It’s a little strange just how intuitive we find the idea of each decade having its own distinct culture. As a great philosopher once told us, time keeps on slipping into the future – by which I mean, when the year 2019 rolls around in a few months, it’ll look a lot more like 2020 than it does 2010. But nonetheless, these randomly-determined sets of ten-year time periods carry with them clear and consistent images. If you hear of the 1960s you think of swarms of young hippies wandering Woodstock field, and when I say the 1980s, you imagine high-powdered businessmen in flash cars with wide, wide lapels.

Granted, these are stereotypes, and pretty broad-brushed stereotypes at that, but stereotypes exist for a reason. It never does to pre-judge anybody, but if you meet someone who came of age in the ‘70s, it’s perfectly possible they’ll have fond memories of The Who. Decades are, more than anything else, defined by the cultural influences that were popular at those times – even the current events of the day, i.e. the things that actually happened, get consumed and writ larger in popular culture.

The ‘60s – Monty Python’s Flying Circus

Nowadays plenty of comedies will pull out a wild non-sequitur in place of actually writing a joke, hoping the sheer random factor will translate as silly rather than contrived. But when Monty Python was first launched upon an unsuspecting public, there had simply never been anything like it before.

The Pythons themselves were impeccably educated Oxbridge graduates, and it showed. The series was full of classical references, but chopped-up and played upon and gently mocked in an utterly surreal way. Want proof? Look no further than Terry Gilliam’s marvellous stop-motion opening credits – that jaunty theme music is Sousa’s ‘The Liberty Bell’, and the foot which crushes the titles belongs to Cupid, from Bronzino’s ‘Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time’.

If there is any comparison you could draw, it’s probably to Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’, itself a founding document of the hippy subculture (although it was written in the ‘50s) – a work which had a solid awareness of the Western canon from whence it came, but which simultaneously broke all the rules of that culture. One big example in both is the frank admission that homosexuality existed and wasn’t necessarily sent by Satan to cause flooding – something which Ginsberg and Python Graham Chapman both knew very well.

The Pythonesque style is probably best summarised by the now-infamous Dead Parrot sketch, so popular the Pythons themselves got sick of doing it. A relatively benign man-walks-into-shop setup quickly spirals off into an utterly absurd argument – and then, just as that threatens to begin flagging, the shop owner takes a wild left turn and launches into a musical number about how he’d always wanted to be lumberjack.

As a result of the Dead Parrot sketch, if a work of comedy refers to a parrot in any shape or form, there are incredibly good odds the parrot will be of the ‘Norwegian Blue’ breed. This is just one of a million ways the Pythons have influenced the wider culture – one particularly notable one being the art and animation styles of adult cartoon South Park, which was heavily influenced by Gilliam’s cut-out cartoons (as was the overall tone, particularly in its early days).

Although Flying Circus itself ran into the doldrums when John Cleese left, folding altogether not long afterwards, Cleese remained involved through the various film adaptations, all of which were as well-received as the TV series, if not more so. The last of these, The Meaning Of Life, was released in 1983, which gives you some idea of how robust a format it was, and although this marked the end of the Pythons’ prime era, to this day the surviving members still reunite for the occasional live show.

