America has always boasted a proud tradition of animated programming, a tradition that has never translated across the Atlantic. If Walt Disney was to blaze the trail for drawn technicolour features in the world of film, Warner Bros. Cartoons (later to become Warner Bros. Animation) set the platform for this noticeably American phenomenon to transfer to television, iconic shows such as Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies bringing staples such as Daffy Duck, Bugs Bunny, and Tweety Pie to mainstream American audiences in the 1930s.

Latterly, production company Hanna-Barbera came to dominate American animation between the 1950s and the 1980s, setting the tone and feel for the country’s animated shows, from Yogi Bear and Top Cat to the Jetsons, Wacky Races, and Scooby-Doo. Almost single-handedly, Messrs Hanna and Barbera transformed the traditional American televisual and cinematic landscape into one which had animation firmly at its core.

At the heart of this was The Flintstones, a ratings smash first broadcast on ABC in 1960, the first animated show to hold a prime-time slot on American airwaves, pushing the niche medium further into the centre of US culture. Little by little, cartoons were being seen not just as diversions for children but for entire families. While the concept of ‘adult animation’ wouldn’t truly exist until the 80s and 90s, the groundwork was being laid by placing non-live-action productions alongside traditional, mainstream programming.

As cartoons would eventually diverge, with some eventually catering exclusively to adult audiences, an established tradition of home-grown children’s cartoons facilitated this split. Entire programming schedules, such as the ‘Saturday Morning Cartoon’ slot from the 1960s to the 1980s, ensured that animation remained firmly in the public psyche. From there, shows on emerging cable channels such as Nickelodeon, Disney Channel and Cartoon Network ensured that cartoons became instilled in the minds of American kids, teens and their parents, wIth Cartoon Network becoming the first 24-hour all-animation channel in history.

