Scott Pilgrim vs. the World came out about seven years ago, but I saw it for the first time on Sunday. I consider myself a movie buff, so my friends have been constantly harassing me to watch it, and I never did. They were right. It shouldn’t have taken me seven years to watch it. What’s wrong with me? Is there something broken inside that can’t ever be fixed? Why can’t I just show some self-respect and salvage the rest of my life? Am I just giving a vague and disingenuous summary of the internal character arc of Scott Pilgrim?

Anyhow, I have some stuff to say about the movie, and it might be unique because I just had an experience that’s seven years old for most people. Also, it’s interesting to compare with Baby Driver, because that’s still hip to talk about. That’s only been in theaters for about a week, right?

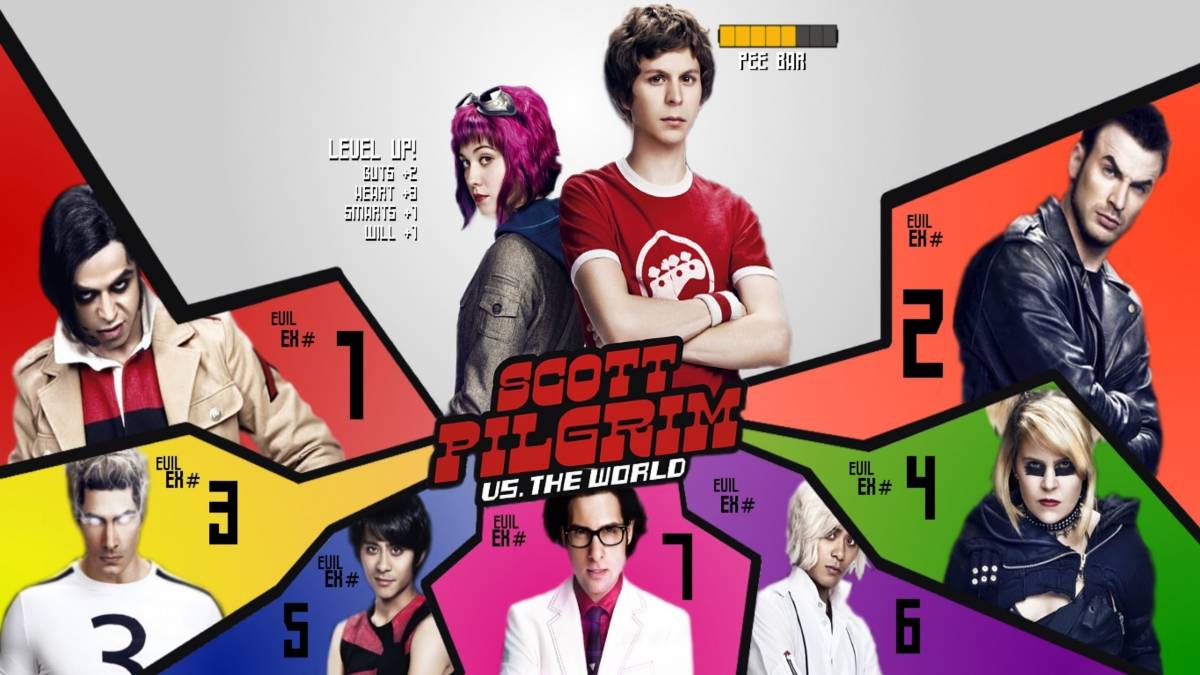

The cast

There’s an awful lot of people in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World whose careers have blown up since 2010. Michael Cera is Scott, the protagonist, and Mary Elizabeth Winstead is Ramona, the woman he’s trying to win over. Supporting characters are played by Anna Kendrick, Brie Larson, Alison Pill, Chris Evans, Johnny Simmons, Kieran Culkin, Mark Webber, Aubrey Plaza, and Ellen Wong. I probably missed a couple.

Currently, it would be borderline impossible to assemble this group of actors and actresses onto a single project. Interestingly, no one ever mentioned the cast to me when they were pitching this movie. They mostly have quirky appearances that stop people from recognizing them. For example, Aubrey Plaza’s character wears glasses, and Mary Winstead’s character dyes her hair garish colors, and that’s really all it takes to make us forget that we’re watching a professional actress and not the character that they’re portraying. It’s extremely basic costume stuff, but the end result is that I never got them mixed up, even though I watched the movie at 3am.

It’s also worth mentioning that Edgar Wright collaborated with Michael Bacall to write the screenplay, an adaptation of a graphic novel by Bryan Lee O’Malley. Michael Bacall is probably better known for the Jump Street movies. Like the cast, Bacall’s profile grew rapidly after “Scott Pilgrim”.

