Don’t call it a comeback. Seriously, don’t, as far as the Sega Dreamcast is concerned. What many hoped would be a grand return to form for Sega turned out to be the final nail in the coffin of making their own hardware. It’s a sad story, once again filled with odd choices on the Japanese giant’s part, but this time, their undoing mostly came down to the fact that there was just no room left for anyone but Microsoft, Sony, and Nintendo.

But is that what really happened to the Sega Dreamcast, despite over 500 games being produced for the system between 1998 and 2001, and a decidedly splashy PR blitz that wasn’t wholly successful, but sure was fun to watch?

Sega lost a significant chunk of time mucking around with the 32X and Sega CD in the 90s, coupled with the disastrous Sega Saturn run, and in that period Sony became the console king. Microsoft was coming down the track with their console, and despite a rocky go for the Nintendo 64, Nintendo was still very much in the fight. Where does that leave a company that hadn’t released a successful console in almost seven years?

Sega saw the writing on the wall by the year 2000, with good-but-not-breathtaking sales for the Dreamcast topping out at a little over nine million. It didn’t take Sega very long to decide the Dreamcast was a mistake, as well, and as we look at how the Sega Dreamcast failed, we’ll see a story that in many ways, was very familiar to a company that gave Nintendo a serious challenge in the early 90s. At the same time, the story of the Sega Dreamcast is a wholly unique chapter in the extraordinary history of Sega.

They soon made the choice to abandon the system even earlier into its lifespan than they had with the Saturn just a couple of years prior. Some reports suggest the Dreamcast was doomed shortly after it was announced, with Sega never quite recovering from the waking nightmare that was the release of the Saturn and wanting to get out of the hardware business for good.

That would track with a company that began planning the Dreamcast very early into the life of their heavily-hyped Sega Saturn. The new system would come to be known by a variety of project names, including White Belt, Black Belt, Guppy, and Dural, depending upon which hardware team we’re talking about.

But there’s a lot more to consider with this story, beyond Sega’s then-shocking plans to start anew after so much had been spent on the Saturn. You can begin with Sega of America President and CEO Tom Kalinske leaving early into the Saturn’s release, replaced by recent Sony hire Bernard Stolar. It would be Stolar’s decision to give up on the Saturn and seek redemption with the Dreamcast, later saying “I thought the Saturn was a mistake as far as hardware was concerned. The games were obviously terrific, but the hardware just wasn’t there.”

A Short Life on Saturn

Let’s go back just twelve months or so from the release of the Sega Dreamcast in Japan on November 27th, 1998, in the US and Canada on September 9th, 1999 (9/9/9), and in Europe on the less-cool-sounding 14th of October of that year. The year is 1997, and the Sega Saturn is getting pummeled by corporate arrogance, the rising tide of enthusiasm for Sony’s PlayStation, and Nintendo providing considerably more stability than their heated rival of nearly a full decade.

Former Sega of America CEO and President Tom Kalinske is long gone. In his place, it’s Bernard Stolar indicating in a 1997 interview that “The Saturn is not our future.” The quote has been famously, and perhaps mistakenly, attributed to remarks Stolar made at E3 1997. Regardless of that, and despite plans to continue supporting the Saturn for at least a little while longer, this was a bold statement just two years into the release of Sega’s solid-but-beleaguered console. “The company was bleeding cash,” he would later say, “And I wanted to build a new team.”

The decision on Stolar’s part was controversial then and is still remembered with some scorn by Saturn’s fans. Stolar had already frustrated them with his dismissal of localizing certain games for the western market, further infuriating them with his inability to see the growing potential of RPGs with players in North America and Europe. His decision to ultimately kill the Saturn after two financially miserable years for the system was an unpopular one, to put it mildly. A trickle of releases would continue through 1997, and even into 1998, but the writing was on the wall. Sega was ready to start a new chapter.

Surely, they had learned all their lessons, and it would be smooth sailing from here on out.

Yep.