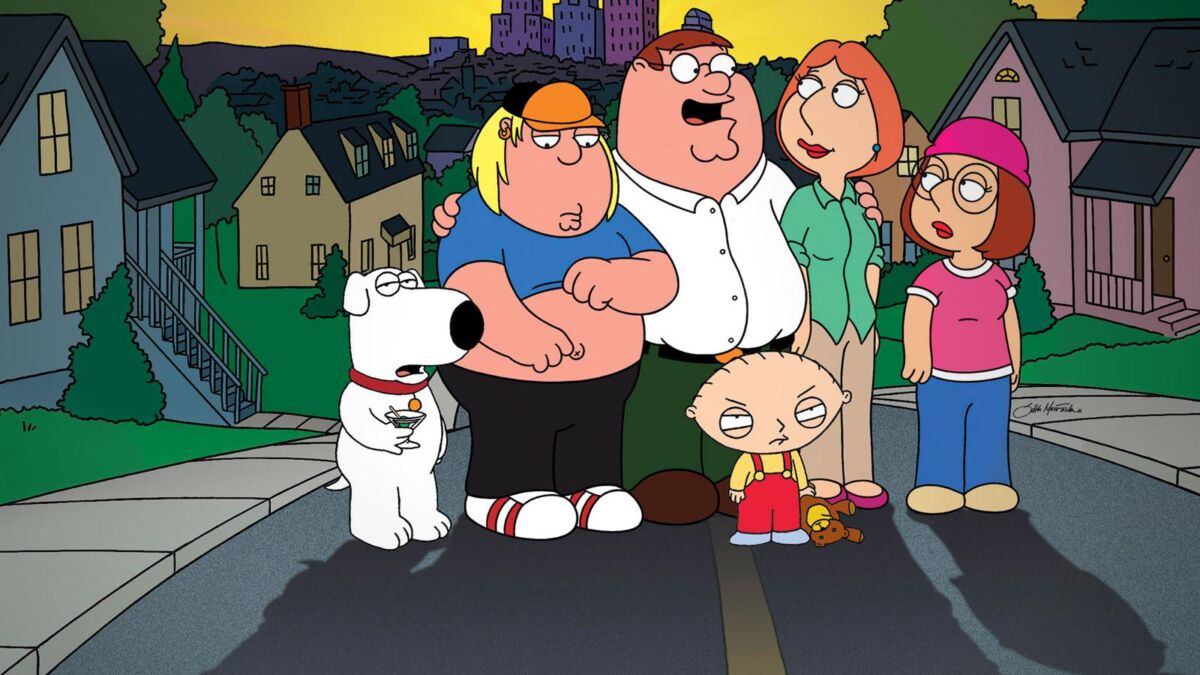

Not only did the presence of children’s TV keep Americans watching cartoons, it also kept writers writing them, smoothing the transition from working on kid’s shows to more adult content. Dexter’s Laboratory creator Gendy Tartakovsky would later go on to birth cross-generational hit Samurai Jack (and, more recently, Primal) for Adult Swim, Cartoon Network’s designated programming block for more mature shows like Aqua Teen Hunger Force and Rick and Morty. Seth McFarlane, meanwhile, worked on the likes of Dexter’s Lab and Johnny Bravo before moving into alternative comedy with Family Guy in 1999.

Such transitions aren’t possible for UK writers. Working on children’s TV shows before moving to more adult output certainly isn’t uncommon for British creatives, but given that the UK has few home-grown kids cartoons for which to write, the process never translates to working on adult cartoons. Most great British kids’ shows use different formats to the drawn line, from puppetry (Rosie and Jim, Sooty and Sweep), to anthropomorphic (Teletubbies) and live-action (Horrible Histories), or indeed imported kids’ shows like Mona the Vampire or The Cramp Twins. A home-grown cartoon culture simply doesn’t exist in British television.

Because of the growth in this hand-drawn tradition, and cross-pollination from those shows aimed at kids to those targeting adults, America has nurtured a culture in which animation-focused creatives can flourish and to which audiences are accustomed and receptive. The Flintstones not only proved that animated shows could command mainstream ratings, it also gave producers confidence that cartoons could work as profitable enterprises. The ’70s and ’80s saw mainstream adult-oriented animations from the likes of pioneer Ralph Bakshi gain a degree of popularity, including X-rated features Fritz the Cat and Spice City, followed by the rise of imported Japanese anime and animated music videos.

The Simpsons, the show which would ultimately eclipse The Flintstones as animation’s most popular and enduring cartoon family, took the mantle from the residents of Bedrock and created a phenomenon which would ultimately spur its own cartoon Renaissance, at the heart of which was more mature content which Groening and co. helped pioneer.

Since then, imitators, tributes and homages have all taken some degree of influence from Springfield’s iconic inhabitants. South Park expanded on the show’s subversive, satirical streak and transposed it to a superficially simplistic artistic style, while King of the Hill, Family Guy, Bob’s Burgers, and F is for Family all drew inspiration from the dysfunction of the traditional American family. The floodgates now open, the late ’90s and early 2000s saw Cartoon Network introduce its Adult Swim programming block, its first forays into cartoons aimed at adults coming in the form of parodic talk show parody Space Ghost Coast to Coast.

Adult Swim would go on to inject massive momentum into the push for American adult animations, producing subversive classics ranging from Harvey Birdman to Robot Chicken, Sealab 2021 to The Venture Bros., The Boondocks to Final Space, while syndicating and importing other popular shows like Family Guy and Cowboy Bebop, ensuring the latter imports found a receptive audience. This confidence to even attempt such a feat was likely influenced by the presence of an existent programming platform, the successful import of adult-oriented Japanese anime to America, and The Simpsons’ colossal popularity.

No such titan reigns over the British Isles, no great success story existing to inspire confidence in others or create a national zeitgeist. While a few meagre offerings have tentatively touted themselves as ‘Britain’s answer to’ the likes of South Park or Family Guy, none have done so with conviction. If anything, adult British cartoons have only served to reinforce the idea that such shows cannot thrive here. Despite a few flashes of brilliance from the likes of surreal dystopian nightmare Monkey Dust and the foul-mouthed satire of Modern Toss, most offerings have been uniformly awful.

