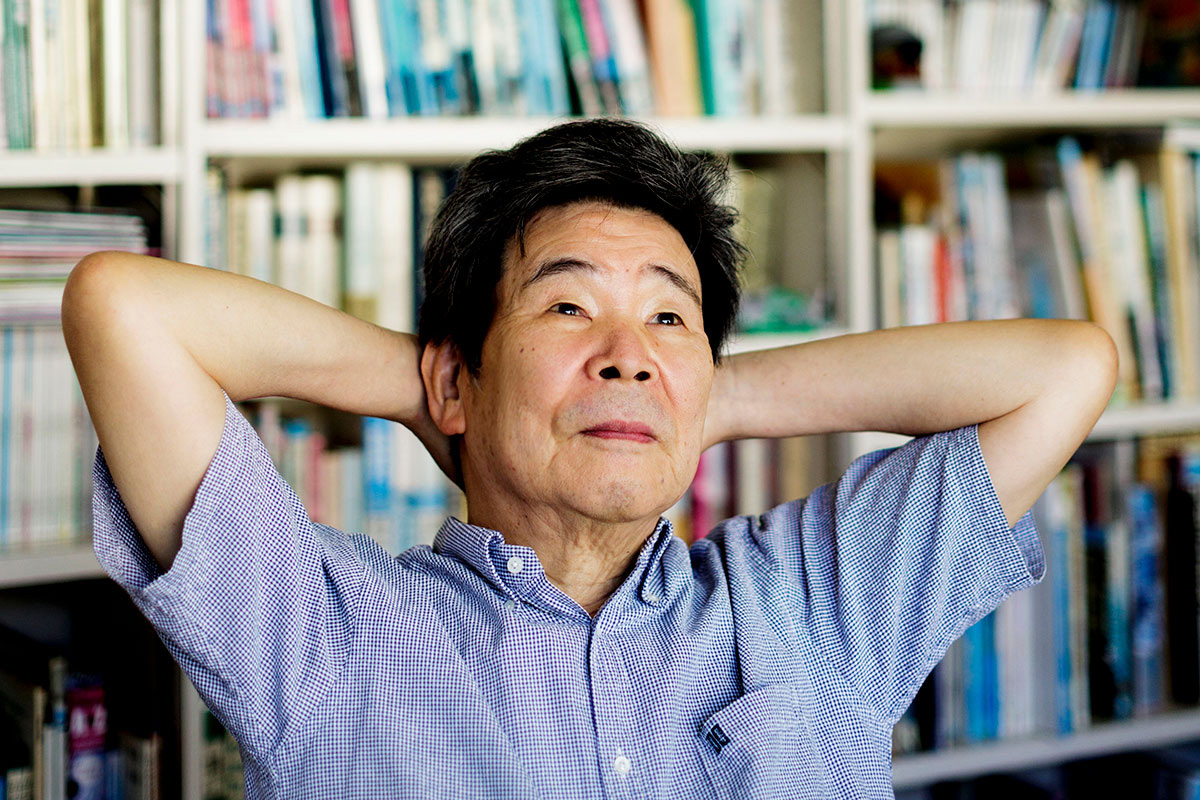

On April 5th, Studio Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata passed away. While both Ghibli and his partner Hayao Miyazaki are practically household names in the West, Takahata has remained a lesser known filmmaker outside of Japan. For years, many of his films were difficult to even see legally in the United States; Pom Poko was not released on home video in the U.S. for nearly 10 years, and Only Yesterday, one of Takahata’s best films, was not released in the U.S. until 2016, 25 years after its original Japanese release.

The reluctance to release Takahata’s films in the U.S. is perhaps understandable, if frustrating. Takahata’s films frequently defy the narrative expectations of those who grew up on Disney-dominated Western-style animation, and are generally geared toward an older audience. Miyazaki’s films, while grounded in Japanese history and culture, are heavily inspired by the West; Takahata’s films are slower paced, less upbeat, and, in general, more reliant upon an understanding of Japanese history and culture. In the world of Japanese animation, Takahata can be considered the Ozu to Miyazaki’s Kurosawa.