Dreaming Big

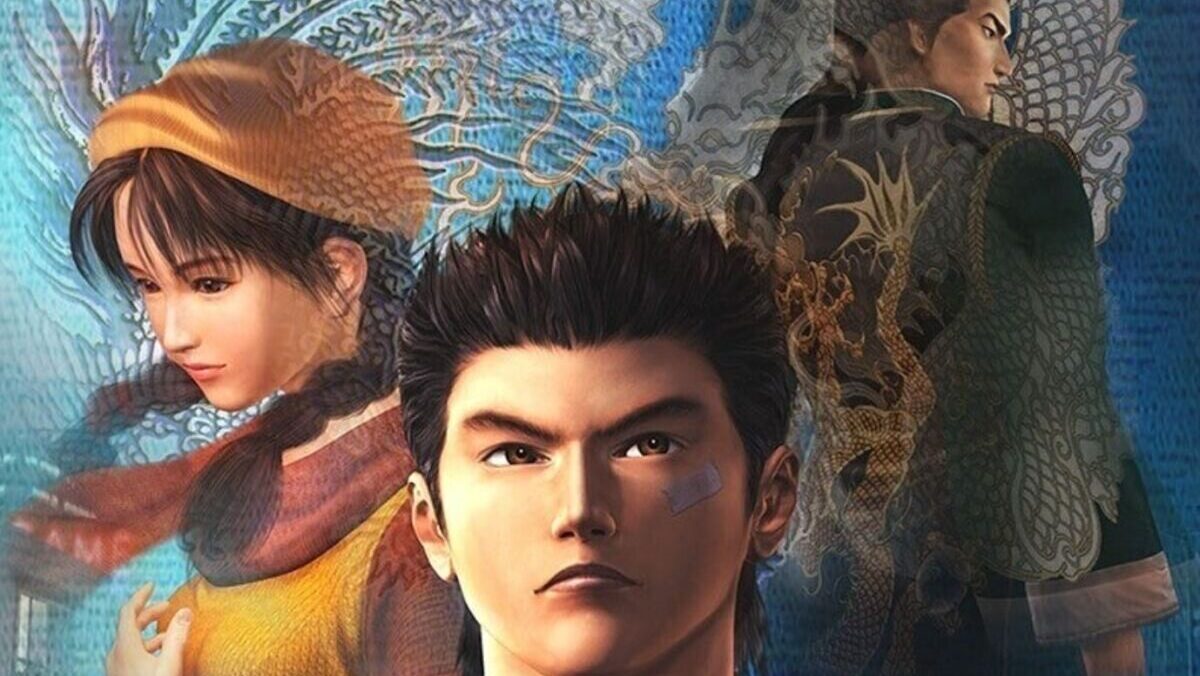

It’s interesting to remember now that the enduringly popular Shenmue series initially began as a major effort to drag the Sega Saturn out of the doldrums. The decision to move on from the Saturn far sooner than perhaps anyone had originally planned, shifted the game to becoming a hopeful “Killer app” for a system that was announced shortly after Sega’s grim reporting of losses in excess of ¥35.6 billion, or $269.8 million in US dollars. Before the last Saturn games were even out the door, rumors spread by Sega themselves indicated that the new console was being fast-tracked.

And this time, things were going to be different.

And to some extent, things were different. It would be simply wrong to say Sega didn’t learn a single thing from the Saturn’s failure. The company made some smart moves early on, bolstered by an enthusiastic approach by Stolar and other top executives at Sega. Two development teams had worked on potential hardware for the Dreamcast itself, one from America and one in Japan led by Hideki Sato. While both teams developed similar hardware, a serious misfire on the part of 3dfx, the company chosen by the American team, would lead to lawsuits and bad blood. 3dfx had revealed too much information on their recent work with Sega, leading to the Japanese team’s concept for the Dreamcast being chosen as the one that would go forward.

Stolar would later deny Sega chose one over the other due to poor judgement by 3dfx. “It was really just the technology end of it,” he claimed.

With the system in full production mode, things seemed promising, and the gamble to begin fresh had at least a shot at working out, despite the time Sega spent on this new system being dominated by Sony and Nintendo, leaving a thriving, healthy Sega console further and further in the foggy past. Yuji Naka and his legendary Sonic Team were working on a powerhouse 3D Sonic title. Shenmue was shaping up to be something special. Capcom, Midway, and even Namco, fresh off the success of games that helped put the PlayStation over the top, were preparing arcade-style heavyweights to debut on the Dreamcast.

