A Total War Saga: TROY is a standard Total War experience with a solid core formula and gameplay loop, though its stagnant and minimal innovation squanders its potential. With this installment, Creative Assembly reaffirms that it’s truly a AAA strategy game developer and business with all the good and the bad that that entails.

The Total War series and its spinoff Saga series, which TROY is a part of, are 4X strategy games with a turn-based campaign strategic layer where players focus on diplomacy, territorial conquest, resource management, research, and city development. When two hostile armies meet on the campaign map, players will transition to the real-time element of the game, where they deploy troops from their armies onto colorful and varied maps and do battle. At its core, TROY continues this well-established formula as it provides a large variety of options to the player for approaching the development and expansion of their empire or faction.

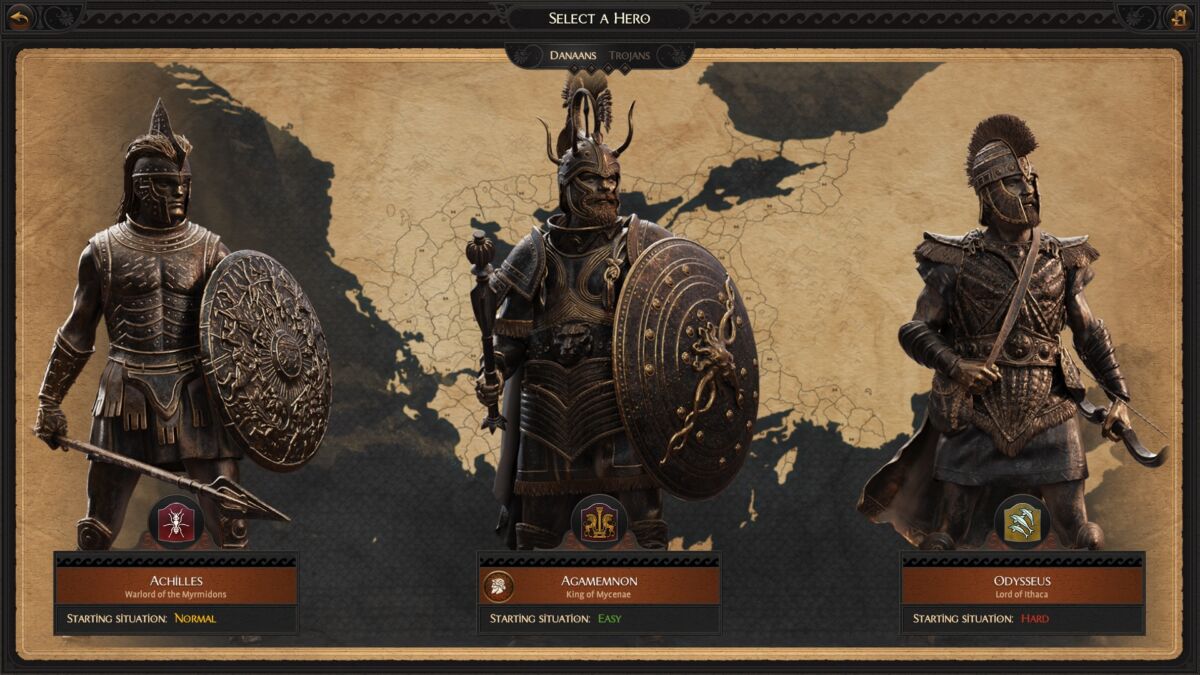

There are two main modes available at launch: custom battles and campaign. Custom battles allow players to choose from a variety of factions, compose their armies with a set amount of funds, and fight battles without any campaign strategic context on any map of their choosing. The campaign mode is the centerpiece of any single player mode in the Total War franchise and this time the game is set during the mythical Homeric Trojan War (roughly 13-12th centuries BCE) where players choose from a roster of eight heroes split evenly amongst the Achaean and Trojan Alliances. On a basic level, the campaign works as intended and will provide potentially hundreds of hours of content to play through.

The first of many major issues with TROY arises with its modes, specifically the lack of any kind of multiplayer at launch. This is the first Total War game to launch without multiplayer for either battles or campaign, which is an egregious and inexcusable major feature strip for the launch of a Total War game. I’m aware that multiplayer will be added nearly three months after, but this only begs the question of why the game wasn’t delayed to avoid such a criticism, as well as work on polishing several of the other issues with the game and adding even more content.

The aesthetics and art direction of TROY are the biggest positives of the game. Since the Trojan War mythologically occurred at the end of the Bronze Age, it gives the visual artists a lot of room for creativity with units ranging from plain and basic to wacky, weird, and downright impressive. Ancient Greek pottery motifs, colors, and styles appear throughout in loading screens, mission and event screens, and the UI itself. It’s a pleasure seeing the Bronze Age come to life so vividly

The victory conditions of TROY’s campaigns are split into a shorter narrative-driven Homeric victory, and a Total War victory, where players conquer the game’s world. These objectives are pretty standard fare for a Total War game and are perfectly serviceable.