British cartoons would do more damage to the overseas perception of Britain than colonialism or Piers Morgan – if, of course, anyone had ever seen any. The woeful school-based antics of Bromwell High sank without trace, mainly due to the fact that the only thing worse than the Microsoft-Paint level of animation was the show’s scripts. The baffling Popetown, touted as “South Park meets Father Ted”, was never fully screened on terrestrial television, which in retrospect has been the show’s only saving grace.

Meanwhile, Full English – cited as Britain’s answer to Family Guy – was the sort of programme that made you question how a country that produced Stephenson’s Rocket and Peep Show could also be responsible for such shallow, half-baked garbage. Show any of the above to a room full of Americans and they’d likely be sending care packages to Britain for fear that it was a barren cultural wasteland stuck in the year 1989 and trying to produce TV shows with an old Atari hooked up to the Compuserve network. Such shows, influenced by finer American properties and hampered by confused transatlantic stylistic visions, have only served to hammer further nails into dreams of a British answer to Archer or BoJack Horseman.

Perhaps these shows’ inherent inability to gain traction with a British audience stems from the fact that the American sense of humour, so prevalent in their animated series, doesn’t transfer so easily to Britain. While there is no inherent reason why British creations should be live-action, because of a necessity to ape their American counterparts, a clash of styles often occurs in which quickfire, zany and slightly self-aware humour collides with the English sensibilities regarding quiet misanthropy, repression, suburban claustrophobia and existential disillusionment. Without any great works such as The Flintstones or The Simpsons from which to draw inspiration, British animated sitcoms are usually Frankenstein affairs that flounder as a result. There is, in short, no animated equivalent to Fawlty Towers. A culture of British cartoons has simply never existed in the way that it has in the States.

Certainly, British comedy tradition has bypassed those hand-drawn formats in favour of its own signature setups. Single-camera sitcoms that dominated the landscape during the 70s and 80s, such as Some Mothers Do ‘Ave ‘Em or Are You Being Served?, relied far more on given location setups, their tone, pace, and feel designed to appeal to live audiences. Even something as simple as the presence (or absence) of a laugh track is massively influential in setting a show’s rhythm and comic style.

None of this has been helped by British comedy’s willingness to explore other avenues aside from animation, avenues that are often dictated by budgetary constraints and practicality. Traditional single-cam sitcoms might have broadly given way to sketch shows and later alternative subversive satires like Brass Eye, Nathan Barley, or Garth Marenghi, but the rise of what the BBC classifies as ‘Low-Cost Entertainment’, i.e. TV panel games, chat shows, and other ‘real-life’ formats have dominated much of the British mainstream output.

If British commissioning editors are to sink money into a less budget-friendly format, the chances of placing such a risk on a cartoon are decidedly slim considering that they often cost a lot and require more time and people-power. Family Guy, for instance, reportedly has production costs of a cool $2 million dollars per episode, although much of that is spent on paying its voice actors’ colossal wages.

Could animated shows ever find a UK audience? Current evidence is gloomy, but it seems there isn’t anything inherent to the British sensibility that would preclude the use of the animation, especially given the popularity of American shows broadcast in the UK on networks such as BBC3, ITV2, and E4. Considering the range of tones, styles and voices in American animated sitcoms, from the parodic space adventures of Futurama, the quirky surrealism of Bob’s Burgers or the subversive anarchy of Beavis and Butthead, surely there’s enough talent to make the format work with a distinctively British spin? Yet with the rise of the internet, globalisation and transatlantic streaming, another question occurs: do we even need to? Given America’s continued enjoyment of a new Golden Age of animation, attempts from Blighty – from Warren United to Headcases – might be received as they always have been: little more than pale imitations.

READ MORE: 6 90s Cartoons That Were Ahead of Their Time

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.