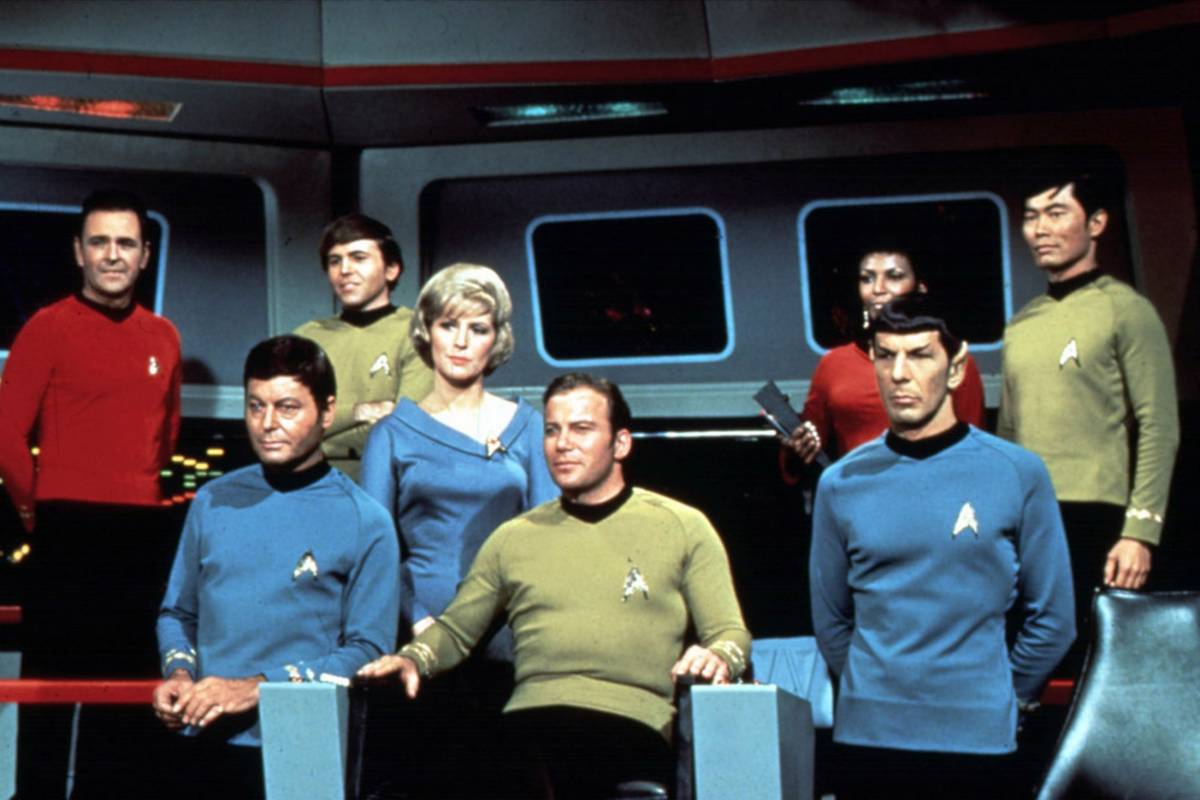

Honorable mention – Star Trek

epictimes.com

While of course most people in the ‘60s spent their days wearing bell-bottoms and dropping acid, man, the decade also saw fragile squishy humans slip the surly bonds of earth and literally walk on the moon. The space race breathed fresh life into the sci-fi genre, and although this era saw the likes of Philip K. Dick and Ursula LeGuin hitting their stride as authors, the most prominent new entry in the genre was, without a doubt, Star Trek. Tales of space travel and alien creatures were beamed directly into people’s homes in an age when most people remembered having to get about by horse – after that, no wonder a jaunt to the moon seemed doable.

Star Trek is a fairly sprawling franchise, but even now the original series holds up reasonably well. Sure, it can’t quite shake off the era it came from – few real female astronauts ever wore miniskirts on duty, and the special effects can’t help but seem primitive, but at the same time this helps to contextualise it as coming from a time when this was the absolute cutting edge.

The ‘70s – M*A*S*H

Even though North Korea’s wacky antics can still grab the headlines, the war that split the Korean peninsula in the first place finds itself halfway-forgotten by history. In its way, this is to be expected – it’s overshadowed on both sides by its more telegenic brothers, World War II and the Vietnam War, both of which also had the advantage of ending with one side the clear victor, rather than in a why-bother stalemate.

M*A*S*H is a rare exception to the Korean war’s yawning absence from popular culture – although despite that setting it should be said, between the helicopters in the opening credits, the focus on war being hell, and the wider ruminations on America’s place as a military empire, it was a show for the Vietnam era through and through.

