Trainspotting, the sophomore 1996 feature from British director Danny Boyle, was a hand grenade of pure cinema.

It was a calling card for bold new talent, in front of as well as behind the camera. It boasted a boutique-mixtape soundtrack whose selections still dominate indie club nights even now. It was a zeitgeist whirlwind which changed the British film industry and would go on to become one of the most important films of the 90s. It was also one of the most empty movies ever made.

Twenty years later, Boyle has decided to put the band back together and make a sequel. If ever there was an example of tempting creative fate, this is surely it. And yet, somehow, the end product is a movie that transcends its predecessor in nearly every way imaginable. It may not have the same explosive impact or visceral punch as the original, but it makes up for the shortfall with an emotional wallop that few could have seen coming.

What was Trainspotting ‘96 about? Nihilism, friendship and addiction. That was pretty much it. What is T2 about? Christ, where to begin? Memory, fate, the struggle for closure, identity, the ruthless passage of time, gentrification, moving on, regret, nostalgia (and the folly thereof), the power of storytelling and, of course, friendship and addiction.

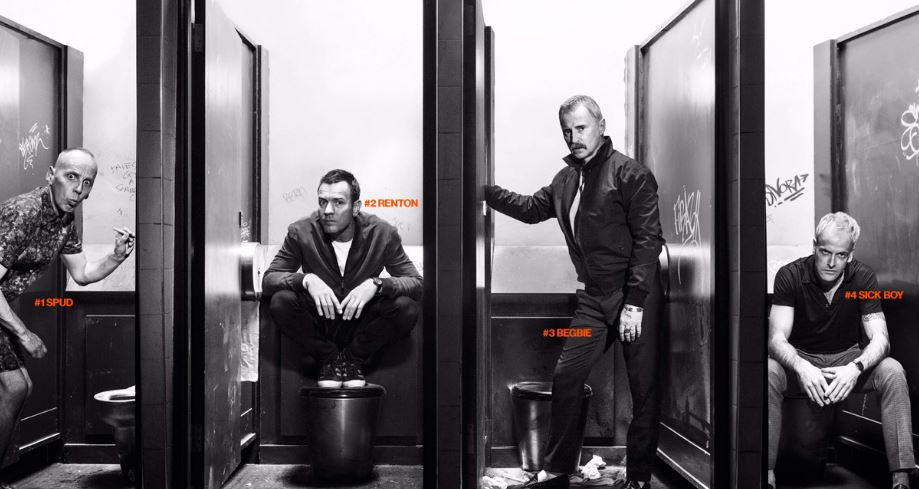

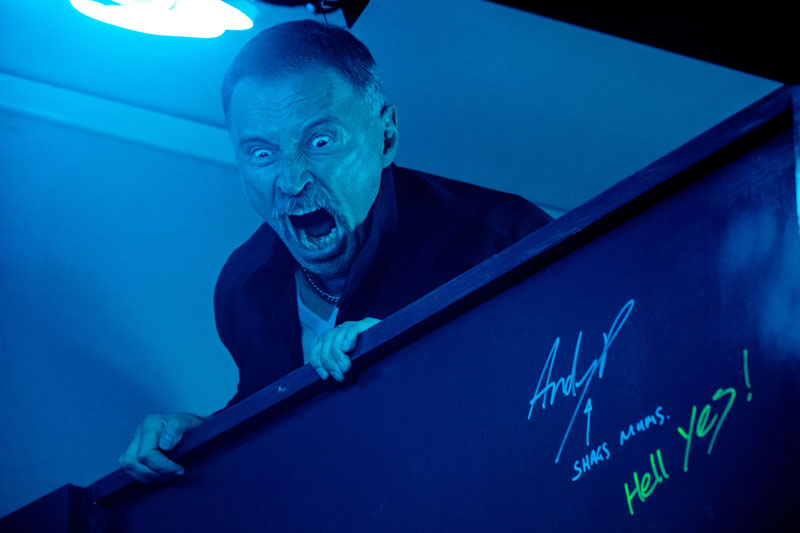

We join our antiheroes exactly 20 years after Ewan McGregor’s Renton, clutching a bag full of stolen cash, skipped merrily over London Bridge to the sound of Underworld. Returning to his native Edinburgh, he finds a city losing its soul and is reunited, one by one, with his former comrades-in-arms; sad, kindly Spud (Ewan Bremner), misanthropic Simon (Jonny Lee Miller) and the psychotic Begbie (the magnificent Robert Carlisle, delivering the performance of a lifetime). Unfinished business looms over all of them. A happy ending seems unlikely.

Wisely, Danny Boyle and his collaborators have decided not to make the same movie twice. A few visual cues harken back to the original, and audio motifs have been either reworked or pared down for effect. Boyle is at the absolute height of his powers here and the film is fizzy with visual invention and dynamism. He is a master conjuror of celluloid, able to get so much out of so little. T2 reminds us, yet again, why he is the UK’s greatest living director.

When Trainspotting was released in 1996, there was nothing else like it, but in places it felt like an extended music video. The second film has depth in spades, going to places far more interesting and uncomfortable than the first one; how do we make sense of our lives while watching the years pass us by? Can you ever really escape yourself? Why are we so obsessed with the past? What good are we doing by clinging onto it so tightly? Post-movie conversations in the pub were made for films like this.

It only stumbles slightly. Were it not for a clunky attempt to recreate the iconic ‘Choose Life’ speech midway through the film, I’d be giving it 10 out of 10. Elsewhere, Kelly Macdonald, such a vital part of the original, is criminally under-used. Maybe all this is in keeping with the film’s subtext; nothing is ever quite the same second time around, however much you want it to be.

T2 is a rich, empathic tapestry of a film that reminds us of cinema’s ability to push our buttons. It makes the viewer think about life from other people’s perspectives while examining their own. Some parts of the movie are repulsive, some are hilarious, some are brutal and some are tender, but in the end it all comes together beautifully.

Most importantly, T2 is a great night out at the cinema. Who would have thought revisiting a classic 20 years hence would reap such great rewards?

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.