If you’re a horror game junkie like me, you know what it’s like to be petrified after you’ve solved a certain puzzle and are waiting for the next inevitable monstrosity to be unleashed, or the uneasiness of walking around a seemingly deserted town with only the disjointed whisper of a haunting melody playing in the background. As unsettling as it is, we keep coming back for more (usually). But what is it about a well-designed horror game that makes it work? Well, there are many ingredients to this macabre formula, but arguably, one of the most important is the creative use of music and/or sound effects.

This commentary aims to delve a little into the effect music and sound effects have on us and what makes the music successful in achieving its desired outcome—scaring us shitless. (And you will notice a favorite reference game I use is Silent Hill, as it is one of the best incarnations of the horror genre.)

The elements described here for the most part refer to brooding psychological horror, though in some cases, can also apply to the oft-used “jump scare” based games. When this type of scare is used, usually one of two situations occur:

1. The player hears a noise or is made aware of some kind of danger. Then a reasonable explanation is found and the player rights the small problem. The player lets down his/her guard. And then the “real” scare executed.

2. The all-important audio quiets down or is all-together absent for a short time, which can either—again—cause the player to let down their guard and/or cause him/her to become leery and slightly cautious. Then, inevitably (for me anyway) the jump scare occurs.

A little (non-boring) background

“Not many things can claim to beat playing Silent Hill late at night, the atmosphere so thick you can almost feel it as a weight on your shoulders, and then your dog walks in, or a poster falls off the wall scaring you half to death. When something like that happens, you are playing a successful horror game.” (source)

So, in general, what are a few concepts that define a good horror game?

