Let’s play pretend for a moment. Let’s say you’re white, rich, your dad has plenty of connections and you wind up studying English Literature at the University of Cambridge. If you do, you’ll probably wind up doing a lot of Practical Criticism.

Developed by I.A. Richards in the 1920s, it’s the act of looking at a given piece of literature -a bit of prose, some poetry, or a few scraps of a script- without any sort of context. When you do Practical Criticism, all you get is the text. You don’t know about the author, you don’t know the date, the country of origin, the exact genre, sometimes you don’t even know the title. Richard’s idea stood that a critic should engage with ‘the words on the page’ and literally nothing else. It’s an attempt to escape preconceived notions about any given text. Richard wanted his students to like Shakespeare not because Shakespeare is Shakespeare, but because Shakespeare is good.

Obviously, I don’t go to the university of Cambridge. Of course I don’t. If I did, I wouldn’t be writing for Cultured Vultures, I’d be taking a bath in all my lovely, lovely money. But I got to do some of my own practical criticism when I went to see Brigsby Bear at the Odeon Screen Unseen event a few months ago. I’d never heard of the film before, so, sitting down to watch it, I had no idea what to expect. And halfway through, I realised that not knowing what to expect was kind of weird for a film in 2017. If you have the internet, and of course you have the internet, you’re reading this, it’s hard -really hard- to walk into a piece of media without any idea what you’re in for. Coverage of film, of fiction, has existed for as long as either have existed, sure, but it’s never been quite so prolific and terrifyingly omnipresent as now, when all the information you might ever want about a given film exists in your pocket; a few taps of a smartphone’s touchscreen away.

Today’s media landscape is obsessed with extended universes and cameos, references, in-jokes, fan-service and sequels. It’s built off the back of fan theories and fan-wikis, YouTube commentators, bloggers and wanky think-pieces like this. It’s always been true that fiction is bigger than fiction, but it’s truer now more than ever. Modern media doesn’t just demand a deeper level of investment than ever, it forces you to invest, with trailers and analyses of the trailers and leaks and coverage and reviews and previews and think pieces and videos and apps that extend the canon. It’s amazing, it’s a marvel of modern technolog; it’s all your connoisseur Christmases come at once and I wouldn’t have it any other way. Whatever you love and however you love it, there exists a community of people out there who love it just as much. It’s a part of what it means to consume media in 2017 (shame Net Neutrality’s going to ruin it, though, right?).

But, sometimes, that omnipresence denies fiction a sense of mystery. It’s hard to wade through all that content without soaking some of it up, without developing opinions through osmosis, without having at least heard and in having heard, formed an opinion on- pretty much everything that’s out there. Surprising stuff exists, but manufacturing and experiencing that surprise; in earnest, rather than vicariously, is getting more and more difficult.

So, yeah, it occurred to me, halfway through Brigbsy Bear, that my experience with it was kind of beautiful. That it was unique and rare and weird. That I’d never really had the chance, not since I was a kid buying bargain bin PS22 games, to sit and let a piece of media have its way with me. I loved it.