Scott Pilgrim vs. What World?

Edgar Wright doesn’t care about reality. He understands that films don’t need to imitate reality in a literal sense. When you get right down to it, the fight scenes aren’t actually absurd or crazy. People don’t fly in reality, they don’t fight that way in reality, and they don’t have superpowers in reality, but this isn’t reality. It’s a movie. Why would he constrict his ideas by following any rules other than the ones internal to the film? And why should he? “Scott Pilgrim vs. the World” is completely insane, but it maintains immersion because it’s internally consistent. A movie has to be believable, and the key to believability is not realism. Its consistency.

The fights are outrageous, but they’re consistently outrageous. After the first fight scene (which is half an hour into the movie, by the way), every fight is stylistically similar. Total strangers try to murder Scott and when he kills them, they explode into showers of coins, because the movie is structured like a video game. It picks its path and sticks with it, building on top of what it already has, rather than stretching itself thin with too many different tones and rules.

Wright actively sacrifices realism in the name of storytelling. When Scott goes from the living room to the bathroom, then emerges straight into an exterior shot, it doesn’t pull me out of the movie, because it pulls me deeper into the story. A shot of him walking through the living room to reach the front door would have interrupted the story. There’s no story in that shot, so skip it. All the living room shot would’ve added was consistency with reality, but remember: Edgar Wright doesn’t care about reality.

The Weirdness and the People

Scott Pilgrim vs. the World is a bizarre movie, but it works because it doesn’t care that it’s bizarre. It’s not quirky for its own sake, it’s quirky because that’s how the characters behave, and they’re not just quirky. They’re also actual characters. Like, with arcs.

Scott has to battle seven evil people who used to date Ramona in order to have a relationship with her, but he has to conquer his inner struggle first. At the end, he unlocks the power of self-respect and destroys the final villain. He’s got an internal struggle, with his self-loathing, and an external struggle, where he loves Ramona but her exes want to kill him. These two conflicts are interwoven with each other and neither of them can stand up on its own, so Scott’s character arc is tied into everything that happens. Knives also has an arc, and it’s based on her reactions to everything that Scott and Ramona do. Ramona also has an arc, and it’s tied directly to the main plot events. By the way, these characters are also quirky and weird.

What really matters is that there’s a story, and the presence of an actual character-driven story allows the characters to spend some of their dialogue being goofy and adorable. We’re already rooting for Scott when he starts talking. Wright and Bacall wrote everything into this adaptation for a reason, and none of it is pointless. Movies that try to pull off quirky characters, but then fail, are failing because they’re missing the point. Uniqueness alone doesn’t make characters. They’re built through action, through their participation in the story, and all the characters that get screen time in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World do stuff that matters. Scott’s roommate Wallace is unique because he’s an eccentric gay guy, but he’s worth paying attention to because he provides useful information. He foreshadows the confrontation with Chris Evans’s character and supports Scott. He also forces Scott to make decisions when he evicts him. His stack of odd traits is used for comic relief, but it gets to do that because he pulls his weight for the sake of the story as well.

Does it hold up?

Yes. Interestingly, Baby Driver actually felt less developed to me than Scott Pilgrim vs. the World did. Before you get your pitchforks and tell your entire extended family about the freelance writer you all need to lynch because he hates Baby Driver, chill out. I love Baby Driver. My problem is that even though it’s a wonderful movie, and probably the best mainstream release of the summer, it feels like Edgar Wright made it earlier in his career than Scott Pilgrim. The differences are nitpicky and hard to quantify, but they’re based on feeling.

Baby Driver felt choppier in its editing and more formulaic than Scott Pilgrim, which is such a tightly paced and structured film that pretty much every shot belongs in the final product. You can see what I’m talking about in any scene of Baby Driver where there’s some kind of shootout, especially the one where the deal goes bad. The camera whips around frantically and the action is extremely mobile, but it feels oddly cartoony, like things jerk around too much. The action in Scott Pilgrim actually feels more grounded. The action sequences of these two movies are similar in tone, but one of them is an inherently silly movie that’s supposed to feel like a coin-operated videogame, and the other is a crime film. Baby Driver did an incredible thing by existing as a musical that I enjoy, and it had a really neat way to integrate music into the story.

However, with the less original premise and my complaint about the editing, I actually think Scott Pilgrim vs. the World is the better movie. As far as creativity goes though, they both knock the tar out of most of their contemporaries. One of the few movies I like more than Baby Driver is another movie by the same director, which says a lot.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.