There’s a youthful energy imbued in every part of Videoverse. Its most obvious source is the youth of our teen protagonist, Emmett. Youth also emanates from the early internet age faithfully recreated in Kinmoku’s sophomore release. Back in 2003, the internet was in an awkward in-between stage – its own kind of adolescence. It was a wild-west really only properly inhabited by passionate communities of nerds and fanatics.

As these spaces matured and corporations became attuned to how they could be commodified, things changed. Videoverse presents an excellent portrait of people and relationships enduring this change. It’s profound. It’s heartfelt. It feels alive and organic. And as an added bonus, it’s actually also kind of hilarious.

As mentioned, Videoverse follows Emmett, a fifteen-year-old British immigrant living in Germany. He is a long-time user of the Kinmoku Shark, a fictional Nintendo DS-like game console with a webcam and an ethernet port. Between playing sessions of Feudal Fantasy, Emmett spends his time on the Shark contributing to forums and chatting to friends on the console’s social network, Videoverse.

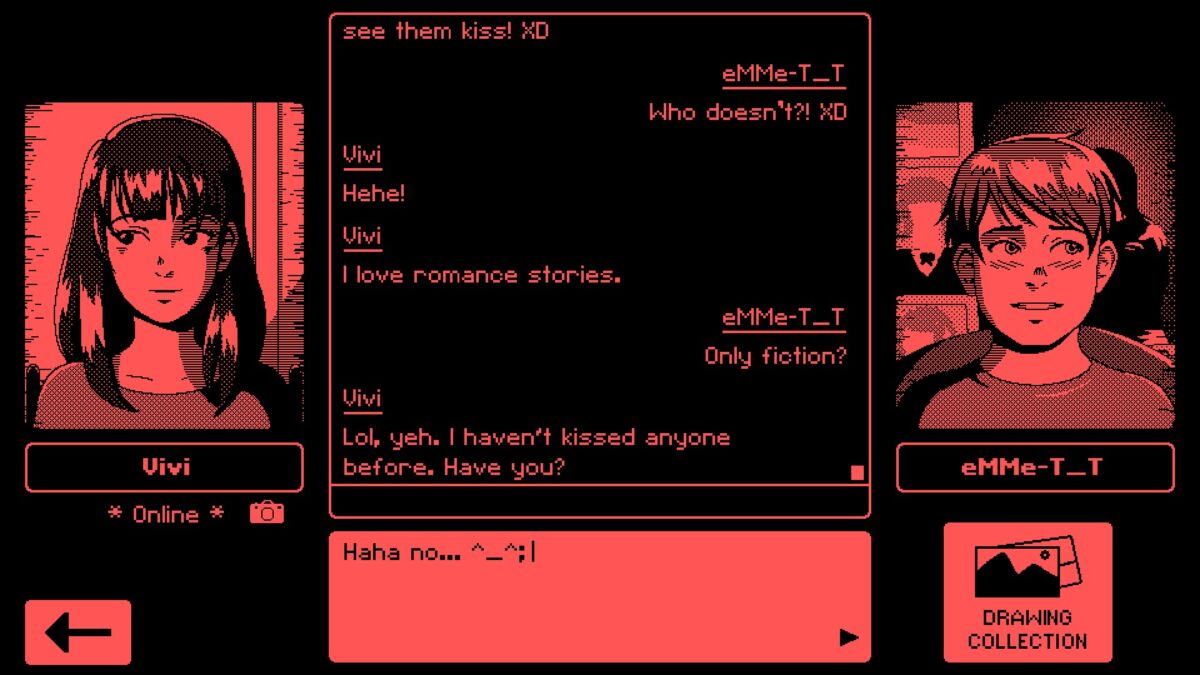

This simulated social network usage forms the bulk of the gameplay. In a slightly modified visual novel format, you interact with characters in this online space via liking, reporting, or commenting on their posts. You also view the homepages of your friends and share more intimate interactions with them in private messenger.

Videoverse’s cast of characters are really worth getting to know. Beyond the cast of side characters that help make the game world feel so full, there are a select few that Emmett forms a real significant connection with. MarKun666 is a sincere, heart-of-gold kind of friend. Certified mad lad Zalor offers Emmett his bombastic brand of ‘girl advice’ while he navigates his own rocky e-relationship. And then there’s Vivi, an enigmatic and talented fan artist who incites Emmett with her posts to the Feudal Fantasy forum.

Just as Emmett starts to overcome the trolls which threaten to challenge his digital utopia and as the relationship between he and Vivi starts to deepen, it’s announced that the Videoverse servers are to be shut down. This planned obsolescence of Videoverse and by extension the Shark paves the way for Kinmoku’s upcoming console, the Dolphin. It’s a development that threatens to isolate Emmett entirely from the vital bonds he’s formed in this online community. While low-stakes on a grander scale, the countdown to the platform’s discontinuation has an oddly heavy doomsday clock energy. It’s somewhat fitting though, as Emmett is having an entire part of his world wiped without a single trace left behind.

I couldn’t help but feel Emmett’s loss. I would miss Videoverse too. Developer Lucy Blundell has crafted an excellently reactive facade of an early 2000s social media platform with all the era-appropriate, cringe-inducing references and emoticons in tow. Banner ads and magazines displaying in-universe game releases help to build the world, as does the customizability of your homepage.

In addition to text posts, members of the forum can also put up digital drawings à la Miiverse. Each user has their own distinct drawing and handwriting style, which is such an endearing detail. The content of the text and image posts on Videoverse had me seriously guffawing at points, like real honking laughs. Maybe it’s my personal appreciation for cringe and anti-humour, but the inclusion of such thoroughly unfashionable slang and memes just tickled me.

Videoverse delivers a strong story even independent of the nostalgia factor. The game manages to touch on raw subjects so thoughtfully, in particular excelling in its representation of disability and internalised ableism. Meanwhile, many of the smaller players in the Videoverse community have their own branching and interlinking subplots. As the narrative processes, Emmett can guide his friends through their struggles using the various ‘words of wisdom’ he takes from fellow Videoverse users: simple little aphorisms like “it really is okay to cry”. He keeps these tips logged in a numbered list in a notebook on his desk — which is just exceedingly adorable.

I’ll admit the art direction of Videoverse had me conflicted initially. Cutscenes of Emmett’s life have got this sort of sparsely-rendered, westernised anime style that you’d see all over DeviantArt back in the day. Though upon reflection, it works well, even just on a self-referential level: it’s as if Emmett is represented in the style of a early 2000s JRPG fan artist you might find on one of Videoverse’s forums.

That being said, the simplicity of this art style translates beautifully to the Shark’s 1-bit graphics. From the bedroom video streams of our protagonist to the dramatic samurai showdowns in Feudal Fantasy, Blundell’s dithering and hatching creates gorgeous depth and visual interest. She has a great eye for pixel art and she employs these key techniques really well. It’s also equally lovely to look at in any of coloured themes you can unlock throughout your playthrough.

Unfortunately, I did encounter a number of technical issues during my time with Videoverse, but this is hardly unexpected for a pre-launch game with such a small dev team. During my eight hours of playtime, I had the game crash four times. Thankfully, a robust auto-save system meant I didn’t suffer from this too harshly. Another problem was a game-breaking bug I experienced resulting from me sending a character one of my drawings before they asked for it. This made that particular save file entirely unworkable, as I was unable to send the drawing again to have the story progress. But again, in this scenario, auto-save came in clutch. These are just small blemishes on an otherwise splendid game.

A Steam key was provided by PR for the purposes of this review.

READ NEXT: 20 Best NES Games of All Time

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.