One of the few glimmers of hope that we take from the loss of any great icon is having the chance to rediscover their buried catalogues of underappreciated work. Sean Lock’s recent passing provoked an outpouring of feeling so genuine and widespread that it felt as though the country had lost a mutual family member, such was the comic’s uncanny ability to be so gloriously esoteric yet so universally accessible.

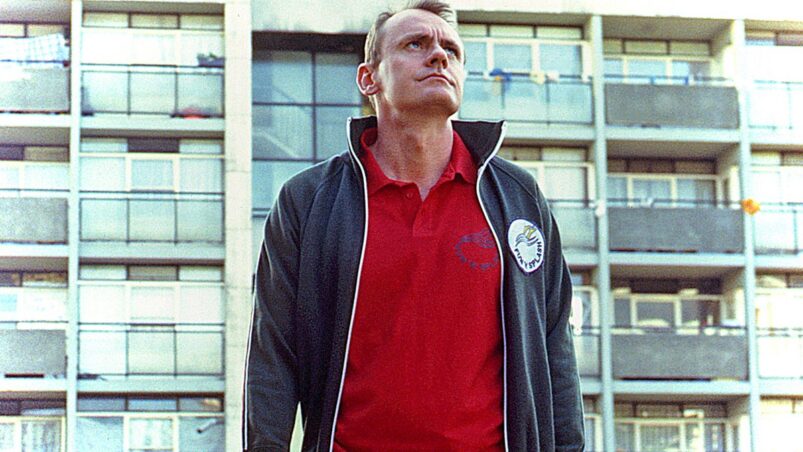

Lock’s panel show ability was legendary, a man who could consistently churn out ideas of unique ingenuity and voice, a one-man comedy factory of invention and wit. It is his little-seen sitcom, 15 Storeys High, however, which shines brightest as the Surrey-born comedian’s greatest comedic legacy, an intimate, bespoke work which reveals so much of the late comic’s glorious comic mind and his innate understanding of the minutiae of British culture.

Originally a BBC4 Radio 4 series entitled Sean Lock’s 15 Minutes of Misery, later rebranded as Sean Lock: 15 Storeys High, the show found moderate success on the airwaves, although one still senses a creation straining to find its true voice, its most perfect iteration. The studio laughter, the constant clunking sound of the lift taking us to another floor of the show’s fictitious tower block, the awful intro music, all were stripped away when 15 Storeys was reborn as a TV sitcom on BBC3. Out went Peter Serafinowicz’s portrayal of sidekick Errol, Sean’s (now Vince’s) docile flatmate, a young Benedict Wong introduced to better embody the submissive, naïve whipping boy who might’ve seemed less believable with his radio predecessor’s six-foot frame.

The show’s transfer to a more mainstream, more visual format expanded its comedic arsenal, a grey filter and some quirky camera positions heightening the sense of urban claustrophobia. Sadly, it failed to find the mainstream traction which contemporary sitcoms such as The Office and Phoenix Nights had enjoyed, with co-creator Mark Lamarr recently stating that his dearly departed friend was despondent at the lack of widespread attention his first full sitcom had achieved. Yet despite its apparent obscurity, 15 Storeys High deserves the same acclaim and adoration as the great shows which cemented the legacies of Gervais, Merchant, and Kay.

Like all great works, 15 Storeys High is the pursuit of a vision. Most sitcoms actively chase their ultimate terminus, every beat designed to arrive at a predestined denouement wherein its converging characters and storylines reach full comic (dis)satisfaction. 15 Storeys, however, is plotted loosely, a show which ambles and meanders towards no particular location, far more interested in taking its time examining character than bolting towards a specific eventual destination. Far less interested in the pursuit of a perfect narrative, the show instead concerns itself with exploring the mundane intricacies of everyday British life.

Vince and Errol’s respective storylines still anchor proceedings, but 15 Storeys High owes a debt to the vignette-laden patchwork of tower block living inherited from its radio predecessor by occasionally refocusing its perspective to the lives of the other inhabitants who share the dowdy confines of the looming edifice. These perfectly pitched vignettes show Lock’s understanding that comedy comes as much from character as from dialogue or narrative, each an intimately surreal window into the domestic mundanity of South London living.

Episode four, for instance, introduces us to a loveless couple whose very postures, listless and languid, reveal their mutual apathy, the languid husband’s complaints that his macaroni cheese should consist of “cheese, cheese, cheese, cheese, macaroni, cheese, cheese, cheese cheese” rather than “macaroni, macaroni, macaroni, macaroni cheese” a perfect evocation of how a stale union can produce such trivial domestic pedantry.

Other vignettes, from an affable salesman being forced to bathe and don and hazmat suit at the request of an obsessive-compulsive tenant, to a wannabe pop manager attempting to groom a group of lads for a failed bid at pop superstardom, evidence a sitcom with a deft hand at exposing the eccentricities and idiosyncrasies of British life behind closed doors.

15 Storeys High’s TV release coincided with a golden age of comedies which examined the nuances of human behaviour over the broader, more farcical strokes of preceding single camera sitcoms, cult sensations The Office and Phoenix Nights defining the landscape to far greater acclaim. Few shows, however, have managed to birth such a diverse array of one-off characters with such immediacy and insight as Lock’s magnum opus.

Such vignettes are born of an intrinsic understanding of the British experience. For all the claims to the suavity of our actors or the prowess of our Olympians, these exports are inherently exceptional. The people who inhabit grim tower blocks, rows of unremarkable terraces or high-rise apartment complexes are rarely populated by Tom Hiddlestones or Alex Peatys – instead they’re crammed with overzealous Christian Bible sellers, middle-aged table tennis obsessives still living with their parents and failed actresses trudging to the next dead-end audition. 15 Storeys High was never afraid to shy away from cold hard reality.

Lock’s gift was to place a surreal twist on such mundanities, to highlight the absurd eccentricities which continue to define working British life, the late comedian’s uniquely surreal comic sensibility shining through via 15 Storey’s very particular use of language. The opening scene from episode four of Season 1 has Vince perusing a recipe book from which he is ripping unwanted pages. “Pork stuffed with whelks, apples, and done in a rabbit’s liver sauce?” reels Vince in voiceover. “That’s surf, turf, orchard and burrow!” And when Vince finds himself trapped in a lift with the object of his affections, he complains that she “swans about like Chris Eubank…farting Wedgewood pottery into a golden bowl of rose petals”.

Vince’s feud with a gang of kids, meanwhile, which culminates in one of the show’s funniest scenes involving a set of negotiations at a local burger joint, sees a 10-year-old Bobby George soundalike gruffly praising Vince’s hairline as part of their recent peace agreement: “Listen son, you’ve got the mane of Samson. You could be the lad in a Timotei ad. From behind, I thought you were Fabio!” Said child’s corresponding insistence that the gang should be taken to the ‘Kubrick retrospective at the NFT’ is the icing on a cake laden with rich dialogue and left-field surrealism.

15 Storeys High was near sitcom perfection, a half hour insight into Sean Lock’s exceptional comic mind which hummed with his signature style of idiosyncratic misanthropy and flair for the spoken word. As on stage, the comic’s ability to transform the mundane and the ordinary into the quirky and intimate seeped through the show’s DNA. 20 years ago, 15 Storeys cemented Lock’s status as one of the great comic voices of his generation. With his tragic passing, we can hope that we aren’t too late to truly acknowledge that legacy.

READ MORE: 15 Best British Comedies Of The 21st Century

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.