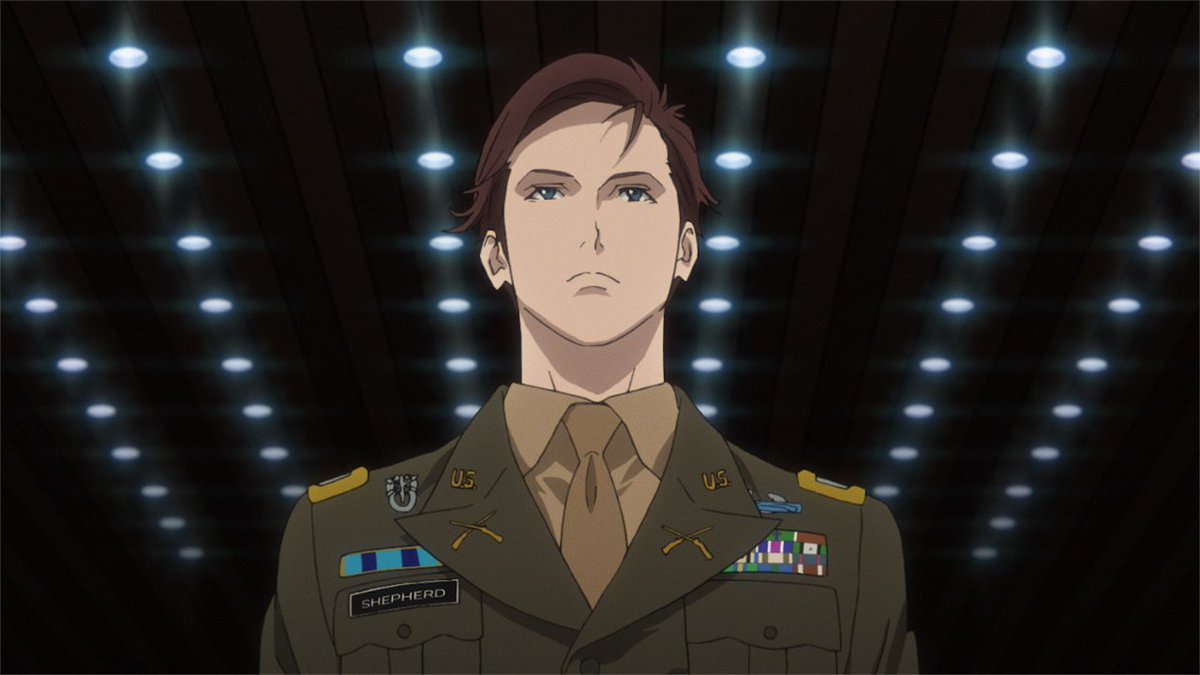

Brutal, engaging and unrelentingly bleak, it is set in the near future that eerily parallels our present reality screwed up by the proliferating social illnesses, from political disagreements to religious fanaticism, and constantly on the verge of widespread chaos. Told from the viewpoint of a US special forces captain, Clavis Shepherd, it brings the story of a world ruled by apathy and carnage from two different sides of the wall that separates capitalist empires and the transitional periphery, so to speak. Built after a nuclear attack that leveled Sarajevo to the ground, this ‘wall’ is maintained by an enigmatic figure named John Paul who seems to have developed an ability to ignite murderous rage in people of various nations, causing civil wars.

And that is where the intriguing concept of the titular ‘genocidal organ’ or rather, ‘innate grammar of genocide’ comes into play, accompanied by the meditation on freedom, psychology, (distorted) ethics and the manipulative power of language, inter alia. Murase is no stranger to philosophical discourse, considering his work on Ergo Proxy series, so the viewers unfamiliar with his approach might find the screenplay too talky for its own good. On the other hand, he manages the action with brutal intensity, not shying away from graphic depictions of violence, so just when you’re lulled into a state we could dub as ‘intellectual stupor’, he packs a hefty, blood-soaked punch.

What makes his latest offering stand apart not only from other anime, but also from plenty of live-action movies of our time is his insistence on blurring the boundaries between a hero and an anti-hero. Clavis is, essentially, a desensitized drone who operates on a potent mixture of PTSD blockers and takes the killing as ‘a normal job’, whether his victims are rogue generals or brainwashed children. To paraphrase one of the side characters, ‘he is built to see only what he wants to see’, unfazed by the bloodbath he and his ‘colleagues’ cause. Not unlike him is John Paul whose agenda is tightly connected to the ‘genocidal linguistics’ and is focused on protecting the status quo of selfish indifference toward the suffering of others. It is a dire situation they both create, with not a single trace of hope or optimism to be found.

Genocidal Organ keeps its serious tone primarily by virtue of the semi-realistic artwork supported by superb voice-acting and Yoshihiro Ike’s evocative, yet unobtrusive score. Naoyuki Onda-esque character design is perfectly fitted with the painterly backgrounds varying from Prague exteriors to comfy apartments in which the protagonists enjoy their bottle of Budweiser, home-delivered pizza and the American football match. Truth be told, the production hell has left noticeable scars in the animation quality, but fortunately they are not a major distraction, especially not in the light of the film’s disturbing insightfulness.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.