No director has challenged the conventions of cinema quite as much as the legendary Stanley Kubrick. As a prominent figure of the New Hollywood era, Kubrick’s films are daring, dark and bizarre to the point that some were banned from screening. Unafraid to explore the seedy and the sinister, Kubrick’s movies often have an air of ambiguity, leaving audiences in both bewilderment and awe. His perfectioned cinematography is beautiful as well as iconic, being referenced and parodied for decades to come.

Who was he?

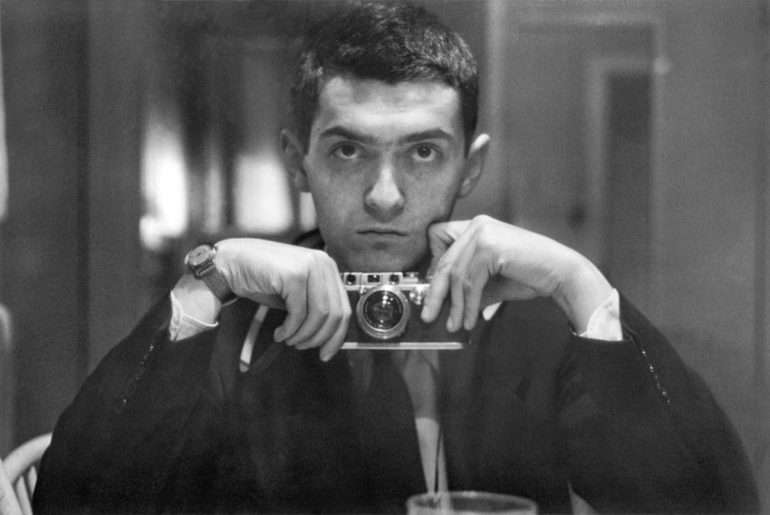

Stanley Kubrick was a New York-born photographer who later turned his hand to filmmaking during the 1950s. His creativity and skilled camerawork earned him Hollywood success, making a particular impression amongst critics.

Kubrick dedicated years of meticulous work to each of his projects, influencing future filmmakers such as Quentin Tarantino and Steven Spielberg with his experimental genius (though it did earn him the reputation of a reclusive workaholic).

Style and Autership

Kubrick’s films are often long and slow-paced with minimal dialogue. His experience as a photographer for Look magazine meant aesthetic precision was crucial to Kubrick’s visually astounding films, often cited as a visionary for his incredible imagination.

Kubrick had a scrupulous eye for detail; the epic scale of his films never making him fall short on complexity. His auteur status meant tracking shots, jarring zooms and perverse themes were frequent characteristics of Kubrick’s filmography. He also favoured the vague over the specific, leaving viewers with more questions than before the movie began.

Kubrick’s Best Movies

Dr. Strangelove (1964)

Dr. Strangelove Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb was one of Kubrick’s first major hits in Hollywood. Against his usual preference for drama and thrills, Dr. Strangelove is a comedy starring Peter Sellers (as three of the characters). Of course, it wouldn’t be a Kubrick films if there weren’t some dark themes involved. The nuclear threat of the Cold War is at the centre of Kubrick’s political satire, which is shot entirely in black-and-white.

Partially based on the 1958 novel Red Alert by Peter George, Dr. Strangelove mixes elements of fantasy with some truth about what really happened between the US and Soviet Union. Dr. Strangelove received controversial reviews – a common result of Kubrick’s films – for its story of an insane American General ordering nuclear attacks without permission from the President. But the accuracy of Dr. Strangelove isn’t really relevant – all that matters is that you get a good laugh out of it.

Full Metal Jacket (1987)

Vietnam films were a regular occurrence throughout the 70s and 80s. Americans were still recovering from the shock of an – arguably futile – war that was brought into the public’s living rooms for the first time, thanks to the media. Amongst The Deer Hunter (1978), Platoon (1986) and Apocalypse Now (1979), was Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket. The screenplay was based on Gustav Hasford’s 1979 novel The Short-Timers, and follows the story of Marine Corps recruits being brutally trained and plunged into war.

