The underlying vein which runs through the heart of the greatest of Britain’s sitcom heroes is not perhaps the most immediately apparent. What makes a true British sitcom hero is not that bad things happen to him, or that he is frequently the victim of embarrassment, rejection, or derision. It is the more pervasive idea that British people are overtaken by their own expectations and weighed down by those which society desires of them.

The British are not ambitious in the same way Americans tend to be – they don’t covet glamorous women, seek to place men on the moon or grow up thinking one day they’ll be President or Prime Minister. The British sitcom hero has an obsession with social parity, with the need to fit into a constructed niche delineated by certain behaviours which he always fails to meet. For a character to comically resonate with his audience, he himself must be subject to a form of captivity, his ambitions stifled and his needs and desires foiled at every turn.

America, with obvious exceptions such as M.A.S.H., rarely finds itself confined by such deep-seated barriers as the heroes of the British small screen. Fletcher and co. may have been quite literally incarcerated in ’70s hit Porridge, but the structures and social mores which ensnare the British have roots that dig much deeper than the purely physical.

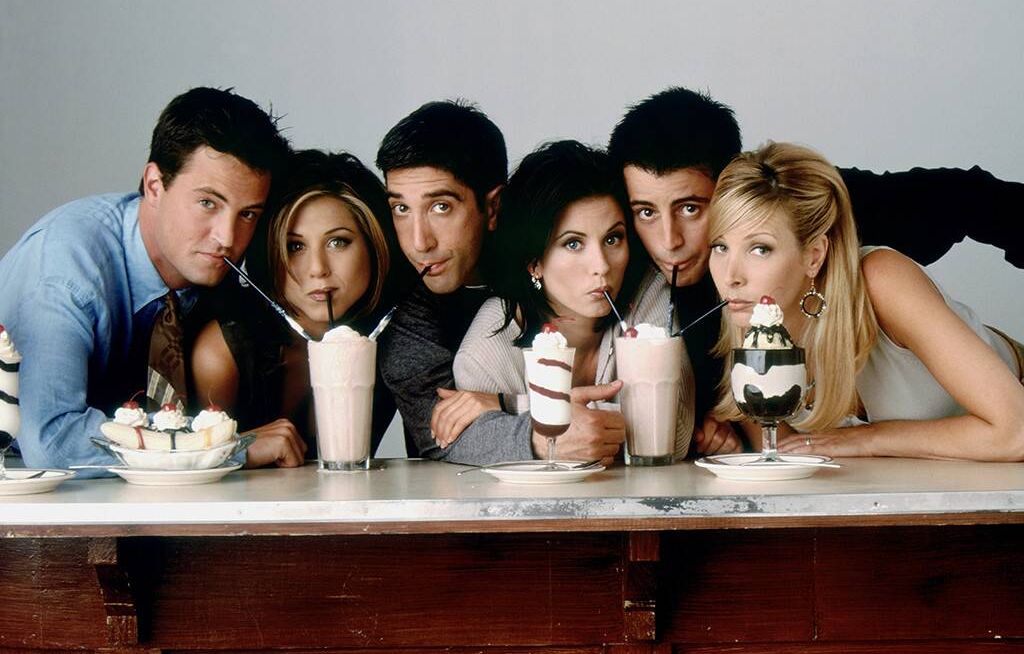

Across the pond, the eponymous Friends navigate the frivolities of romance and the trivialities of workplace dynamics, while the cast of Seinfeld enjoys the freedom to create their own misfortunes in New York. Each group passes freely from one faux pas to the next, the structures that contain these characters so much less pervasive than those which press on the inhabitants of a far smaller, far more neurotic island. If a preoccupation with confinement does permeate across the Atlantic, it usually translates to the traditionally familiar setting of the nuclear American family. From Malcolm in the Middle to Modern Family, The Simpsons to The Goldbergs, each tribe desires freedom from one another rather than the confines of their respective class.

Meanwhile, the standards which dictate the behaviours of the British sitcom hero are social: codes of behaviour, ethical practices, and planes of morality to which our protagonist must aspire but ultimately fail to attain. Failure permeates the British sitcom like a plague, a force that compels the actions of its victims, its irrepressible gravitational pull always overpowering the vain thrust of any attempt at escape. Nearly every British comic hero must crash back to Earth, and the harder he or she falls, the greater the comedic crater.