Now that much of Takahata’s filmography is finally available in the United States, it is time to rediscover his wonderfully rich and bold body of work. Below is a guide to five of Takahata’s best films.

Where to Start: Only Yesterday (1991)

Only Yesterday is Takahata’s most accessible film for Westerners, and one of his three masterpieces. The story is a simple one that could easily slide into cliché: a woman (Taeko) who lives and works in the city goes on a vacation to the country to find herself. During her trip, she has flashbacks to when she was in fifth grade.

Despite the rather simple premise, Takahata plays with form in interesting ways. The flashback sequences appear in a slightly different, more watercolor-based style than the scenes in the present day, which are more in line with what we expect from Studio Ghibli’s house style. Structurally, rather than only intercutting scenes from fifth grade with those of the present-day, Takahata occasionally cross-cuts the two time periods, making it appear as though the characters are sharing space across the eras. Occasionally the characters literally share the same space, such as when Taeko’s younger self joins the older Taeko on the train she is taking to the country. This unusual structure emphasizes one of the film’s themes: the past is not something that we merely remember, but rather something that travels with us and continues to interact with us in the present in unexpected ways.

The content of the flashbacks also defies expectations. When an early flashback shows the awkward beginnings of a romance between Taeko and a classmate, we assume that a flashback of a lost love will parallel a new romance for Taeko in the present. But this is the only time we see the boy; a lost romance (if it occurred) is never shown. This ties in with the film’s attitude towards nostalgia. The film is in love with the notion of an idyllic past, both for the individual and for the nation, but what exactly that past looks like is fuzzy. Taeko is uncertain what her flashbacks mean; they seem mostly random and are episodic rather than built around a single narrative. Toshio, a farmer Taeko meets, speaks admiringly of the traditional life of the Japanese farmer, but when pressed on why he has a love of these things, he admits that he is just repeating what he has been told. For Takahata’s, nostalgia exists for a past that is fuzzily defined, if it ever really existed at all. This is not to say that his attitude towards the past is nihilistic; the characters eventually do find value and meaning, but they have to find it for themselves in the present, not in an idealized past.

Next Steps: Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

Grave of the Fireflies is certainly one of Takahata’s most well-known films in the United States. While admired, its reputation can be a bit intimidating for newcomers. It is widely regarded as one of the greatest anti-war films ever made, animated or otherwise, but it is also considered a notoriously tough film to sit through. It is often described as a “one-timer,” a film that is brilliant, and must be watched once, but is too painful to sit through twice. This characterization isn’t wrong.

The film is about a teenage boy and his much younger sister’s struggle to survive the Allied firebombing of Japan during World War II. The film opens with the teen’s death, so we know from the start that this is not a story with a happy ending. The film is painful, and is relentless in its depiction of the violence, suffering, human cruelty and indifference brought on by the war.

That said, I think critics do a disservice to potential viewers by painting the film as a 90-minute long slog into human suffering. In addition to pain, Takahata also shows us beauty, love, and compassion here, just as he does in Only Yesterday. Seita’s attempts to care for his little sister, both physically and emotionally, are truly touching. There is a moment early in the film when the two are awaiting news of their wounded mother’s condition and Seita silently performs gymnastics in the background in an attempt to get his little sister to laugh. Later, he teaches her how to catch fireflies and uses the last of their candy to make flavored sugar water for her to enjoy. Even in the horrible suffering of war and poverty, Takahata is a humanist, celebrating our capacity for love and joy. The film is starkly anti-war, and does not flinch when it comes to showing the horrible pain and suffering that human beings can inflict upon one another, but it would be a mistake to only view the suffering in the film. Grave of the Fireflies is a masterpiece because it acknowledges both the best and the worst in humanity.