Sega would even hedge their bets with a full line of incredible sports games that could only be played on the Dreamcast. They even went so far as to purchase Visual Concepts, a San Rafael, California company that would make sports titles such as NFL 2000 and NBA 2000 available when the system launched in the United States. This seemingly smart decision, however, would later come back to haunt Sega. We’ll get into that soon.

On the precipice of its launch, the Dreamcast looked strong. It would use the Hitachi SH-4 architecture, with an eye towards making programming games for the system considerably simpler than it had been with the Saturn. Again, Sega wanted to do things right this time, and this focus ensured the distinct possibility of a far more successful launch. The Dreamcast would feature a 100MHz Clock, 7 million textured and lit polygons/s, 100 Mpixels/s, 8MB of memory, full screen anti-aliasing, volumetric effects, Alpha Blending, and more. In short, it was a system that could handle what Sega had in mind for not only themselves but the various third-party developers that were ready to make games.

Sega was even reimagining the relationship the console would have to Sega’s arcade business with the release of NAOMI in 1998. A mass-produced, cost-effective machine that would utilize large ROM cartridges for its games, Sega was confident in not only developing a new generation of extraordinary arcade titles, but that these games could then be ported to the Dreamcast with ease.

Sega and Bernard Stolar were also banking on people getting excited about the Dreamcast having a modem, making it the first console to offer this. Sega was right to see a lot of potential in the future of online gaming.

The stage was set. The Dreamcast would launch in Japan on November 27th, 1998, with a release the following year in the US and Europe. Sega felt confident for the first time in what at least felt like a long time. Fans were excited, as well. What could everyone expect?

“A mixed bag” would be putting it mildly, but initially the forecast was far less gloomy than it had been for the Saturn.

An Underwhelming Japanese Launch

The Dreamcast started strong in Japan. Pre-orders came in at a steady pace at the outset, only to be met with disaster when Sega found themselves contending with a massive shortage of the PowerVR chipset that would be used to power their system. By Sega’s own admission, they believe they could have sold 200,000-300,000 more units if the supply had not been shortchanged by a startlingly high failure rate of the chipsets during the manufacturing process.

Sega would sell out on launch day in Japan, but the company failed to meet its shipping objective. Further dampening the launch was the reality that only one of the four launch games, Virtua Fighter 3, sold particularly well. Both Sonic Adventure and Sega Rally Championship would be on the way in short order, but not on release day as had been previously promised. To some it felt a little like “more of the same” with Sega. There were even reports of disappointed consumers returning their Dreamcast to get PlayStation stuff. Sega had hoped to establish a dominant lead before Sony and Nintendo came out with their new consoles, but this was becoming increasingly less likely.

The Japanese launch could best be described as “tepid,” but arguably better than the Saturn. By the time the North American launch was being prepped, Sega was selling the Dreamcast at almost a complete loss, announcing a new online network for their modem, and replacing Bernard Stolar in the United States with a fresh face named Peter Moore.

At this point, it was becoming increasingly obvious that Sega would need to win and win big with the American market, as well as other markets like Europe, if they had any hope of surviving the dawn of the new millennium.

What Do You Mean “It’s Thinking”?

For many, the Dreamcast US advertising blitz throughout 1999 is fondly remembered today for being interesting and ambitious, with the tagline “It’s thinking.” This reference to the untapped power of the Dreamcast suggested something unique and mysterious. Perhaps too mysterious, as some have since argued that the campaign was far too vague, with claims that the campaign was mocked from the start.

Regardless of whether or not that’s true, Sega did get people’s attention. Sporting its unique controller, a Visual Memory Unit (VMU) memory card with its own screen, and more than 17 launch games, far more than the Japanese launch, the Sega Dreamcast opened big on September 9th, 1999. With more than $97,000,000 in sales, it was the most successful console launch in history up to that point. Sega for the moment appeared to be back, with several games receiving hefty praise and strong sales, including Sonic Adventure, SoulCaliber, and NFL 2K.

