What do you think of when you think of Disney? Princesses? Plucky heroes? Lessons for kids? What about unspeakable horror? Maybe not. While many admit to being traumatized by Disney films, whether it be the supernatural horror of the “A Night on Bald Mountain” sequence in Fantasia, the body horror of a boy turning into a donkey in Pinocchio, or the surrealist nightmare of the “Pink Elephants on Parade” number in Dumbo, they would not consider horror part of the Disney formula.

However, horror is more than a by-product of their films. It is a vital component of Disney animation, and it has been there from the beginning. From his earliest Laugh-O-Gram shorts, Walt Disney was interested in creating fairy tales for the 20th century. These stories always contain a degree of darkness, danger, and even horror; in his “On Fairy Stories,” J.R.R. Tolkien referred to the setting of these stories as “a perilous realm” where the characters are under “the shadow of death.”

Disney has been accused (by Tolkien, for one) of sanitizing these dark stories. There is truth to this. The animator had to worry about censorship and ticket sales, both of which demand a somewhat lighter touch. Still, horror remains an important part of the Disney tradition. While making comedies, the studio borrowed the cinematographic tools of the era’s live-action horror films, and even pioneered a few techniques that future films would use to create terror and dread in the audience. Below I look at five of Disney’s pre-code, horror-themed animated shorts to see how these techniques were put to use.

The Skeleton Dance (1929)

Disney’s Silly Symphony series of animated shorts ran from 1929-1939. In contrast to the Mickey Mouse shorts, which were produced more rapidly on a smaller budget, the Silly Symphonies were opportunities for the animators to experiment with the art form, practicing techniques that they would later put to use in feature-length films. It is fitting that the first film in the series would be horror-themed.

While Disney did not generally have much trouble with censorship, the Skeleton Dance was somewhat controversial. According to Neal Gabler in Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, theaters were initially reluctant to show the film because they found it “odd and even gruesome” (p. 131), and the film was even banned in Denmark because of its macabre tone.

The film is filled with what is by now cliché Halloween imagery, such as two cats in front of a full moon, an old church graveyard, and skeletons leaving their tombs. The skeletons then form a line in front of the camera and perform an extended dance for the audience. While at heart a humorous musical, the film has its roots in a darker medieval tradition: the Danse Macabre. Becoming popular during the time of the Black Death, these plays would involve skeletons dancing with people as they march to their graves. The dance served as a reminder that death was ever present and could take someone away at any time.

While a bit primitive, the film does have some nice visual flourishes you might expect in a horror film, such as the use of a subjective camera. There is one shot where a skeleton flies towards the screen and the camera travels through its mouth and down its throat. It’s a fun touch and shows you how Disney was experimenting with making the audience feel the animated figures as a physical presence.

Hell’s Bells (1929)

The fourth Silly Symphony film, Hell’s Bells, is a children’s version of Dante’s Inferno. The film shows the various monsters and demons of Hell going about their daily business, which, involves dancing, feeding Satan’s dog, milking the…dragon? And, of course, plenty of torture. You know. A typical Tuesday.

Borrowing the subjective camera of The Skeleton Dance, the film opens with bats and a spider flying towards the camera with devilish grins. A giant snake then appears to eat the bat, swallowing it whole. When the bat struggles in the snake’s throat, its wings push out of the snake’s skin, allowing it to fly away.

Then the demons come in, dancing around the flames, their huge shadows projected onto the walls like the vampire in Nosferatu. At this point the surrealist imagery intensifies. A dancing demon slams into a wall and becomes a cubist representation. A giant devil commands demons to get his dinner, which they do by milking flame from a dragon. He then delights in tossing smaller demons to Cerberus’s waiting mouth. When one of the lesser demons runs, he chases him only to fall into a pit of flames, where the fire shapes itself into hands which spank him.