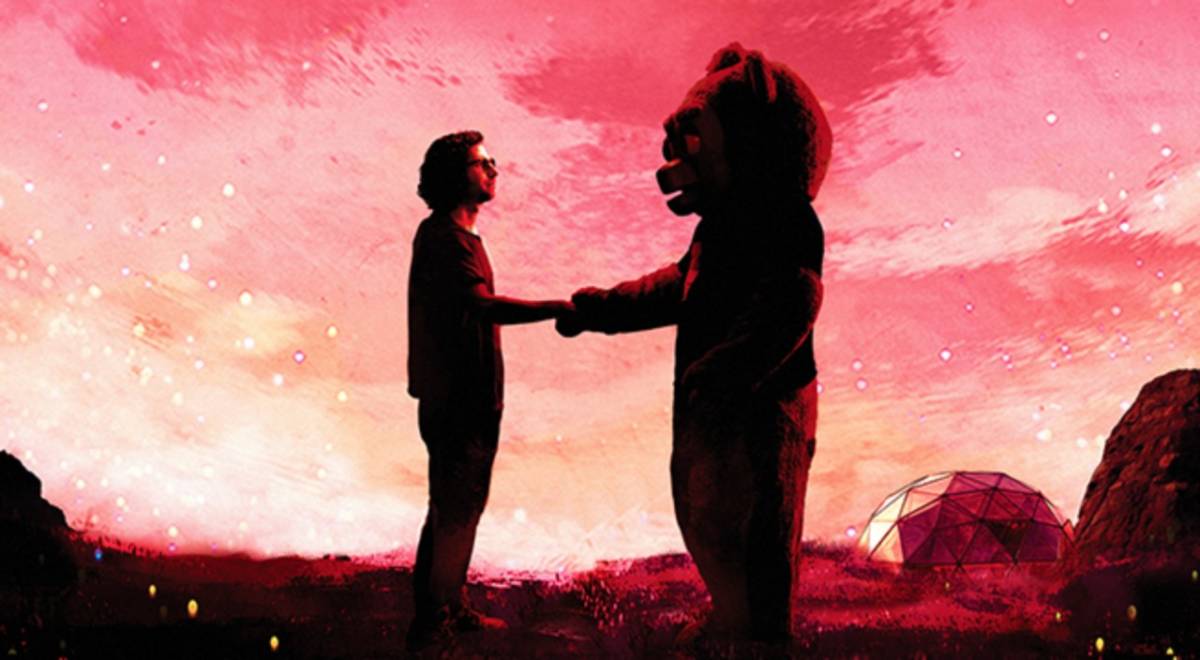

Watching Brigsby Bear without any idea as to what it might be, allows it to wrongfoot you. To shift and change and become something you don’t expect. It’s about a boy -James, played by Kyle Mooney- who’s kidnapped and taken away from his parents at birth. His kidnappers become surrogate parents. Creepy surrogate parents, who lock him away in an underground home and tell him everything else, the rest of the world, is a nightmare wasteland. His only connection to the outside world is a children’s educational TV programme, Brigsby Bear, made in secret by his ‘father’ (brilliantly, creepily played by Mark Hamill). When the FBI find out where James is and take him back to the real world, he’s a fish out of water, with no understanding of, or interest in, how the real-world works. All he can think of is Brigsby, and the eventual creation of a film, long denied him, becomes the only possible form of therapy. It becomes the sole lens through which he finds meaning. It’s big and life-affirming and funny and strange. Even if I’ve just spoiled it for you (and don’t say it wasn’t your fault), you should go watch it.

Of course, watching it the way I did makes it all the better. If you don’t know what to expect, James’ isolation becomes the audience’s. The film’s opening scenes, dominated by the cluttered claustrophobia of James’ underground home, by gas masks and alarms, air-filters and curfews, seems every bit as post-apocalyptic to us as it does to James. The animatronic animals outside the house, placed there by James’ father as a source of entertainment seem strange, but we connect them to a wider narrative. We let our imagination fill in the gaps, to concoct a world in which it all makes sense. We accept the anomalies just like James does. So, when the FBI appears on the horizon, lights ablaze, it seems just as weird, just as frightening to us as it does to him. The film’s inciting action comes loaded not just with the promise of conflict, not just with the promise of the film’s wider mysteries, but with the promise of a new, external force, one just as mysterious to us as the protagonist.

When they arrive, the nature of the film seems to change. Or at least we think it does. We see it shift from a story about post-apocalyptic society to a similarly nightmarish story about an oppressive government. Then, when the weird nightmare fascist police force is revealed to be, you know, the normal police. The narrative changes again. This time, you think, it seems to be about social isolation; a traumatic drama with a weird, surrealist edge. When the film finally turns around and becomes the inspiring little project it is, though, it’s all the sweeter. Your surprise is everyone else’s. You’ve been wrongfooted, toyed with, held in bitter suspense for almost two thirds of the film. You’ve walked into this film thinking it’s going to be nightmarish and grim and cynical. When the final project, the final narrative, is life-affirming, however -a heart-warming little story about taking what’s bad and making it good- the release is all the sweeter.

I know this isn’t particularly profound. You don’t need to be doing English at Cambridge to understand that it’s good to let stories surprise you. And I know, too, that in writing about Brigsby Bear I’ve sort of stopped you from having the same experience as me. But I wanted to commemorate what I thought was a pretty special, pretty rare experience with fiction. To celebrate it. So thanks, Brigsby, thanks for making my world -and James’ world- a little bit less shit.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.