Unfortunately, the only company that suffered during the Dreamcast launch was Nintendo, with reports that far more N64 owners were trading in their systems for a Dreamcast than PlayStation owners were. Sony was at the top of the heap at this point, and Sega couldn’t put much of a dent in their fortunes. Sega’s online service was announced the day Sony put out the word on the US release of the PlayStation 2, but SegaNet suffered due to the inability of broadband internet to expand into more homes as Sega had hoped it would. By the end of 1997, Sony had sold over 20 million consoles. Nintendo was barely keeping up, and they were far more consistent with their console success and game releases than Sega had been in a long time.

Sony Finishes The Job

The PlayStation 2 just couldn’t be stopped. Even Nintendo would find that out the hard way. “Dreamcast was a phenomenal 18 months of pain, heartache, euphoria,” Peter Moore would later say, after inheriting the thankless job of running Sega’s American branch from Bernard Stolar. “We thought we had it, but then PlayStation came out, that infamous issue of Newsweek with the Emotion Engine on the cover…and of course, EA didn’t publish which left a big hole, not only in sports but in other genres.”

What Moore is referring to of course was the infamous falling out between EA and Sega, once best buds in the early days of the Genesis. EA didn’t want to share sports game space with Virtual Concepts, the company Sega had purchased to make exclusive sports titles, who are now under the 2K Sports umbrella. While Sega would put out some brilliant sports titles during the Dreamcast’s life, franchises like Madden just had too much inherent name value to be defeated.

And that is perhaps the most consistent thread in the regrettable history of the Dreamcast: Anything the system could do, someone else, usually Sony, could do better.

Sega had a wide window in which to establish a lead over the PS2, but the PS2 eventually launched in most major markets in the early months of the year 2000, and Sega’s lead, defined by sales goals Sega failed to meet with the Dreamcast and its hardware, disappeared completely. The PlayStation 2 had more anticipated games, backwards compatibility with the massive PS1 library, and perhaps most importantly in the year 2000, a functional DVD player.

Sega, meanwhile, could do little more than bleed money. Slashing console prices helped them stay in the game, but at what cost? “We were selling 50,000 units a day, then 60,000, then 100,000,” Peter Moore said, “But it was just not going to be enough to get the critical mass to take on the launch of PS2.”

Sega losing most of the people who truly believed in the Dreamcast didn’t help matters either. In particular, one of the Dreamcast’s biggest proponents, Hayao Nakayama, left his position as CEO of Sega. Longtime Sega executive Shoichiro Irimajiri was gone by this point, as well. Internal restructuring by people who wanted to simplify things at Sega on a profound level soon became a growing call to leave the hardware business behind.

Eventually, despite taking a moment to throw some shade at Sony over their PS2 shipment difficulties, the call was answered. On January 31st, 2001, Sega announced that they were abandoning the Dreamcast worldwide and leaving the hardware business for good. They would remain open to begin developing third-party software for other consoles, and this has been the company’s focus ever since.

Remembering the Dream

It’s easy to call the Dreamcast another Sega failure, but clearly this was a wonderful, sometimes bizarre console that had virtually no chance of recouping its costs, let alone dominating a market that was now virtually unrecognizable to Sega from when they had broken into the field years earlier. From its controller and VMU memory card, to groundbreaking titles like Jet Set Radio, Crazy Taxi, and Shenmue, and also the utterly bonkers and incredible Seaman, the Dreamcast is one of the better pieces of pop culture from its time and place.

Sega is still around, and that does count for something with a company that’s home to so many iconic characters and legendary games. The list of good Dreamcast games is far longer than many give it credit for. Perhaps there’s a hint of nostalgia behind remembering the year 1999 and the promise of what the future might hold, represented to some degree by concepts like the Dreamcast, and where we as a culture went from there.

Perhaps. But when you cut through the static of Sega’s poor business decisions, bad luck, stiff competition, and our own memories of younger, perhaps better days, what you’re left with where it concerns the Dreamcast is a fascinating system with dozens of games you could pick up today and enjoy. True classics never truly age where it counts, and the Dreamcast had a bunch of them.

“In the end,” Peter Moore once said, “It didn’t work out. It was tough, but those were great days and I’ve never met anybody who regretted buying a Dreamcast. Soulcalibur anyone?”

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.