One of the most important parts of the campaign is resource management and in TROY the traditional money economy has been replaced with an expanded multiple-resource cash system, which includes food, wood, stone, bronze, and gold. Each resource can be used for a variety of tasks such as unit recruitment, sacrifices to the Olympian Gods, construction, or trade. This is an interesting and thematic development to Total War’s economic system, adding some depth to strategic planning and resource management as most Total Wars have relegated special resources to bonuses for trade income.

However, just like many features in TROY, this resource management system is not taken far enough and is only a minor innovation for the franchise. Bronze production is too simple and doesn’t reflect the period, with copper and tin being vital missing components to the system. Gold in the game is mostly finite, as it’s dictated by a deposit system, which adds an element of scarcity and sustainability to resource management, but it’s odd that this system wasn’t applied to other resources like wood or even bronze.

Diplomacy is another minimally updated feature in TROY, with several elements borrowed from Three Kingdoms, like the deal gauge and region trading. The developers made a clear commitment to make alliances more vital to victory and the gameplay experience as several Epic Heroes have mechanics directly tied to alliances and vassals. Unfortunately, these features don’t go far enough in making alliances truly relevant or reflective of the period, since there aren’t enough direct ways to influence the AI. Puzzlingly, the developers chose to have some characters have no mechanics to alliances.

The mechanics that are present, like Menelaus’ Call to Arms, Hector’s Assuwan League, and Agamemnon’s Lion’s Share, are, on paper, really good and make alliances more meaningful. Unfortunately, the developers chose to arbitrarily section off these interesting mechanics into specific characters, which limits the scope of impact of these new innovative mechanics.

On the notion of characters, Epic Heroes are the mainstay of the campaign and the narrative setting. Each character has unique traits, bonuses, and features that theoretically make them stand out and make each playthrough unique. Epic Heroes and Heroes (basic generals) can equip items and level up using personalized and extensive skill trees to customize their role in battle and the empire, much like in the Warhammer series. Granted the level of customization and depth of skill trees isn’t comparable to Warhammer, but what is present is functional.

One way CA attempts to diversify and characterize both the Homeric Trojan War and the Epic Heroes is through the narrative-focused Epic Mission quests. And just like most things TROY, there is a decent variety of Epic Missions on a basic level that give insight into the different characters as well as their Homeric path. However, there’s a critical flaw in the technical implementation of these Epic Missions because they are potentially game breaking and will completely lock off the Homeric victory condition if players aren’t careful.

In Total War: Warhammer, there is a system in place where if the conditions for a quest are impossible to reach, the quest will automatically proceed to the next stage. While playing a Menelaus campaign in TROY, I witnessed a game-breaking situation where I activated an Epic Mission quest that required me to be present and at peace with the owner of the Cretan city of Knossos. By that point, I had already conquered Knossos and eliminated the original owner, so I wasn’t able to make peace with the owner of the city. The result was that the game couldn’t recognize and proceed with the quest as one of the conditions was impossible to meet.

This is the first Total War game that I think the compartmentalization of features to each hero hampers the developers goal of diversifying the game. For Warhammer it makes sense that each character and race is a kind of specialist in their field and the character’s are designed differently enough that it works. In Three Kingdoms, despite the homogenous setting of each character closely-tied to Han China, the characters felt that they were part of a grander whole, but also unique enough due to small but meaningful mechanical differences to make each playthrough interesting and enticing.

In TROY, I feel that CA is forcing mechanical and feature diversity on the characters and factions, sacrificing innovation and development of the entire series in the process. I also think that the period and scope they chose hasn’t made their job easy, because in the Iliad, despite there being a conflict between ostensibly two different cultures, they happen to follow the exact same pantheons and the characters in relatively similar ways.

I think it’s fine to have a game dominated by a more homogenous cultural period. We see this done quite well in Shogun 2 and in Three Kingdoms. The diversity and beauty comes from the inherent detail and character of individual factions and heroes, rather than a developer forcing game mechanics awkwardly as character and faction definers. To sum up, it’s as if CA is forcing the game into the characters and the historical period rather than the characters of the setting guiding and inspiring development.

Heroes and Epic Heroes will command armies on the campaign map and during tactical battles. Each major faction has a relatively extensive unit roster, focusing primarily on various types of infantry as cavalry and war machine units were a rarity during this period. The rosters have some overlap with common units, but generally each faction has a decently defined tactical doctrine, such as clubs and heavy infantry for Mycenae or skirmishers and ambushers for Ithaca. Mythical provide limited but unique and thematic options for players to complement their army builds or supplement some of their own weaknesses.