Salvador Dali called Walt Disney “the greatest American surrealist“, and that title is earned in this short. Even in Dali’s own short from the previous year, Un Chien Andalou, surrealism is mingled humor with horror, and Disney (along with animator Ub Iwerks) takes this mingling to the next level. Surrealism would go on to define a small, but influential strain of horror, perhaps best seen in Dario Argento’s Suspiria. Hell’s Bells leans more heavily into humor, of course, but the imagery is never that far from crossing the line into disturbing.

The Haunted House (1929)

The haunted house film is likely the oldest horror sub-genre, going back to Georges Méliès horror-comedy, The Haunted Castle. The genre’s formula has changed little over the past 120 years: an innocent bystander stumbles into a haunted house, encounters a hoard of ghosts and monsters, and is either killed by them or escapes.

In the haunted house genre, it is not just the monsters who attack the protagonists, but the house itself, which is key in Disney’s The Haunted House. As soon as Mickey enters the house, it begins to attack him. The door locks itself, the lights turn off spontaneously, and when he grabs a door handle to escape, it becomes a skeleton’s arm. Inside the house, shadows take on a life of their own. At one point, Mickey’s shadow detaches from his body and becomes a Grim Reaper figure that chases Mickey throughout the house.

The short even contains a gag that quite possibly influenced the future horror trope of malevolent trees attacking the protagonist. In the film, a sinister-looking tree tickles Mickey, pushing him into the house. I was unable to find an earlier example of attacking trees on film, so this may be the earliest use of the trope in cinema (of course, killer trees have existed in myths and folklore for centuries). Disney would re-use the trope to more frightening effect in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and the trope would be later be used in live action in The Wizard of Oz. Evil trees remain a horror staple in films such as Poltergeist and Evil Dead.

Egyptian Melodies (1931)

Mummy movies, including lost films such as Georges Méliès’ Robbing Cleopatra’s Tomb and The Mummy , were a staple sub-genre of horror during the silent era. Discoveries of the bust of Nefertiti in 1912 and of King Tut’s tomb in 1922 led to an obsession with ancient Egypt, especially its tombs and death rituals, in the West. Disney’s Egyptian Melodies plays into this general obsession, but actually predates the film that you might think directly inspired it, Universal’s The Mummy, by one year.

The film follows a spider as he enters a pyramid and encounters a number of supernatural threats, from dancing mummies to hieroglyphics that come to life. Visually the film is fascinating. It borrows from the techniques of German Expressionism, which would be used heavily by the universal horror film cycle that was just starting in 1931. The short uses canted angles to suggest the chaotic horror of the tomb. When the hieroglyphics come to life, double-exposure makes it appear as though the images are dancing around in the poor spider’s head, terrorizing him.

The film also makes use of a pioneering 3D technique to show the spider descending down long, winding corridors into the ancient tomb. With the camera behind the spider, following him along in an over-the-shoulder Steadicam-style shot, it feels like a much more modern sequence. It is a stunning effect, far ahead of its time, and is Disney’s most effective use of the subjective camera so far. It causes the audience to feel the same sense of anticipation as the character on screen. Here, of course, it is played mostly for laughs, but it would eventually become an important cinematographic technique for horror films such as The Shining, where Kubrick uses the camera to track Danny riding his big wheel throughout the halls of the Overlook Hotel.

The Mad Doctor (1933)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K-JlevnccDk

