Heavy spoilers for The Night House to follow.

As it’s horror season, it’s only fitting that movie nights in with my brothers feature horror films. Well, not all the time, since I am the biggest wuss there is, but there is much to be enjoyed in a genre film that I sometimes can’t resist, even if my mind hates me later when I can’t sleep at night. I didn’t get a chance to see David Bruckner’s The Night House when it was first released in cinemas, but now that it’s made its streaming debut, I finally got to see if all the hype on social media was well-earned.

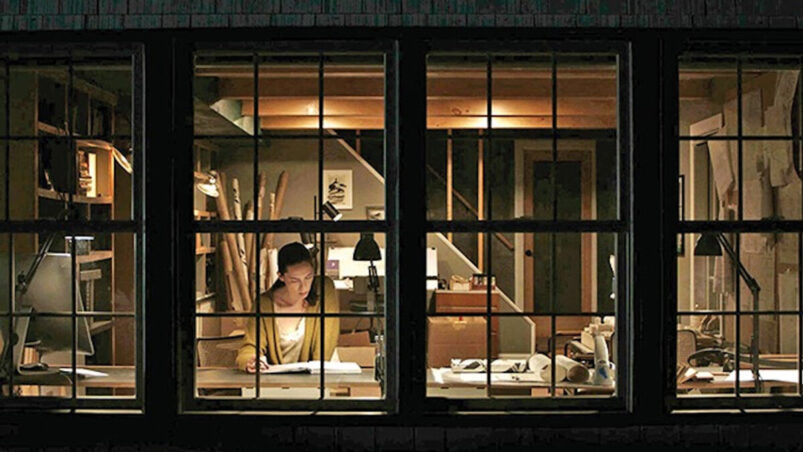

It is, though surprisingly there is some division between the critic and audience scores on Rotten Tomatoes. The detractions given about the film are that it’s a bit slow and confusing, and viewers found the ending disappointing. I have been privy to truly slow films, and The Night House isn’t that at all. It may be what we describe as “slow burn,” but the tension is so well-crafted, and Rebecca Hall’s performance as Beth helps steer every single moment of the film. Hall is one of my favourite actresses, and she is mesmerising to watch here as Beth. She feels like this ticking time bomb, donning a mask dripping with sardonic derision to hide the pain she’s feeling upon her husband’s death, threatening to explode at any moment.

For Beth, Owen was the bright spot in her life, the person who kept out the dark, depressive thoughts. What drives so much of her pain is that his death comes as a complete shock to her, for he took his own life – a gun in the mouth while out on their boat in the middle of the lake. Beth returns to work to settle some admin matters, and her abrasive turn with everyone makes it clear that she hasn’t come to terms with his passing. Every interaction she has heightens immediately into conflict, as we see her struggle to do the socially acceptable thing and keep mum about his passing.

When a parent comes to meet with her about a bad grade (she’s a teacher), Beth makes it abundantly clear that she couldn’t care less or give two hoots about propriety. The parent tries to guilt her about the personal day she took without awareness of the context, and Beth drops the bomb of her husband’s death in her lap. It made me think about how we deal with personal tragedies in the space of work. We don’t speak of what has happened to us because that’s unprofessional, and we are meant to lock away all our inner agonies until the work day is over. Colleagues want to ask but they don’t, because death is uncomfortable, and we skirt around instead of confront.

But not Beth. When she’s at a work outing later on, she pours out her frustration about Owen’s suicide. We see how discomforted everyone at the table is, since she’s bringing dark realities into a space of levitous drinking. Death is an abject thing, and suicide even more so as it involves a darkness we cannot even fathom. For Beth, it is agonising because she never knew that nothing was haunting him. So she burrows her way through his things, searching for answers. She finds copious house plans, with mazes and ambiguous notes about “tricking” something. She also finds plans for a reverse house, which is confusing since she can’t make sense of anything.

As she looks for clues, she starts dreaming and sleepwalking while she’s at it. The transition from reality to nightmare make up some of the scariest parts of the film. There is one moment where she is going to sleep peacefully on her friend Claire’s lap, and just as she does she is jerked into her dreamscape, with Ben Lovett’s score making everything absolutely nerve wrecking. The silhouettes of nothing haunt her, chase her, and as she wanders through this nightmarish world, she learns more about Owen, and the darkness he kept from her.

This is where the audience would start to feel a bit lost. The perception is that the film is about depression and grief, so the haunting and nightmares she experiences are all a result of her psyche trying to comprehend Owen’s loss. However, why all this talk of trickery and the occult? Why did Owen build a reverse house? Her investigations lead her to the bookshop where he bought the books on the occult, and spots the woman that he has photographs of in his phone. There just isn’t one woman though, there are dozens of them – she sees them in her dreams, unnamed women with an uncanny resemblance to her.

At this point, our food delivery came, so my brother and I paused the film to get the food. As we unpacked and settled down to eat, we mused over what exactly the film was at this point. “So, he’s a serial killer,” my brother said as he casually munched on some fried prawn crackers. I nod: “Well, yes, appears so. Nothing was haunting him, and he tricked it by murdering women who looked like Beth. He couldn’t take it so he took his own life.” I considered this nugget of information as I tap danced my spoon on my soup, before turning to my brother: “But I thought this was all in her head. That the horror is about darkness and grief.” He shrugs and says, “Why not both?”

I guess the question isn’t whether or not Owen is a serial killer, or if it’s all in her head. The essence here is that there was a side to Owen she wasn’t privy to. He built a reverse house to keep her away from that darkness, and hid the bodies of the women in said house. While their house together is beautiful and perfect, the reverse house is incomplete and in shambles. Not everyone can come to terms with the darkness that plagues them, so Owen wore a mask for Beth, until he couldn’t anymore.

In some ways, Beth is more confrontational when it comes to her own abyss. As she comes face to face with nothing at the end of the film, which has become the embodiment of her husband, she contemplates giving in to the void of death. There is more confusion here, regarding this entity of nothing, and what it represents – is it a demon, or death? Once again, she could be facing off with her inner demons, or with death who has waited around to claim her all these years. Whichever it is, as Beth considers diving into the abyss, Claire calls to her from the dock, before swimming out to her in the middle of the lake.

In the end, Beth chooses to wake up for her friend, she chooses the light of life over the darkness of death. That doesn’t mean nothing isn’t still there, as we catch a glimpse of it in the daylight before it disappears, however, it doesn’t have power over Beth anymore.

So the confusion about The Night House emerges from the difficulty faced in pinning down exactly what this film is. Is the horror psychological or supernatural? What exactly is the entity that haunts Beth? We seem to have forgotten that the best kinds of art possess indeterminate spaces like this, where the story and horror imagery is suggestive, and the viewer is left to determine what exactly these spaces are. In a world where we can simply google the answers to something, it feels frustrating to not know. But the best kinds of horror aren’t afraid to cavort about in spaces of ambiguity, and, sometimes, that makes for a most rewarding viewing experience.

READ NEXT: 20 Best Supernatural Horror Movies of All Time

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.