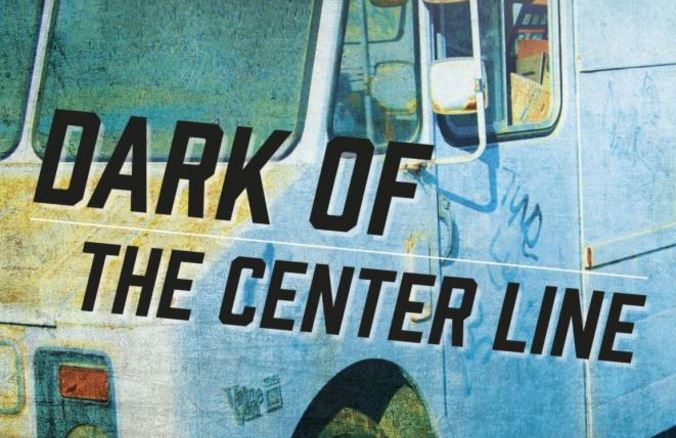

Recently we had the pleasure of chatting to Schuy Weishaar, author of the book Dark Center of the Line. We recently reviewed his book, and still had a few burning things we wanted to talk to him about. Luckily enough, Schuy decided to stop by. Thanks, Schuy, for sharing this wisdom.

Firstly, how are you doing?

I’m okay. No complaints.

Where did you get your inspiration for Dark of the Center Line?b

That’s a difficult question to answer because I threw a lot, personally, spiritually (if I can use that word without it sounding weird–I mean it in a rather traditional sort of way), and intellectually, into that book. I suppose, as far as the place goes, it was growing up where I did in Illinois that inspired me. It can be a lonely place, and it’s a mysterious sort of place. Allerton Park, for instance, is real place–and you could very well find a trail leading into the woods from one of the country roads out there in the middle of nowhere and find yourself approaching a giant centaur statue, as Abraham does in the book, or a naked Apollo or a garden filled with purple-glazed oriental Fu Dogs. And if you do a little research on the area (in and around Piatt County), you just keep finding things: places with almost mythic Native American stories attached to them; vigilante groups like the Calithumpians; and then the local lore about Satanists in cemeteries, haunted bridges, suicides and murders, that sort of stuff. Flannery O’Connor said something like any writer who is lucky enough to survive his own childhood should have a lifetime of material to write about. I think that’s right.

Writing can be an almost mystical sort of process because you pull from everywhere–all parts of life–things I did or thought about or heard stories about when I was seven or nine or thirteen or twenty-five or whatever. But then, in the present, right now, I’m pulling all of that into this moment, and I’m rearranging it, giving it to the experience or words of other people, and it gets to the point that that fictional person to whom I’ve given a lie that I told my parents when I was thirteen–a person who doesn’t exist properly–seems more real for the lie that I told my parents. It works better for him or it makes more sense for his life or story than it has ever for mine. So you give your life–the good and the bad–to this world, and it becomes more real to you than, say, the people you went to high school with. You live with this world. During the writing it’s almost like things happen while you’re not writing–like it’s a science experiment or something. You come back to it after a day or two, and stuff seems already to have happened, and you just have to figure out how to write it the best way you can. So it’s almost like the story short-circuits inspiration after a point.

What made you write a book with such strong references and allusions to religion?

Personally, religion has been important in my life for as far back as I have memories. This doesn’t mean that I’ve always been devout. Sometimes faith (or whatever you want to call it) being “important” has taken the form of wishing or striving to be rid of it or trying to think my way out of it. Almost like what Hawthorne wrote of Melville somewhere, that he could neither believe nor be comfortable in his unbelief. It’s mysterious, though, because inexplicably I kept finding myself more and more immersed. Consciously attempting disbelief essentially amounts to an act of faith, even if it’s inverted or somehow backward. It’s like this motif in some of the mystical Christian theologians of God almost being like this fathomless black hole of love that you will never understand that pulls you in in ways you don’t understand–they don’t say that exactly, of course, but that’s the sense. I’m very much attracted to the weirdness of faith, of religion, to its paradoxes, its mysteries.

For the book, though, specifically, I’m casting a wider net, so I don’t think it’s the kind of thing that can be minimized as the sort of book a “Catholic novelist” would come up with. There’s a lot of religion, but these allusions take a lot of different forms, ancient and modern, eastern and western, mystical and fideist, and most are grounded in pretty “earthy” circumstances at least to the degree that they rise into the “spiritual.” Like I said, I’m very much attracted to paradoxes and contradictions; I like fuzzy lines, but jagged ones are even better.

Which character(s) are you most fond of?

That’s not really a fair question, but I am very fond of Petunia.

Was there a reason behind having two chapter ‘7’s and ’13’s?

And you’re forgetting the 9’s (it’s less “sexy” in terms of associations, but they’re there if you go looking). In many ways the novel deals with doublings, recurrence, and repetition, but also with scission, with splitting and division. These numbers have a variety of associations in cultural and religious spheres, but also in numerology, and even in, say, the Major Arcana of the Tarot, and so on, and a lot of these lead from and back into one another in interesting ways. I’ll leave it at that.

Are there any particular messages in the book you would like readers to understand?

Yes. I will add only that I think the book is very funny.

Is there anything about writing that you find difficult?

Mostly just finding the time. I love writing myself into the middle of something and not really understanding how I got there or how I will get out. But to get there takes time. To do it well, especially at the beginning, I need long chunks of time. An hour or two is nothing.

What books/writers have influenced your work the most?

These books have been pretty important for me for some time now: Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground, Kafka’s The Trial, Kierkegaard’s Repetition, Camus’s The Stranger and his essays, Borges’s works, Melville’s stuff from Moby Dick forward, Beckett’s fiction, O’Connor’s Wiseblood, Harry Crews’ The Gospel Singer, Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio.

In crime writing, my favorites are Jean-Patrick Manchette, James M. Cain, James Sallis, Georges Simenon.

In the past several months, I’ve been impressed with some stuff by Hermann Hesse, Bruno Schulz, Julian Barnes, William Maxwell, Daniel Woodrell, and some Simon Critchley, Slavoj Zizek, Eugene Thacker, and also Rothko’s The Artist’s Reality on the nonfiction side.

That’s a scattered list anyway.

Do you have any weird or wonderful writing quirks?

I don’t think so. I’ve got plenty of personal quirks in real life. I feel most myself when I’m writing, so if there are quirks there, I don’t think of them as such.

Is writing more of a blessing or a curse?

Definitely a blessing–like a compulsory blessing

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.