Although M*A*S*H began as a largely straight comedy – an unconventional but effective choice for a show set largely in field operating theatres – there was a distinct sea change after the third season finale. After an episode of the usual Korean-war chuckles, focused on the lighter note that Henry Blake (McLean Stevenson) was being rotated home, the ending hit us all with the shock revelation that Blake’s plane had been shot down with no survivors.

After this sobering climax, the show began to leaven the comedy with outright dramatic storylines. It’s been argued that this was key to the show’s longevity (seven years longer than the Korean War itself), with the shift in tone allowing previously flat characters to acquire a bit of depth. This didn’t come out of nowhere, either – since the beginning the creators had been pushing back against the conventions of the sitcom format, in particular the much-hated laugh track. By their insistence, the laugh track was strictly kept away from scenes in the operating room (for obvious reasons) before ultimately being dropped altogether.

There was also the fact that before this, few shows had the guts to kill off significant characters and have them stay dead, which would have made it terribly difficult to convey the actual gravity of war. And while M*A*S*H did bring in new faces to fill the combat boots of those who had left, these additions were welcomed by the fanbase – again, I point to the show’s longevity.

While the ‘60s may have been over, the show wasn’t afraid to take experimental approaches to its artistic direction. The episode ‘Point of View’ was, appropriately enough, seen entirely through the eyes of a wounded soldier. ‘Hawkeye’, meanwhile, consisted of a single extended monologue from the main character. And – adding fuel to the fire of the show having a lot more to do with Vietnam than it did with Korea – ‘The Interview’ was a mock-documentary made up of largely improvised interviews with the characters.

Although ‘The Interview’ is often cited as the show’s best episode, the finale, ‘Goodbye, Farewell, and Amen’ deserves some credit for its sheer reach. Fully 77 percent of the US television audience of February 28, 1983 were watching M*A*S*H, a total of over 125 million viewers – a record that stood for 25 years, and has only been surpassed by the Superbowl itself.

The ‘80s – Dallas

This runs right into what I said in the intro about decades bleeding into the ones on either side. Yes, technically Dallas began in ‘78, but it ran right through the ‘80s, and more to the point, it was far more in tune with the ideas and aesthetics of that decade than any other. With free market ideology dominating the West and with the economy booming, there couldn’t have been a better time for a show about the everyday problems of incredibly rich people.

Initially, Dallas was a kind of latter-day Romeo and Juliet story, focusing on Pamela Barnes trying to fit into the oil-baron Ewing family – the Barneses themselves being the Ewings’ long-time oil industry rivals, with the feud stemming from a bitter falling-out between their respective patriarchs. But this quickly gave way to a focus on the eldest Ewing son, the caddish J.R., who was too fond of Stetsons to strictly be in the mould of Gordon Gekko, but nonetheless firmly believed that greed was good – the perfect counterbalance to Pamela’s nebbishly good-natured husband Bobby.

The excess that seemed to suffuse every minute of the ‘80s wasn’t just limited to the characters’ lifestyles, it crept into the plotlines as well. Dallas was notorious for ending each season on a whopper of a cliffhanger to drum up excitement and anticipation for their return – most famous of all was the ‘who shot J.R.?’ mystery. Tops bearing the legends ‘who shot J.R.?’ and ‘I shot J.R.’ became incredibly hot sellers, threatening to beat out even pastel shirts. Nor was the hype limited to America – the UK’s Queen Mother was an avid fan, and a session of the Turkish parliament was suspended to allow its members to view the conclusion.

Another example of this came when, in an act of retroactive continuity that’s astounding even for a soap opera, the entirety of the ninth season – in particular, Bobby’s death – was revealed to have literally been all a dream. (A development which played merry hell with Dallas spin-off Knots Landing, which had repeatedly made reference to Bobby being dead – forcing Knots Landing to branch off into a completely separate reality.) This was the show’s way of dealing with the departure and subsequent return of Patrick Duffy (who played Bobby) and producer Leonard Katzman, both of whom were hastily roped back in by the production company when ratings began to wobble.