Ever since the release of Total War: Warhammer, the army traditions feature has been stripped from Total War games and is sorely missed in TROY and the series as a whole. Traditions served as a way for players to directly invest in the survival and success of their armies, as well as on a strategic level providing more options for synergy and decision-making in managing armies.

In addition, the Supply Lines feature is still present in TROYwhere the cost of maintaining armies increases exponentially based on a percentage per army. This feature is frustrating and annoying as it limits player options in how they want to approach army management and conquest. Army caps in Three Kingdoms worked better.

The last major feature unique to TROY’s campaign is the Divine Will mechanic where players can build temples and pay resources to offer sacrifices to one of the great Olympian Gods for their favor to provide powerful boons and grant access to mythical units and Epic Agents. The Divine Will system provides a decent enough dimension of strategic decision-making for players to come up with effective synergies for their characters and armies. Disappointingly, two of the major Olympians, Artemis and Hephaestus, have been left out for the time being.

Royal Decrees (the technology tree), building management, character skills and the Divine Will system all have common issues that are present in TROY but also the Total War franchise as a whole. The two main issues are the blandness of upgrade design and the resulting meaningless decision-making. One of the many strengths of strategy games is the complexity of cause-and-effect relationships found in player choice and interaction. There are opportunity costs, benefits, and detriments to every decision and meaningful choices come from the relevancy and cost-benefit consideration of an action. Choices and decisions, in essence, become meaningless when a player presses any button and achieves a positive result of some kind, regardless of careful consideration and thought or not.

In TROY, almost anything the player does gives them some kind of benefit, most of the time a substantial one without significant penalty. Time and money in recent Total Wars in most cases, I would argue, are not made relevant enough of a cost, or in other words, the cost doesn’t necessarily reflect the benefit in a proportional and meaningful manner. For example, I can accidentally perform a hecatomb action for Hera without much consideration and all I need to do is wait five turns for the Hecatomb to recharge and I wouldn’t feel much of a loss, because Hera’s benefit from the Hecatomb is still useful in some way even without my intention, or the upgrade is so irrelevant that I wouldn’t even mind having.

The blandness primarily comes from the design decision to make almost everything give positive effects and no clearly perceived consequences from decisions or integrated relationships between different systems. Let’s take the Divine Will and the Olympian Gods once again for TROY. From the Iliad, we know that the Trojan War wasn’t only a war of cultures and heroes, but even a conflict between the Olympian Gods. There is nothing in the game that illustrates this dynamic. You would think that if a player were to give favor to Hera, then it would be harder to gain favor from Aphrodite, for example.

Essentially, the challenge of recent Total Wars comes down to how to best optimize decisions for maximum effect on higher difficulties against a cheating AI, whereas on lower difficulties most experiences will be relatively easy with few moments of meaningful decision-making. Almost every decision will most likely have positive, linear, and simple consequences with little cost to the player and unlikely significant repercussions or consequences from poorly thought out decisions.

Regarding tactical combat, TROY is equally as uneven here as it is with the strategic layer. Field battle map design is bafflingly poor on the whole. There are two main conflicting elements to TROY’s map design: terrain features and map size.

Field battle maps are tiny compared to previous Total Wars (even Thrones of Britannia had larger maps), which limits tactical options for players and the prevalence of cliffs, gorges, and rocks makes the maps feel even more cramped, in effect railroading and limiting battles to choke point slugging matches. Strangely, siege battle maps are noticeably larger, with more expansive city layouts and large deployment areas. But there are also plenty of siege maps that take inspiration from the bland map design inWarhammer with few approaches for tactical choices.

It’s no secret that the Total War series has been plagued by sub-par AI, though this is more of a general strategy game issue than solely endemic to Total War. It’s still important to note that the AI is not very good in TROY and, when combined with the smaller obstacle-filled map design, even more exploitable. I’ve noticed the AI skirmish units running away from a pursuer even after the pursuing unit ceased its movement, or an AI hero just standing around doing nothing near an engagement while their troops get slaughtered. They added minor behavioral improvements from Three Kingdoms, but it’s still in a pitiful state.

In terms of units, since this period was more focused on infantry, the developers put in extra effort to diversify the infantry-focused nature of combat during this period. They did a decent enough job with the different infantry classes and their performance, though nothing ground-breaking as the unit weight classes were always present, but now they feel more distinct in how they behave. The difference between light versus medium is more noticeable than medium versus heavy, though. The rare presence of cavalry and chariots makes their use more impactful, but they are not essential. In fact, the map’s design may impede cavalry and chariots quite heavily.