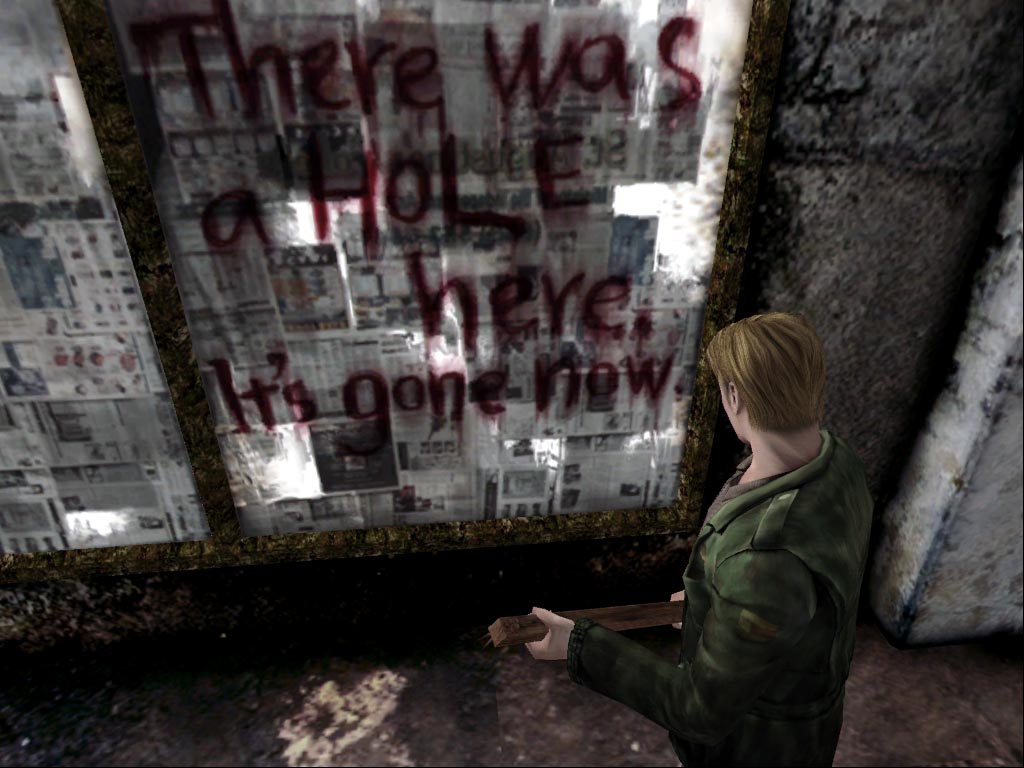

Well to begin with, it is imperative that the player be ‘present’ within the virtual space, to make sure he/she is as involved as possible. This can include not only sounds relating to where the player is in the environment, but also time of day, period in history, and architectural nature of the space. These various aspects can also be used ‘against’ the player, meaning to disorient them, confuse them, and make them uncertain of what is going on. For instance, when I was walking around lost in Silent Hill 2 with not one living human in sight, continuous bouts of rolling fog, and the town disturbingly quiet no matter my location, I was purely IN that gamespace; the seemingly humble little town was littered with small shops, gas stations, schools—along with stopped cars, trails of blood, and streets that suddenly ended and dropped off into an empty abyss.

The experience will cause the player to lose some of his or her self-consciousness due to the intense engrossment in the game; perceptions of time will become distorted.

A game can be coined as “scary”, but if I’m not immersed within the gameworld, I lose interest quickly.

Secondly, horror AND terror must be present. Horror is different than terror; horror is a frightful, revealing event; terror is the trepidation caused by it, which, thus, causes a fight/flight response. Thus, you could infer that the classic “jump scare” based horror—horror upon which the element of surprise is the tactic used to induce fear—is based primarily on terror. Think back to Resident Evil, during one of the most well-known jump scare scenes: walking down the 1st floor hallway, some Cerberus dogs burst through the dark windows — certainly terror-inducing!

Anxiety is a considerable component of a successful horror game, as anxiety is described as ‘fear from within’—where the object or situation causing the anxiety is indirect and distant; an idea expressed by Mark Grimshaw in his article “A Climate of Fear: Considerations for Designing a Virtual Acoustic Ecology of Fear.” (source)

This concept is very applicable to Silent Hill. If a “scary” event occurs, yet I have no inclination to run, fight or do much of anything, the scare isn’t successful. If I don’t feel a stirring of anxiety or uneasiness at any moment, the game isn’t doing its job.

Thirdly, uncertainty and mystery are crucial. According to the same article, “Uncertainty and danger are always closely allied; thus making any kind of an unknown world a world of peril and evil possibilities.”

Forewarning amplifies the startle effect; however, the absence of a forewarning (again, uncertainty) can create a more frightening overall experience.

This certainly applies to psychological horror, as often, there is much mystery and an ever-evolving story built upon the seemingly unknown. This can also be present in jump scare horror, as—for example— there is usually (as mentioned earlier) a short time when the always-important audio quiets down or is all-together absent before the inevitable “jump scare” occurs. In that “quiet” time, there is always uncertainty about what baddie is about to grab your ankles, jump through a window or break free from its cage.

In order to create the most frightening experience in the latter, it’s best to have the environment beforehand have no cues as to the nature of the threat, e.g., ways to ‘cope’ with it (e.g., size, strength, position). This occurs often in Silent Hill, for instance; all you have as an ‘alert’ to a near monster is radio static from a broken radio your character wears in many of the games. However there is no special music or any other allusion to the nature, size or strength of the enemy.

On to sound!

While it’s more common now to see games as a subject of study in academics, not much attention is given to how music and sound affects the gamers’ experience. Generally, certain musical cues and sound effects have the purpose of immersing the player in the narrative or having them solve some kind of problem within it.

To get more down and dirty as to the reason certain music or sound effects work, we need to look at a little theory. But it’ll be painless, promise.

First of all, to more easily illustrate the effect of music in horror-based games, for contrast, we can look at what are considered happier or “lighter” games. These types of games will often use a major scale.

Even more specifically, major triads (or major chords), especially those used at higher speeds, are utilized in games like Mario or Sonic the Hedgehog. When heard, it evokes more of a positive, happy response. See the following examples of a major scale and a clip from Mario here and here.

For horror, most often, the opposite is utilized, e.g., a minor scale. See the following example to contrast with the major scale above here.

Also, non-linear sounds are used to evoke the uncomfortable feeling of something not being “right” in the area or environment. Non-linear sounds exceed the range of the instrument or suddenly change frequency, such as the staccato violin stabs in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho.

They also are present in nature, in an animal’s distress call — the reason why we fear them when we hear them. Our brain has a natural aversion to these types of noises. This is why they work so well in horror games, and horror movies.