Although J.R.’s shooting was the high-water mark for the show in terms of viewing figures and cultural impact, it enjoyed high ratings and continued popularity for the eleven-year remainder of its run. In a wider sense, its sort of aspirational drama has never gone out of fashion since, and as such it must bear some of the dubious honour of having inspired Keeping Up With The Kardashians. The then-communist Romanian government broadcast Dallas in an attempt to showcase American decadence, a decision which backfired tremendously as the little Romanians gazed in awe at the Ewings’ lifestyles – one can only imagine they’d have been more sceptical of Kim and Kourtney’s bickering.

The ‘90s – The Simpsons

Statistically, you already know this one – and even now it’s become part of the landscape, it looms large, but back then it was a titan. The Simpsons was an immediate smash hit, single-handedly turning cartoons into something that wasn’t just for kids, drawing disapproving grumbles from the Bush dynasty (to which they responded with such panache Barbara Bush apologised), and moving Pokémon-level amounts of assorted merchandise.

In large part, the show’s success came down to it being a revolution from the saccharine family sitcoms of the time, where father always knew best and we learned very important lessons at the end of an episode. In The Simpsons, meanwhile, every institution is flawed, from religion to the mass media, even – most importantly – the nuclear family. Far from a wholesome picket-fenced family unit, the Simpsons were prone to disagreements, bitter arguments, and genuine disconnects. Naturally the public identified far more with them than any of their prime-time rivals.

This was exemplified with Homer, the Simpson patriarch. A drinker and a gambler, Homer was an impressive collection of all of our lower impulses – at bottom, wanting nothing more than to watch TV with a nice beer. But it was his son, Bart – accurately self-ordained as ‘this century’s Dennis the Menace’ – who captured the popular imagination, at least at first.

The era of Bartmania was truly confirmed when schools started banning children from wearing the (omnipresent) Bart-emblazoned t-shirts, thereby cementing their status as the ultimate form of youthful rebellion. (Bootleg Bart t-shirts were and are a big feature of this – creator Matt Groening generally let ripoff merchandise slide, with the one notable exception being shirts depicting Bart as a neo-Nazi skinhead.) And of the questionable tie-in album The Simpsons Sing The Blues, it was ‘Do The Bartman’, featuring a height-of-his-powers Michael Jackson on backing vocals, that was the hit single, topping the charts in the UK and staying there for fully three weeks.

The Simpsons went hand in hand with the idea of the ‘90s as being the end of history. The Cold War was over (see: Rasputin The Friendly Russian, and the car Homer test-drives that comes from a country which no longer exists) and the West – or rather, consumer capitalism – had won. Everything was fine now. So why did it all feel so hollow?

The ‘00s – The Wire

Although the drug traffickers communicating by pager lent the first season a bit of a ‘70s stamp, that was for no less a reason than that it was drawing on real-life investigations from the ‘70s. The central dynamic of policemen vainly trying to stamp out people’s insatiable desire for opiates and the ensuing market for them was, and is, as relevant as ever. Ditto the degradation of the American city – if The Wire had a main character, it was Baltimore itself, though the same dynamics are in effect in pretty much any city of sufficient size.

The first season was straightforwardly a crime drama – albeit a very good one, with hints of the wider city politicking and power struggles that came further to the fore as the show went on. But while it was exactly that sort of crime drama – to wit, The Sopranos – that started HBO’s reign of hour-long TV drama in earnest, its merry cast of crims never came out with anything as poignant as ‘we used to make shit in this country, build shit – now we just stick our hand in the next guy’s pocket’, possibly because Tony Soprano couldn’t possibly have said anything of the sort without blushing.

