Detractors often pigeonhole French cinema as snooty and overly artsy. Enthusiasts spend a lot of time combing through the New Wave classics again and again. But if your interest in movies is matched with an interest in the French language, there’s a lot more than just artsy New Wave to explore.

From Belgium to Canada, and Poland to West Africa, plus a few from the Francophone motherland herself, here are ten French language flicks you can rely on for an enjoyable time.

Plein Soleil (Purple Noon)

(Directed by René Clément, French production shot in Italy, 1960.)

Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Talented Mr. Ripley found new fame in 1999 with Anthony Minghella’s screen adaptation starring Matt Damon. But decades before that, the cool eyed Alain Delon played sociopathic Tom Ripley with charm and chilling calculation. Plein Soleil made Delon an international star. He would go on to become an icon of French cinema.

Highsmith’s novel, on which Plein Soleil also was based, was published only five years before production. The themes of lust, sexual identity, and privilege were advanced for their time, even if they were slightly downplayed in the film. Watch it for Delon’s performance and captivating good looks, and for the Hitchcockian suspense story.

C’est Arrivé Près de Chez Vous (Man Bites Dog)

(Directed by Rémy Belvaux, André Bonzel, and Benoît Poelvoorde. Belgium, 1992)

You might have to stop and remind yourself that this is in fact a mockumentary. Man Bites Dog walks the razor’s edge between deeply disturbing and quite funny. Which side it falls on depends upon the viewer’s awareness that the seemingly realistic serial killer doco is a farce. In that way it’s a strange exercise how information can change your perception.

The camera and skeleton crew follow around a sociopathic career criminal, who gives a nonchalant tour of his methods and techniques. These include increasingly nihilistic acts and diatribes until, not to spoil too much, the crew themselves become implicated. Watch for dark comedy kicks, and for a great example of how to make a thought provoking film with a minimalistic approach.

Les Vacances de M. Hulot (Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday)

(Directed by Jacques Tati. France, 1953.)

Language is almost absent from this gentle comedy, except for in the ambiance. It’s easy to follow, whatever your level of French comprehension (or utter lack of!). And Jacques Tati’s style and humor are like nothing the world had seen before. Wes Anderson used his work as a visual touchstone for The Grand Budapest Hotel, and Tati was acknowledged by the Academy with an Oscar nomination for M. Hulot’s screenplay.

The story is simple and unpretentious: a bumbling man vacations at the beach. The visuals, the acting, and the humor are understated, yet somehow bursting with panache. Tati, like the great Charlie Chaplin, wrote and starred in his film in addition to directing. Watch it for Tati’s charming performance, and to feel uplifted about the ultimate silliness of life.

Les Triplettes de Belleville (The Triplets of Belleville)

(Directed by Sylvain Chomet. Canadian, Belgian, French and English co-production

2003.)

Like Les Vacances de M. Hulot, this lighthearted ride is easy to get through without subtitles or French language skills. And in keeping with the strong traditions of Canadian animation, Belleville has a distinct visual style that sets it apart from the dominant tropes of American cartoons.

The song “Belleville Rendez-vous,” a throwback to singers like the Boswell Sisters, won an Academy Award. The joy isn’t just in the music, though. It’s in the way the characters relish playing it. Three old ladies eating frogs and hammering out tunes with spoons on an old bicycle wheel–that’ll make anyone dance. Watch for a smart and upbeat diversion, and a refreshing take on what animated film can look and sound like.