Siege battles are relatively dull and grindy affairs due to a lack of equipment and combat options throughout the game. This is where history works against some of what made Total War really fun to play. Siege battles are still as weird as they are in Warhammer as all units magically spawn ladders when assaulting walls. In effect, siege battles don’t feel like the heavy and bloody ordeals of preparation and planning as they did in history and are more of an annoyance and grind.

There are two nice additions implemented in tactical battles that introduce increased player control and potential innovation for the future. Some units have dual combat modes, mostly spearmen with shields, where players can command units to swap weapon setups and change unit stats for different combat roles. This is a nice minor addition that can definitely be more widely applied in future Total Wars.

Shields have also been improved and been made more modular in their relation to missile weapons. There are some shields that have up to 85% missile block chance, making said units highly resistant to missile weapons. But these shields are mostly found on the heavily armored and rare elite units and not every faction has them. This modularity of shields is excellent and gives units a wider range of roles and capabilities. Oddly, though, some unit shield visuals do not equate to their shield stats. For example, Spartan Laconian Militia wield tiny buckler shields and get a 40% missile block chance, whereas a Shielded Spearmen unit with a large square shield only has a 50%.

Ranged units with their high rate of fire, range, damage, ammunition, and ease of access to powerful strategic buffs make shields all but useless. You have a decently armored spearmen with a 65% missile block chance and slow? How cute, I have six slingers buffed by Hera and with 180 range. By the time the spears reach the front line they will be combat ineffective.

One of the main design principles CA highlighted in their promotional material for TROY was the “Truth Behind the Myth” approach. As a historian, this approach is really interesting as it entertains the idea that all myth and legend has a basis in truth and it’s a matter of interpretation to bring it to life, as seen in TROY. It’s clear that this design approach permeates the game, but I’m conflicted about its implementation.

If this principle served to guide the art direction and aesthetics, then I’m absolutely all for it. However, when it comes to the mechanical implementation of mythical or fantastical units, as well as godlike powers, this is where the game starts to feel weird. For example, I have no problem with the visual design of the Minotaur, Cyclops, and Giants, but when they perform actions and get into combat, then it just feels odd, because it’s realistic-looking units performing similarly to outlandish Warhammer creatures and monsters. Interestingly, I don’t get the same feeling with the Epic Heroes, but the “monstrous” mythic units are a sore thumb in this regard. Centaurs, Harpies, Spartoi, and Corybantes fit right into the setting, though.

The Epic Heroes do have an issue in this regard when it comes to abilities. There are several abilities that impede enemy units or force them to attack the hero with a taunt ability, which feel and perform fine. But then there are godlike healing abilities, and even the one-use Aristeia heroic ability, which acts like a small heal and short and powerful stat buff, creates an odd cognitive dissonance and raises questions as to why other godlike powers haven’t been included. I can’t credit or knock CA’s design approach with TROY as it is quite literally good, bad, and also odd.

The UI of TROY is generally good in campaign, though a mixed bag in tactical battles. The campaign UI is pleasant and easy enough to read, especially with a helpful overlay tool incorporated from Three Kingdoms. There is some clunkiness in the Diplomacy menu as there is no “back” button and the actual “back” button backs the player out of the Diplomacy screen completely and instead players have to press the “decline” button to end current negotiation to go to the Diplomacy menu. Very strange, but mostly everything else in the campaign UI is solid.

The tactical UI is another story. Most notably, units don’t have banners at all and have generic floating icons on the battle map instead. In addition, the stat tracker underneath the unit icons are straight out of Total War: Arena and they look ugly and low-budget. Otherwise the unit panels and icons are pretty clear and easy to understand.

Regarding performance, A Total War Saga: TROY generally ran smoothly in campaign and in battle on my setup (RTX 2080 TI, i9-9900K). There were some performance and frame drops in a specific situation when dragging the map, while at the same time holding a movement order for a unit. Some unit animations are also odd up close. Most annoyingly, I experienced minor UI and unit command lag, which can impact tactical control.

In terms of bugs, aside from the game-breaking Epic Mission situation, collision detection is off. I noticed AI units running through my own unit when they shouldn’t be able to. This was present in some of the early promotional material and still needs work. Also, as a result of this, charges feel weaker, which is odd considering the engine is used for Warhammer, which has excellent collision detection. Other than some minor clipping issues on maps and unit weapons, I didn’t experience any crashes or other significant bugs.

A Total War Saga: TROY is a big disappointment on many levels: mechanically, creatively, and technically. This reaffirms that a company with the resources to do great things prioritizes safe incremental steps forward rather than not holding back and aiming to push the series, and thus the genre, forward. The potential was there, but TROY ends up being a run of the mill, standard Total War experience and as a customer, reviewer, and player, it’s important to demand more from this venerable series.

An EGS key was provided by PR for the purposes of this review.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.