The iconic, foul-mouthed drill instructor and harrowing performances from Matthew Modine and Vincent D’Onofrio make Full Metal Jacket a masterpiece of anti-war cinema. Kubrick resists romanticised embellishments, instead giving a raw and accurate portrayal of how soldiers really experience the horrors of war.

Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

Tom Cruise is probably the last person you would expect to star in a morally questionable, outright bizarre Kubrick psychological thriller. Starring alongside his then-wife Nicole Kidman, Cruise plays a jealous doctor who finds himself involved in an erotic underground cult. One of Kubrick’s last projects (passing away six days after screening the final cut), Eyes Wide Shut is an adaptation of Arthur Schnitzler’s 1926 novella Dream Story.

When Cruise discovers the masked members of the promiscuous club, he realises he is in way over his head, and must decide whether or not to leave his marriage, or save it.

Eyes Wide Shut is considered more of an art-house film than Hollywood epic, with its slow pace, dreamy aesthetics and ambiguous subjects. Though some critics deem Eyes Wide Shut as an erotic thriller, many have argued the title to simplify and dismiss Kubrick’s exploration of marriage, sexuality and the human psyche.

The Shining (1980)

Based on the story by acclaimed horror novelist Stephen King from 1977, The Shining is an unconventional blend of the horror and psychological thriller genres. Kubrick delivers age-defining cinematography in The Shining, with the dialogue and architecture becoming a major reference point in pop culture. Though not a ‘scary’ movie per se, The Shining is definitely a disturbing cult classic that received mixed reviews upon release, but has since become a cultural monument of cinematic history.

Jack Nicholson plays the caretaker of an isolated hotel, trying to cure his writer’s block. His young son is plagued by visions, but it’s Nicholson who proves to be the true psychopath, terrorizing his family in a delusional frenzy.

What stands out the most about The Shining is its aesthetics; cinematographer John Alcott worked closely with Kubrick to achieve the film’s unsettling visuals, dominated by one-point perspective shots, tracking zooms and bold colour schemes. Kubrick’s dedication and precision to the art form is evident from behind-the-scenes stories of The Shining with him demanding 148 retakes of the same – pretty basic – dialogue scene.

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

A Clockwork Orange is probably the most controversial film ever made. So, it’s not surprising that Stanley Kubrick directed it. The dystopian crime movie, set sometime in the near future, is based on the black comedy by Anthony Burgess (1962).

The film depicts an unusual gang of delinquents, led by British teenager Alex DeLarge (Malcolm McDowell). This group of “droogs” terrorize their town with random acts of violence, explicitly raping a woman while singing the happy-go-lucky tune “Singin’ in the Rain”. Alex is then subject to brutal rehabilitation, which is equally as alarming as his crimes.

The most poignant, memorable aspect of Kubrick’s unique movie is, surprisingly, the audio. The soundtrack is mostly made up of classical music, juxtaposing the savage visuals, and the characters speak in the strange, not-quite English language of Nadsat. An alleged spur of copycat crimes meant A Clockwork Orange was banned in some areas, though is now hailed as a landmark film, demonstrative of Kubrick’s uncanny imagination.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

2001: A Space Odyssey was a game changer for the sci-fi genre – or even cinema as a whole. Based on Arthur C. Clarke’s short story The Sentinel (1948), 2001: A Space Odyssey explores complex themes of evolution, technology and existentialism.

When a group of astronauts are sent on a mysterious mission, the ship’s computer HAL begins to turn against the crew in an epic man vs machine combat, set against space. The inconclusiveness of 2001: A Space Odyssey only adds to the mind-bending experience of Kubrick’s ambitious filmmaking.

Not even the most modern, advanced CGI effects can match the extraordinary visuals of 2001: A Space Odyssey, winning the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects in 1968. Whether it’s a ten-minute cosmic sequence of dazzling colours or a still close-up of a single red light, Kubrick commands the screen like a master, igniting decades of debate over how to best interpret the film.

Keir Dullea leads the movie, which has since been recognised for its role in advancing film technology into what it is today. A truly exceptional work of art that every film buff needs to see.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.