The framework in which these codes operate is one of class. Basil Fawlty, perhaps the blueprint British sitcom hero, suffers from this perhaps the most acutely. Basil is beset by a desire to see order as befits his desired class, with his sole purpose throughout Fawlty Towers’ peerless twelve-episode run an Icarusean effort to maintain the veneer of decorum to which all hotels aspire. Basil vainly hopes to attract guests whom he considers his social equals, while his attempts to cosy up to his ‘superiors’ only end in embarrassment. Little wonder that the show’s first episode, ‘A Touch of Class’, kicks off the series with Basil trying to improve the class of the hotel’s clientele by cosying up to a grifting landed ‘lord’.

Basil is not alone in his attempts to break from the limitations of his class. Keeping up Appearances focused on the misguided efforts of Hyacinth Bucket to ingratiate herself with a social stratum she perceived as inherently more worthy, her insistence on her surname being pronounced ‘Bouquet’ a doomed attempt to instil a sense of continental pedigree to which she was never born.

Hyacinth, like Basil, suffers from the same warped delusions around her identity, the comic irony of her own self-perception as ripe for comedic mining as her desperate attempts at social climbing or her desire to retain a veneer of social respectability in suburban middle England. Keeping Up Appearances’ extraordinary international success sounds counterintuitive considering its obsession with a peculiarly British preoccupation, but the show clearly fed into prejudices about this quaint little island in which international audiences were keen to indulge.

A desire for social acceptance permeates across characters and across generations. Fawlty and Bucket are perhaps more sympathetic depictions of misguided social climbers carving out their own respective cultural niches to ingratiate themselves with the higher echelons.

Steve Coogan’s Alan Partridge, meanwhile, is a more directly cutting commentary of the sort of middle-Englander who covets Lexuses (or Lexi), describes sex as “intercourse” and thinks that Wings are “the band The Beatles could’ve been”. Tasteless, artless, and small-minded, Alan is less aspirational in his outlook, far more entrenched in the lower-middle-class miasma than his comic counterparts who strive towards societal ascent.

The humour of Partridge derives from the delusions intrinsic to the class which he belongs, the misguided prejudices and behaviours satirised by Coogan and co., evoked by the sort of person who receives all of their information from the Daily Mail and Top Gear Magazine and is incapable of interacting with workmen, hotel staff or members of the opposite sex without placing his foot firmly in his own mouth. Partridge, like the others, is doomed to his fate, but it is his unique obliviousness to this fact that renders him such a distinct tragicomic icon.

Edmund Blackadder, meanwhile, is a classic victim of the English class system. England’s rich history of perpetuating class boundaries, be they those of Medieval Feudalism, the Elizabethan court or the engrained social perimeters of the Regency, are ideal proving grounds for a more potent form of confinement. Blackadder’s comedic troubles stem from the slings and arrows that arise from the socio-historic periods in which he is incarnated.

The whims of a tyrannical Queen who is either bankrupting him (‘Money) or threatening his execution (‘Head’) render Edmund helpless, as do the fatuous wishes of his dim-witted Regent three-hundred years later. Little wonder Blackadder often uses fatalistic language in his miserable lamenting: as he puts it “the Devil vomits into my kettle” or “farts in my face once more”.

Why should these preoccupations with adhering to the expectations of one’s class find such fertile ground on British soils? Britain is hardly the sole country to have created historic structures that elevate the unworthy and burden the disenfranchised. The British comic hero’s desire to escape his social tranche or his fear of failing to meet the standards of his class aren’t born simply because the structure exists in the first place, but because there are some uniquely British pressures that could cause unique levels of embarrassment and shame.

The culture that emerged in England following the Second World War was paradoxical: despite the decline of the Church in British life, Protestant values of respectability, hard work, community and sexual propriety permeated society like water through sand. The need to be ‘Keeping up Appearances’ in suburban England became entwined with a raft of expectations surrounding ‘English’ behaviour, especially concerning the middle-classes: Partridge, Cleese, Brent, Bucket, Corrigan, Hacker, Brittas, Meldrew, all suffer because of the circumstances of their birth.

