Comedy, and animated comedy in particular, is no stranger to working with unsympathetic protagonists – but whereas the likes of Basil Fawlty and Rick Sanchez let their awful personalities out to play in the form of grandiose antics, BoJack Horseman is a very different beast. For reasons beside the obvious. BoJack’s sins are, most often, committed calmly and quietly, so much so that they become just part of the natural course of events.

Unsympathetic is perhaps the wrong word, particularly for a lead like BoJack. He may be a wealthy actor, but most people could see something of their own lower selves in him. And, yes, a lot of the time he’s that special version of cynical that can pass for being the only sane person present – putting him on the same level of more-aware detachment we enjoy as the viewer. But even given all of this there’s no escaping the fact that sometimes, he goes beyond simple half-cut lethargy and does genuinely messed-up things – and this latest season isn’t remotely afraid to confront us with that.

The most prominent one this time around isn’t even a new development – it’s Diane finding out about the time back in season 2 when BoJack nearly slept with a 17-year-old. Rather than this being a simple retread of an old plot, it’s key in terms of audience sympathy. We knew this had happened, and now that particular chicken has come home to roost. Do we now judge him for it, now that others are judging him for it? Seems a bit of a sop, don’t you think?

Appropriately enough, the reveal comes in this season’s #MeToo-themed episode, which also sees BoJack undergo a magical transformation into a leading male feminist by appearing on a talk show and doing nothing else. (The phrase ‘virtue signalling’ has been thrown around and abused a lot since it was coined, but this is a dead-on example.) His entry-level talking points are lifted wholesale from Diane, but plugged into his more media-friendly mouth – and so, like all those who live by the sword, he eventually gets out-feministed by an even bigger poser.

(There is, of course, no reform of the film industry’s attitude towards sexual misconduct. The show is, after all, grounded in realism – and while it’s a fantasy, it’s not that sort of fantasy.)

The combination of BoJack’s resultant guilt/self-hatred, the fact that like two million other Americans he’s now abusing opioids, and his increasing inability to tell the difference between his TV show and real life, ultimately leads him to completely wig out and assault co-star Gina (Stephanie Beatriz, of Brooklyn 99, playing a woman who keeps getting cast in cop shows). The event itself is dark – but darker still is the subsequent coverup, reluctantly necessary for Gina so as to not irrevocably taint her career.

Part of what keeps the show as a whole palatable is its supporting cast, all troubled in their own way but none quite as fucked-up as BoJack – strong enough that the main man takes a bit of a back seat for the first half of the season, in favour of a series of spotlight episodes with the wider plot revolving in the background. By now we know them well enough that looking deeper into their lives seems natural, and it’s kind of a relief that it isn’t as pitch-dark as we can expect from this show – particularly Todd (Aaron Paul, doing the Aaron Paul voice) and his adventures in love and business, both of which quickly become bawdy farces.

When BoJack finally steps forward, though, it’s a no-holds-barred experience – it’s an entire episode-long soliloquy, just us alone with his psyche, as he delivers the eulogy at his awful mother’s funeral because they’re not even close to pussy-footing around here. I’d say it only hurts when you laugh, but it’s not that kind of comedy, or even that kind of episode, more an introspective halfway mark. All things considered, and without wishing to dismiss the supporting cast, this is by far the high point of the season, and Will Arnett, excellent as BoJack anyway, is on absolutely top form.

The supporting cast are strong performances of their own, but their real strength is that – contra BoJack’s boozy star-studded dreamland, and despite the fact half of them are talking animals – they’re firmly grounded in realism, and beyond that, areas of society who don’t tend to get a look in in the media. This series is no exception, and uses this to its fullest, covering plotlines like Princess Carolyn trying to adopt a child as a single woman – and, over the course of meeting with women who want rid of their children, returning to her grim hometown, that recurring nightmare of most Los Angeleans.

Elsewhere, Todd – openly asexual – is dating another asexual. Granted theirs is a demographic which, as the show notes, is a fraction of a fraction but is still out there – and given the grotesque attitudes towards sex in Hollywood and elsewhere, becomes more and more sympathetic as an outlook with every leering underwear advert. Diane takes a trip over to Vietnam while being Vietnamese-American herself – part of a wider demographic whose most prominent recent representation was something called ‘Crazy Rich Asians‘ – leading to all sorts of hilarious misunderstandings when other Americans start talking to her loudly and slowly.

Diane’s character probably has the potential for controversy, given that she’s voiced by Alison Brie – a woman so white she has a kind of cheese in her name – but as she’s not putting on a ridiculous voice there’s unlikely to be any Apu-grade backlash. Still, at least some of the BoJack production staff are probably nervously ticking off the days until someone makes something of it.

Given this, it would be wrong to call the cast ‘diverse’ in the classical sense (to say nothing of the more recent sense, which appears to simply mean ‘non-white’) – but when it comes down, the show is presenting one of the most genuinely mixed bags of recent years, if not in terms of demographic then at least in terms of mindset and neurotypes. Though it’s curious it took a cartoon full of talking animals to do so.