These types of sounds are present in both psychological horror as well as jump-scare horror, example here.

Examples of this non-linear quality are illustrated below, in 3 notable horror games: Silent Hill 2, the original Resident Evil, and Amnesia: The Dark Descent. Note that this trait is sometimes not used throughout the entire length of the song or songs.

Using my personal favorite game —Silent Hill— to examine horror game music and sound in more depth, let’s go back to minor key tonality.

Although the classic Silent Hill soundtrack is quite varied, it contains no music in a major key; “Therefore, musical scores like Akira Yamaoka’s for Silent Hill never have the safe moments of exploration allowed by platform games, and they must sustain a consistent and pervasive mood of terror or apprehension in the player” (source: Game Studies: Play Along – An Approach to Videogame Music by Zach Whalen), which it manages to do brilliantly. I personally have never truly felt safe in any part of the game. There is not a proclaimed ‘safe zone.’ There was no area where I was sure nothing even mildly horrific would happen.

Another important concept to take note of is that there is rarely a ‘tonal center’ in Silent Hill’s music; e.g., a ‘backbone’ or ‘key’ to lean on, so to speak — much like the actual situation in the game is without its ‘tonal center’ (in a metaphorical sense); this is known as atonality.

As Zach Whalen accurately illustrates: “…the space of Silent Hill undergoes rapid and grotesque physical changes from a foggy, empty town that is otherwise normal to a blood-soaked, nightmarish parody of the same space. This change is always reflected musically as the quietly unnerving throb of the foggy Silent Hill gives way to a cacophonous ringing of metallic noises and atonal chaos.”

To demonstrate, we’ll take the well-known alley scene from the introduction of the original Silent Hill; notice the percussive atonality as Harry enters the alley. Later in the scene, we start hearing some eerie, sustained organ chords, providing some sense of tonality; however, the chords never resolve. Other sounds are also introduced, in a layered fashion.

This specific musical formula in the alley sequence is present throughout Silent Hill to elevate the fear response; e.g., a new element of sound is layered as a scene progresses.

A good example of atonal chaos and non-linear sounds or music in a jump scare-based game can be found in the classic Resident Evil 1 scene, where an uneasy silence is broken by a frenzied, atonal barrage of violins as dogs jump through ground floor hallway windows (as mentioned earlier).

Battle sequences are handled a bit differently in horror as well, especially Silent Hill:

“For example, the battle scenes. There’s a certain genre of “combat scene” music, but instead of using combat music I think about what the character is thinking about and what made him get into a fight. So I don’t really use combat music just because it’s a combat scene.

“…It’s not like orchestrated or anything. I try to make it dramatic, a different type of music.

“… I try not to make a pattern that the user will get used to. I want to make variations that users cannot anticipate.” (source: Interview: Silent Hill Sound Designer Akira Yamaoka)

The first battle with the infamous Pyramid Head, in the Otherworld incarnation of the gameworld, within the Blue Creek Apartments, is a great example — the music consists of an eerie atonal hum and somewhat randomly placed industrial noises that do take on some semblance of a progressive, broken rhythm.

As I’m sure you can gather, especially in horror, sound is of utter importance to the horrific impact of the game as a whole.

In fact, in a 2012 University of Abertay study, where 12 students were hooked up to heart and respiration monitors, they were asked to play a section of Amnesia: The Dark Descent with the sound off, then on. “It’s worth noting from a psychological standpoint that while playing the game heart and respiration rates increased by 20bpm and 13bpm respectively when audio was switched on.” (Source)

The addition of sound and its excitable affect on heart rate and respiration is deemed even more extraordinary since in the part participants played, nothing that would be deemed classically ‘exciting’ was happening—no fighting, no enemies; only exploration.

It is truly remarkable what incredible significance well composed and designed sound and music can have on the gaming experience, especially in horror-based games.

Before I go, I’ll leave you with this thought:

[Fahs, 2008] (source)It isn’t what you see, but what you can’t see. It’s the suggestion; the subtle teasing of the subconscious; the lonely creaking of the floorboard resonating throughout an empty hallway; the slow advance around the corner; the swelling sense of dread as the ever-present evil looms near refuses to reveal itself. Fear is not an adrenaline rush. It’s that helpless feeling of be alone in the dark.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.