This desire to fit in not only motivates much of the British comic heroes’ actions, it’s also the root of much of their unhappiness. Hyacinth is too concerned with one-upping her neighbours to even think about giving her belittled husband Richard a peck on the cheek – as ever, the desire to maintain propriety only creates further miseries and informs the behaviours of many of Britain’s most endearing comedic creations.

John Cleese’s revelation that Fawlty Towers was inspired by the idea that “a Presbyterian is someone who has a nasty feeling that somebody somewhere is enjoying themselves” is particularly revealing. Basil’s Protestant values have only driven him further into the mire, trapped in a loveless marriage and desperately sexually repressed, Basil becomes censorious to remain respectable because, according to Cleese, “he can’t imagine himself outside of the system.”

Sexual repression, propriety and conduct are thus the markers by which a man denotes his class and national pride. In ‘The Wedding Party’, Basil’s overriding fear that his clientele might be engaging in sexual activity causes a near-meltdown. As Cleese explains: “if people aren’t getting enough sex, they tend to get censorious of others…a sort of envy disguised as disapproval”. Basil’s “deep Protestant values and tremendous belief in the class system” lead to an abhorrence of the fun he secretly craves but has vainly denied himself.

More recently, a diminishing obsession with class has been replaced with a more general binarism of being part of the social herd. More contemporary comic creations, predominantly those from the 21st century, desire acceptance from society itself rather than from any specific tranche. David Brent, The Office’s bungling middle-manager, epitomises a man whose own self-perception is always at odds with the man he actually is, his wish to be seen as a “friend first, a boss second” and, “an entertainer third” revealing someone always trying to ingratiate himself into a society into which he doesn’t belong.

The genius of Brent’s tragi-comic persona is that it is motivated from a place of insecurity, his ego always latching onto what it considers will bring it the popularity he craves. David belittles others to ingratiate himself with narcissistic bully Chris Finch, makes crass jokes and undermines his superiors to gain the approval or acceptance of a group with whom he is ultimately out of step.

Peep Show’s Mark Corrigan, meanwhile, constantly reveals his deep-seated fear of expulsion from the herd through his relentless internal monologue. Like Basil, he cannot imagine himself “outside of the system”, except that this is now a system relating to the very fundamental nature of humanity rather than a given class. Mark’s cohabitee Jez, meanwhile, might be more successful in navigating the pitfalls of ordinary social interaction, but falls short where Mark finds some degree of success. Jez lives in a fantasy world of delusion, dependence and arrested development through his incapability to face up to the fact that he isn’t, in fact, the world’s most talented musician.

Mark’s failures at living up to his own expectations only perpetuate his feelings of disillusionment and disaffection, his endless litany of broken relationships, work-related fuck-ups and setbacks at the hands of an unforgiving 21st Century reinforcing his viewpoint that this must be his fault. A revealing line from Season 2, in which Mark attempts to impress Sophie by attending a hippy dance class, explains his desperate struggle to fit in, a struggle which only brings him further from acceptance: “if I want to act relaxed, it’s going to take all my cunning, skill, and concentration”.

Mark’s emergence as one of the most beloved sitcom characters of his generation confirms a transition away from the British sitcom hero as a figure obsessed with fitting into a class but rather attempting to assimilate with humanity itself. Mark, like many of this troubled and confused generation, constantly vocalises his anxieties about himself, his flaws, his insecurities and how others perceive him. In the post-Radiohead, social media age of anxiety, Mark’s existential dread resonates strongly: “How do I feel? Empty? Check. Scared? Check. Alone? Check. Just another ordinary day”.

British sitcoms thrive on the understanding that comedy is merely tragedy wearing an amusing hat. While we may enjoy seeing our heroes attain that which they desire through great effort and sacrifice, we scratch a similar comedic itch by having the heroes of our sitcoms fail to meet the rigid expectations of the British class system.

Feeding anxieties of sexual propriety, decency and the façade of social interaction only magnifies these rich comic themes about which British people seem to hold a peculiar obsession. The British default mood is one of uptight pessimism, existential dread and social unease. Little wonder we’re often considered to be so funny.

READ MORE: 15 Best British Comedies Of The 21st Century

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.