It was The Wire’s second season, placing the dockworkers’ union front and centre, that confirmed it as the show of the post-industrial era. All of The Wire’s institutions are in decline, but it is the docks which seem to be in the final stages of decomposition before our eyes – this further collapse of Baltimore’s working class being yet another nail in the coffin of the American dream.

While it’s the 2010s which are known for being the age of fake news and incredibly shaky journalistic practices, that didn’t spring up out of nowhere. The fifth and final season threw us into the chaos of the Baltimore Sun-Times newsroom, which, like all The Wire’s institutions, is working for the benefit of some numbers on some spreadsheet rather than any living human person – but to many, this arc was seen as a misstep. As creator David Simon had been a reporter with the Sun-Times, it had the feel of a plodding, heavy-handed morality play, where an obviously bad egg fabricates stories and ultimately wins a Pulitzer for it, while his more upright colleagues are left to suffer.

The issue was that, as with jazz, you had to listen to the notes they weren’t publishing. The fifth season also had all the other plotlines coming to a head – but, when reigning drug lord Proposition Joe (the late, great Robert F. Chew) was bumped off in an outright coup, it barely merited a byline. The death of the legendary stick-up artist Omar Little, who the viewers knew and loved for five years, didn’t even make it into the paper. The rise and fall of new drug lord Marlo Stanfield, the plight of Baltimore’s school system, the union men who supped with the devil to try and save the docks – none of these made the printed page.

In this light, the story becomes about the news media’s utter disconnect from the people, and the places, it supposedly serves. This is a pattern we’ve seen evidence of time and time again ever since – for just one example, see the media’s utter frantic obsession with a certain American President, to the detriment of any serious analysis of the man’s actual positions or policies.

(These strongly-worded opinions are for entertainment purposes only. Please keep reading my article about classic television shows instead of any coverage of the ongoing war in Yemen.)

Honorable mention – Nathan Barley

This is a lesser-known entry in the well-respected canons of Charlie Brooker and Chris Morris, a niche, culty sort of thing – indeed, the critical verdict at the time was something similar, the consensus being that its focus on one particular substrata of the London media scene was simply too narrow a subject. And put like that, Nathan Barley does sound like it’s a bit of back-slapping self-worship from a pack of old chums firmly inside the ivory tower.

However, the titular Nathan Barley wasn’t just a standard Shoreditch twat, but a self-obsessed man-child who believed his worship of technology and new media placed him on the cutting edge of culture. That’s right, they predicted the modern hipster. It was niche at the time, but now everyone knows a Nathan Barley – and in another Cassandra-scale prophecy, one episode actually featured a magazine called VICE.