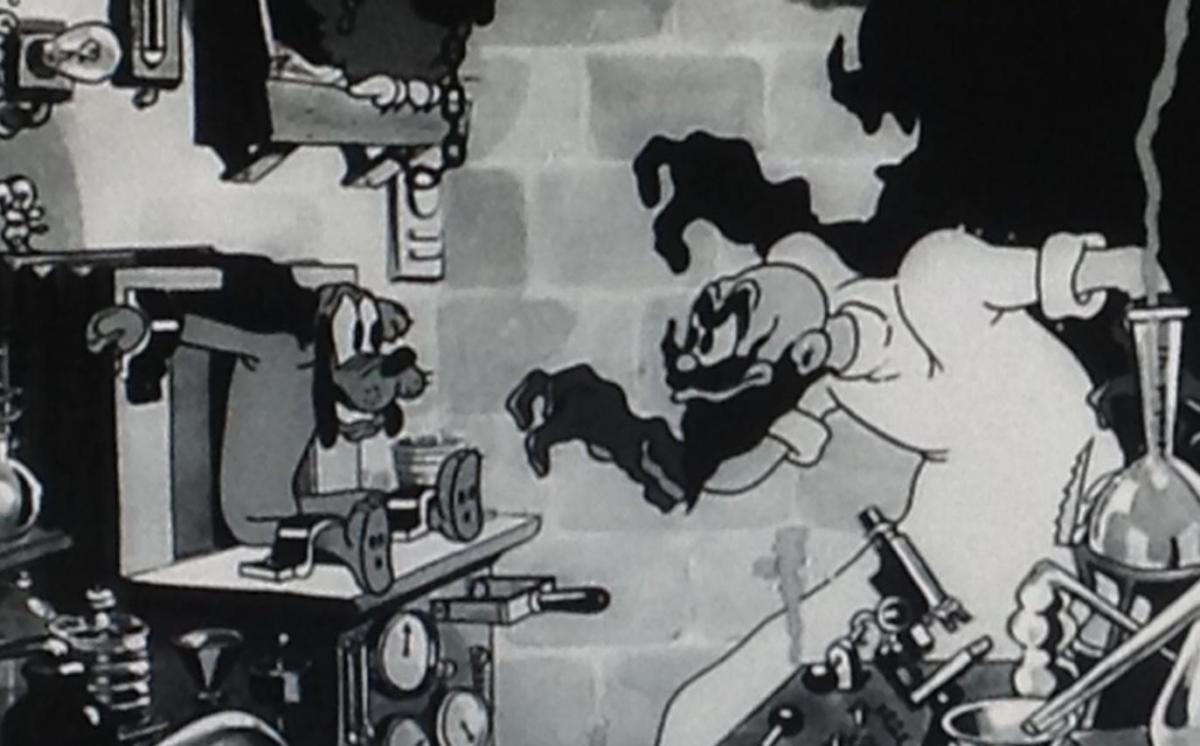

Not as pioneering in terms of technique, The Mad Doctor is quite possible the darkest short ever made by Disney. The film is a standard mad scientist story that was already growing a bit stale in 1933, with films such as The Monster (1925) and, of course, Frankenstein. Even many of the techniques are borrowed from previous Disney shorts; most strikingly, the 3D sequence from Egyptian Melodies is reused with Mickey taking the place of the spider.

It was also Disney’s most controversial film to date. The film was banned in England, and according to Karl F. Cohen’s Forbidden Animation: Censored Cartoons and Blacklisted Animators in America, there are rumors that Walt Disney pulled the film from circulation due to its sadism (p. 25). Additionally, it is one of the only Disney shorts to have passed into the public domain because Disney had forgotten the film to the point that it failed to renew the copyright. That’s right: the film was so disturbing that it made Disney forget about money.

So what made this film so dark? The story involves a mad scientist kidnapping Pluto, which forces Mickey to search for him in the doctor’s haunted castle. The most disturbing aspects of the film involve the doctor’s treatment of Pluto. First, he straps the dog into a chair and, using a chalkboard, explains his plans to give Pluto the old Human Centipede treatment by attaching his head to a chicken’s body. Later, he ties Pluto by his tail to a meat hook and gleefully cuts off the top half of the dog’s shadow with a huge pair of scissors. Mickey is then captured in his attempts to rescue his friend, and strapped to a table where a buzz saw is slowly lowered to cut him in two.

It is probably the most disturbing of these pre-code films. But, of course, all five of these films are primarily comedies and have plenty of fun gags for those with a darker sense of humor. They are also all interesting to view as a lesson in how animation, even animation meant for children, uses, and can even inspire, live-action horror films.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.