The Final Masterpiece: The Tale of The Princess Kaguya (2013)

Based on a Japanese folktale, The Tale of The Princess Kaguya was Takahata’s final film. While I would not say it is his greatest film, it is his last masterpiece and well worthy of sitting beside his earlier works. The film tells the story of Kaguya, a celestial being given the form of an infant girl and raised by a poor bamboo cutter and his wife. Eventually the bamboo cutter discovers a stash of gold in the bamboo forest and uses the treasure to buy a mansion in the city and raise Kaguya as a real princess. Kaguya, for her part, resists being taken from the countryside and moved to the city, and is sad to leave her friends and carefree life behind for the comparatively dull life of a lady at court.

The film is similar to early Takahata works in that it privileges the simplicity of country life over the pretensions and affectations of those who live in the city. The princes who attempt to court Kaguya all deceive her in one way or another, and her training on how to become a lady focuses on cultivating an unnatural self (replacing her real eyebrows with ones that are painted on, blackening her teeth, even learning to kneel motionless when so much of her joy in the film so far has been defined by movement).

The visual style is stunning. Using a watercolor-based aesthetic, Takahata does a wonderful job of conveying movement and emotional outbursts through brush strokes. When Kaguya becomes upset, running from the palace and shedding her royal robes in an attempt to return to the country, she is portrayed in a series of blurred brushstrokes, illustrating her desperate desire to return to the countryside in an impressionistic style that makes explanation and dialogue unnecessary. The film is a bit overlong for what is a simple folktale told in an episodic structure, but the visuals are so gorgeous and express the themes of the film to such an effective degree that it doesn’t really matter that the narrative isn’t as strong. It is a work of art with numerous shots that feel as though they could hang beside the masters in a museum.

For the Fans: Pom Poko (1994) and My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999)

The two films Takahata made between his three masterpieces are worth checking out as curiosities, but aren’t the best places to start. Both films are a bit tough to get into due to their episodic structure and lack of a strong central narrative, but they also offer some interesting and bold choices.

Pom Poko tells the story of a group of tanuki (a real animal similar in appearance to the raccoon, but more closely related to foxes) who wage a war against the humans attempting to develop their forest. The tanuki in this film are firmly grounded in Japanese folklore, so they are portrayed as trickster, shape-shifting creatures with magical testicles (yes, really). Similar to other Takahata works, the tanuki seek to return to their traditional ways and save their homeland from Tokyo’s urban sprawl by rediscovering the art of shapeshifting. It is a much lighter version of the same themes of city vs. country and the desire to return to a perhaps non-existent past that Takahata explored in his other works. It is a lot of fun, and has some truly imaginative sequences (a demon parade that the tanuki perform in order to scare the humans is a precursor to some of the surreal imagery Miyazaki would create for Spirited Away (2001)), even if its runtime feels a bit bloated for such a light-hearted, silly story.

My Neighbors the Yamadas has its appeal as well, but is an even looser narrative. Based off of a Yonkoma manga (essentially a four-panel comic strip, similar to Peanuts or Calvin and Hobbes in the U.S.), the film consists of a series of short vignettes that feel like animated comic strips. In fact, Takahata imitated the aesthetic of watercolor panels to emphasize this feeling; because of this style, My Neighbors the Yamadas was the first digitally drawn film produced by Studio Ghibli. As in any vignette-based film, some segments are stronger than others, and watching 100 minutes of 2-5 minutes segments one after the other can get a bit dull. Some of these segments would be great to watch on their own, and the visual style and structure is so strikingly different from the other projects produced at the studio that it is still worth checking out.

Takahata the Legacy

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Ef78Lwd_Ok

In the final moments of his final film, Takahata makes a statement about the thematic concerns that drove his work for the past several decades. In The Tale of Princess Kaguya, Kaguya defends the human world when her celestial family calls it “unclean.” She responds that for all its suffering and grief, the human world also has love, compassion, and a connection to the natural world that gives life value. Whether it is a boy in a warzone giving a candy to his sister, a young woman promising slipping some pocket money to a girl who reminds her of her own selfish youth, or a group of forest warriors dancing and singing every night even as their home slowly disappears, Takahata made a career out of reminding us that even in the darkest moments, humans can help each other to feel love and joy. It is a deceptively simple message, but one we can always stand to be reminded of. I can think of no greater legacy for an artist than that.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.