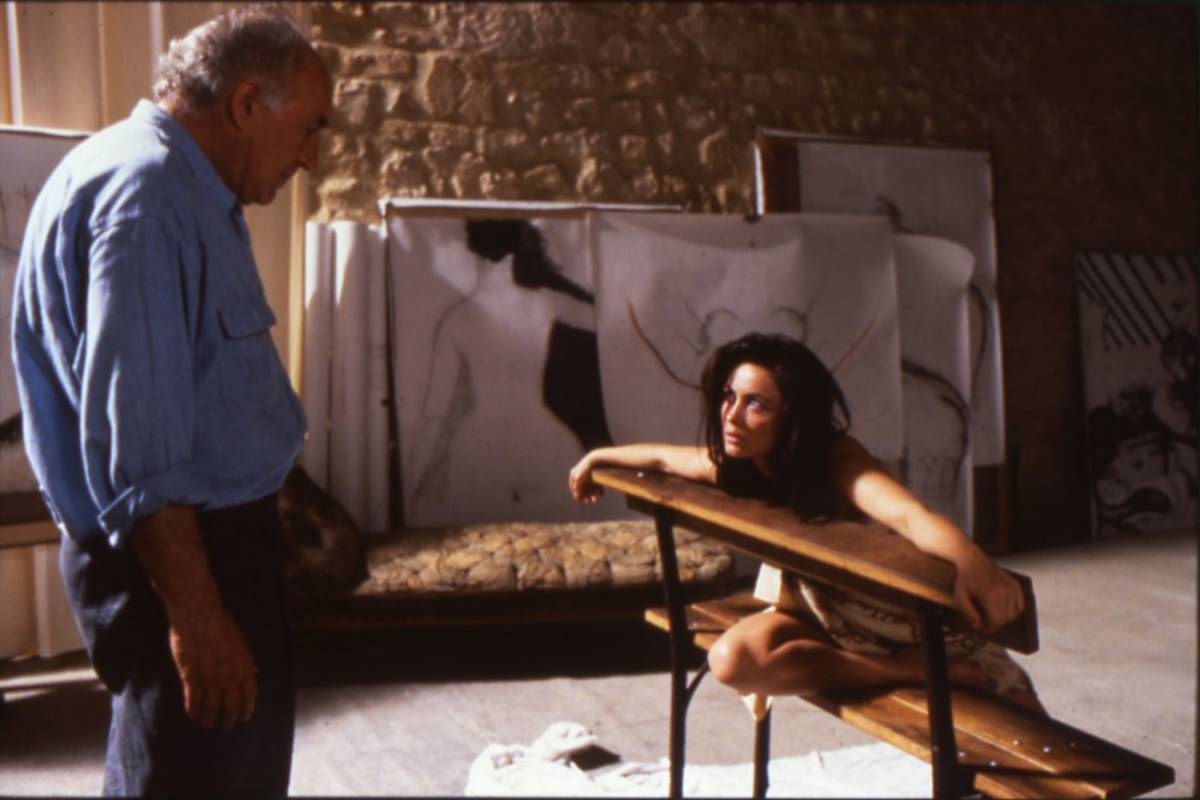

La Belle Noiseuse

(Directed by Jacques Rivette. France, 1991)

One of the greatest movies ever made about the creative process, Jacques Rivette’s patient opus explores the antagonistic, semierotic connection between painter and muse. The film is an exercise in sensual experience. Long takes rich with tactile sounds–the scratch of the artist’s pen, the shuffling feet on the studio floor, the clinking of glasses and paintbrushes–add a painterly texture to this 4 hour escape into the French countryside.

Rivette’s use of frank, extended nudity challenges the viewer to think beyond ordinary notions of arousal. The painter/muse relationship is not, after all, merely a sexual one. Or is it? Whatever agony lies beneath the magnetism, La Belle Noiseuse attempts to draw it out. Watch for the sensuality, and to stimulate conversations about the nature of art.

Maîtresse

(Directed by Barbet Schroeder. France, 1975)

This is a captivating portrait of the double life led by a Parisian dominatrix, through the eyes of a man who becomes involved in her practice. This X rated shocker’s claim to fame is that the dom’s ‘victims’ (read: clients) were portrayed not by actors, but by real masochists. And the torture they undergo on camera, including one man having his penis nailed to a wooden board, is not at all staged.

A word of caution for the animal sensitive, however: there’s a horse killing on camera that’s also real. This movie straddles the line between art and exploitation the way the titular character straddles the dark and light worlds of madonna and whore (as well as one of her clients, whom she rides around her dungeon like a horse). Watch to indulge your BDSM curiosity, and for an early performance in the career of Gérard Depardieu.

Trois Couleurs: Bleu (Three Colors: Blue)

(Directed by Krzysztof Kieślowski. Polish, French and Swiss, 1993)

The strongest and most lauded of the Polish auteur’s Three Colors trilogy, Blue centers on the emotional seascape of a grief stricken woman. Juliette Binoche’s intuitive and brittle performance will redefine the effects an actor can have on your heart. She’s tender and strong, beautiful and pitiful, fierce and utterly empty all at once. Every note is pitch perfect.

Kieślowski couches Binoche’s tour-de-force performance in a wash of visual ambiance. The palette blurs at the edges, soothing and softening the turmoil of the central character. In all Three Colors films, the camera builds an atmosphere you never want to leave. Watch for the emotionally stirring effects, and as a gateway to rest of the excellent series: White and Red.

Timbuktu

(Directed by Abderrahmane Sissako. Mauritanian production in French, Arabic, and Tamasheq, 2015)

Set in neighboring Mali, the story explores the onset of Islamic jihadism in a peaceful desert village. That a story about such senseless violence can be presented with such gentle beauty is a testament to Sissako’s artistic eye. The intimate, personal narratives set against wide, zenlike shots of the desert all place you in the scene and make you feel like you know these people.

The West African music is in perfect step with the story and the visual tone–peaceful, simple, it makes you feel that life is ultimately good. The jihadists will never understand that, but the viewer is in on it. And jihadists can never kill it. That’s the hopeful message of Timbuktu. Watch for a relaxing draught of beauty, and for an African-Islamic perspective on jihadism.

Rififi

(Directed by Jules Dassin. Made in France by an American, 1955)

It’s any wonder Rififi feels like such an American noir caper. Jules Dassin made this film in France after being blacklisted amidst Hollywood’s Mccarthyism. Dassin had been a member of the communist party in the ‘30s. So Rififi gets the best of both worlds: the French gangster style that would appear again in films like Le Samouraï, and the slick American nihilism drawing from postwar noir like The Postman Always Rings Twice. You can even feel Rififi’s diamond heist ripple effects in more recent hits, like the Ocean’s 11 franchise.

This is the film that arguably created the modern heist caper as we know it. Or so said the late Roger Ebert. Watch it for the sustained suspense (just try not to break a sweat during the safe cracking scene!) and the old fashioned thrill of the chase.

Les Yeux Sans Visage (Eyes Without a Face)

(Directed by Georges Franju. France, 1950.)

If you’ve ever wondered what it would look like to see a Mystery Science Theater 3000 style mad scientist movie that’s actually good, Les Yuex Sans Visage is for you. Misbilled as a horror/exploitation flick, the story has enough poetry and meditation to give it substance beneath the relatively moderate creepiness.

The story is what you’d expect: mad scientist tries to repair his daughter’s face, burnt by a car accident, by killing innocents and stealing their faces. It would be good for a laugh if the image of the faceless girl’s mask and the tenderness of her inner conflict weren’t so arresting. Watch for the memorable visuals, the spooky ambiance, and the poetic macabre that flirts with campiness but never breaches it.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.