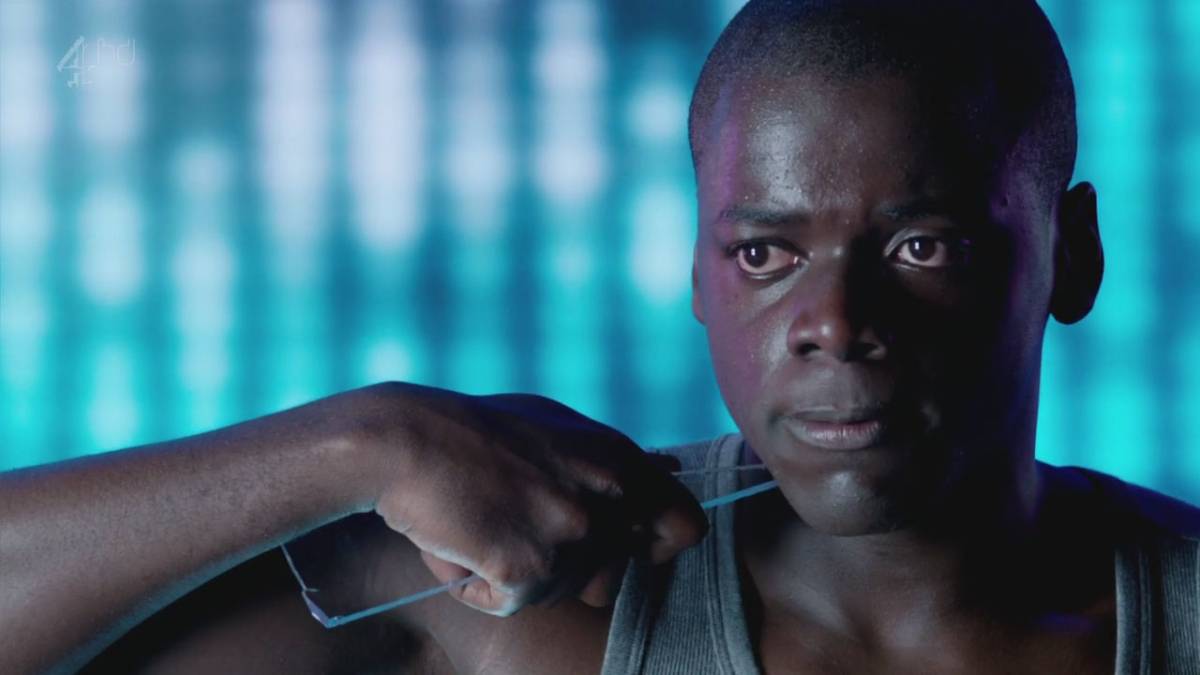

The ‘10s – Black Mirror

While there’s just over a year left for this decade to pull something else out of the bag, it’d have to be something pretty bloody special to topple Charlie Brooker’s more famous creation Black Mirror. An anthology show exploring any number of not-too-distant futures, Black Mirror is something of a cautionary tale for the information age, showing the potential horrifying consequences of our species’ love affair with technology.

While it’s created some marvellous speculative fiction, with the boxed-in dystopia of 15 Million Merits easily up there with 1984 and Brave New World, it’s possibly at its strongest with episodes like The National Anthem, which achieves the same kind of techno-fear using nothing more than the real-life technology we have at our disposal. You know, everyday, boring stuff, like the ability to broadcast video to anyone else on the planet using a single handheld device. (The title Black Mirror, of course, refers to those ubiquitous squares of metal and plastic, one of which you’re very likely reading these words on.)

In a 1953 essay, Isaac Asimov famously outlined three major subcategories of science fiction – gadget, which describes some new invention, adventure, where the new invention is used as a prop by the heroes, and social, which explores how the new invention impacts upon wider society. For Brooker, society’s love of screens has perhaps done a fair bit of the work already, but there’s no denying Black Mirror is social science fiction to the core. For instance, we have a little chip in our heads that gives us the power of perfect recall – and we use it to obsess over whether our wife is having an affair.

(For most of us, our own irrevocably flawed powers of recollection seem to be enough of a torment.)

Possibly one of the strongest concepts touched upon in Black Mirror, even if it was let down a little in the execution, was that of the online hate mob – which the episode ‘White Bear’ made flesh. Not for nothing is it said that the same crowd that cheers your coronation will cheer your execution just as vigorously. In White Bear, the mob’s victim du jour is a child murderer, but even with that unsavoury rap sheet you can’t help but feel that even she doesn’t deserve the Sisyphean treatment meted out to her – and lest we forget, social media has brought out the lynching rope for plenty of things which weren’t even crimes.

While the quality of the series dipped a bit when Netflix got their hands on it, they compensated for this with volume. These latter-day installments make a lot (too much, if truth be told) of use of the idea of people’s entire minds being copied and uploaded to the cloud, lending the mistreatment of what is ultimately software equivalent moral weight to the mistreatment of a human – a moral which will doubtless serve us well when artificial intelligence slouches out of Google to be born. However, it’s this device that gave us Black Mirror’s most uplifting moment to date – the ending of San Junipero, where an adorable lesbian couple ascend to immortality.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.