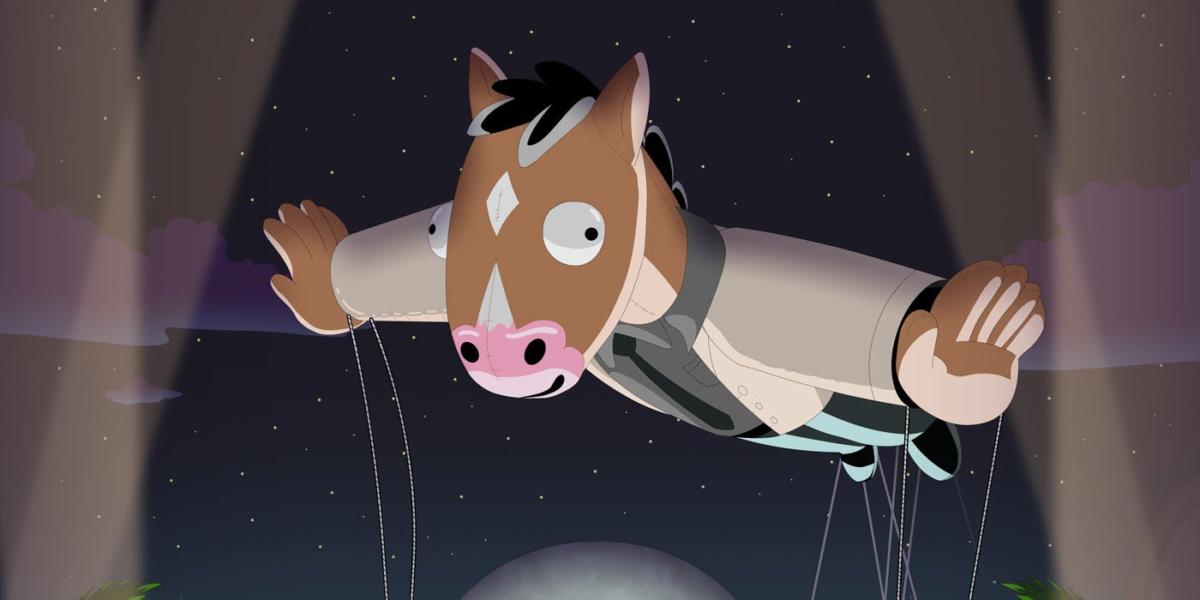

Show-within-a-show Philbert is used, as so many in the genre are, as some fairly blunt metacommentary on the show in which it takes place, though this is an excellent use of the trope, particularly when BoJack breaks down enough that he can’t tell which one’s real anymore.. It’s hard to imagine creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg isn’t excising a few demons of his own through its utterly charmless head writer Flip (Rami Malek, with all the self-hatred he should have brought to Mr. Robot) – that, or taking another dagger to an old media grudge.

Philbert doesn’t necessarily take the prize for metacommentary, though – one episode, delivered through the accounts of a therapist and an arbiter (sworn to secrecy about it all, just doing a dreadful job of it) explicitly characterises Todd’s story as a lighter, fluffier B-plot counterpoint. They don’t say ‘Todd’, of course, they have to use stand-ins – stand-ins so transparent, such as ‘Bobo the angsty zebra’, that they eventually figure out they’re talking about the same people.

A recurrent theme in analysis (at least in mine) of modern adult animated comedy, particularly those entries which, like BoJack, are self-consciously ‘dark’, is whether it successfully walks the line of being grim enough to make people take notice, while still giving the audience a reason to care.

(There is probably room for an animated comedy that goes full-throttle nihilistic, but it would need to be made with greater care than phoner-inners like Seth McFarlane – or, it grieves me to say, the Matt Groening of 2018 – could offer.)

And as such, after a season’s worth of reminders of horrible things past and more horrible things in the present, after being denied the catharsis of any actual punishment for misdeeds and forced to just try and come to terms with it alone, BoJack does what would be unthinkable for most fun drunks and actually goes to rehab. It’s Diane’s idea, of course, but it’s still about the biggest hope spot they could have managed by then. And it is a relief to have an animated show, in this day and age, simply allow a moment like that to be, rather than immediately attempting to riff on it and thereby cutting it off at the knees, utterly crippling any emotion it might have borne.

Still, let’s not be mistaken into thinking that the next season will now be BoJack, fully recovered, learning important lessons and going on wholesome adventures. (There will surely be a next season – the Horseman’s star is on the rise, and it now one of very few shows to reverse the usual trajectory and make the jump from Netflix to broadcast television.) Sobriety is no cure-all – there’s an old quote variously attributed to Jimmy Breslin and Oscar Levant, along the lines of ‘when you stop drinking, you have to deal with this marvellous personality that started you drinking in the first place’. And BoJack is the type to, after a few dry days, chisel that into his forehead.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.