Four episodes into the miniseries, and in ‘The Happiness Of All Mankind’ the vast, visceral horror of the Chernobyl disaster is beginning to fade, leaving only the grubbier horrors of the cleanup. This isn’t a case where the cure is worse than the disease, but it still tastes pretty bloody foul going down.

The first and foremost example – which, really, would be enough on its own – is the scorched-earth tactics applied to the contaminated area. Our viewpoint on this comes via a young man who’s drawn the short straw. Rather than the relatively wholesome pursuits of tearing up the topsoil or dropping Agent Orange on the trees, his job is to go around putting down all the animals.

Even though the episode opens with a cow being shot, his victims are primarily dogs – adorable little woof-pups, and you can bet ‘adorable’ was actually on the casting description. In most other media productions, any of the beasts could take pride of place as the protagonist’s faithful pal, or getting kicked by the antagonist to show they’re properly evil. Here, they’re being purged to prevent greater harm, as if to encapsulate how upside-down the situation is, how in this time of unimaginable crisis all the rules are straight out the window.

The episode title, ‘The Happiness Of All Mankind’, comes from this plotline. It’s quoted from one of the ubiquitous Soviet propaganda banners which now seem terribly on-the-nose, especially hanging over the grisly work of the dog squad. Work which, remember, is in service of preserving life on earth. Come the end of the episode, our viewpoint youth is as visibly jaded as his Afghanistan-veteran squadmates.

With this in the foreground, it’s understandable that Lyudmilla’s doomed baby is kept entirely offscreen. We’ve known it was doomed since we first heard it existed, but when the moment finally comes we hear it as a drawn-from-a-hat example of the human cost. All we see of Lyudmilla is the beginnings of her labour, then her catatonic in the aftermath.

On the face of it, it’s an odd choice of self-censorship. We did of course see the first responders having been rendered full Eraserhead-baby by radiation poisoning in the last episode. But to actually show a newborn like that – as twisted and damaged as modern prosthetics can manage, and they can manage quite a bit – against the backdrop of ‘The Happiness Of All Mankind’ it doesn’t seem like it would add anything. It would be bleak for the sake of bleakness, and there’s already plenty of that to go around.

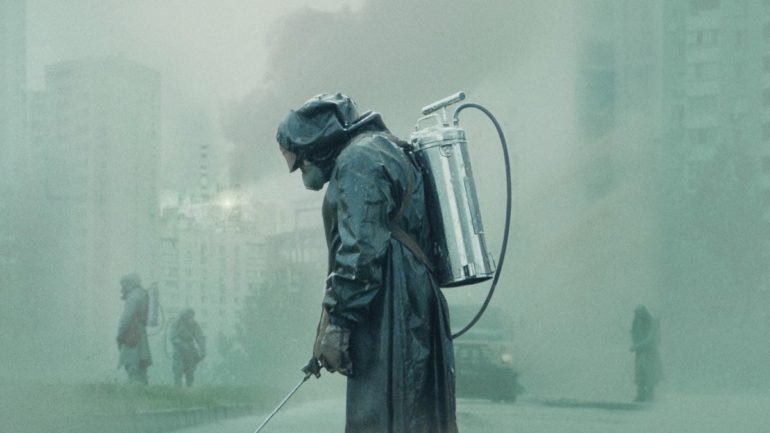

Chernobyl has mediated some of its bleakest moments (stiff competition, obviously) with genuinely nail-biting tension, often enough punctuated by the maddening clicking of a Geiger counter. This episode sees another sterling example, not as claustrophobic as the tunnels sequence in episodes 2 and 3, but still intimately horrifying. We follow the, ahem, ‘bio-robots’ who clear the debris from the most dangerous roof in the world. They can only stay up there for 90 seconds on the trot, and the excellently composed tracking shot reminds us all just how long 90 seconds can last.

Up until now, the fact this is all happening in the Soviet Union has been largely window-dressing, but it’s in ‘The Happiness Of All Mankind’ that this undercurrent finally bubbles up to the surface. The show finally addresses the fact that Soviet-style coverups and secrecy didn’t just poison the response to Chernobyl, but were what made it possible in the first place. The reason? Simply not wanting to admit their reactor design was a bit crap.

More than any dictator ranting and raving, this is the dingy side of authoritarianism. Caught in whatever double-bind is provided, people are obliged to fudge things, declare ‘that’ll have to do, it’s Friday afternoon’, and then, all of a sudden, thousands are dying in agony. While there was nothing else on quite this scale, the grim history of the Soviet Union is full of self-inflicted catastrophes like this.

It’s also full of the other sort, of course – and the cold open literally sees an old woman giving a potted history of them, from the civil war, through the purges and the Holodomor, the whole adventure of the Second World War, and finally this fresh hell. As if to complete this bleak Soviet picture, there’s an encounter with a KGB chief, and, again, the cruelly ironic phrase on that banner, ‘The Happiness Of All Mankind’.

The Soviet Union’s been providing go-to villains for Western media ever since we finished off Hitler, but works like this, that dig down into the real horror of its apparatus as a state, are few and far between. A lot more so even than those looking at Nazi Germany – there is no Soviet equivalent to ‘Downfall’, for instance, no iconic sequence of Khrushchev exploding in fury. Between the excellent The Death Of Stalin in 2017, and now Chernobyl, it’s as if some unknown restriction has finally been lifted on the subject.

(Chernobyl seems to be taking at least one cue from The Death Of Stalin, casting Ralph Ineson as a craggily Northern General in very much the vein of Jason Isaacs’ Zhukov, to say nothing of the occasional pitch-black humour.)

Leading into next week’s finale, there’s a similar situation in play. Legasov is scheduled to speak at the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna, giving him a golden opportunity to break the iron curtain of silence around the flaws of Chernobyl. But if he does, there will be consequences. The Soviet Union, remember, would have sent you to the salt mines for saying, for instance, ‘Gorbachev’s a dick’, so what awful punishment they’d issue for airing their dirty laundry in public doesn’t bear thinking about.

As if to make it more excruciating, Legasov’s well aware of this, particularly with Shcherbina and Khomyuk perched on his shoulders making their cases. Khomyuk, as a scientist, wants the truth out there. Shcherbina wants him to keep schtum, not simply in his role as a party apparatchik, but also for Legasov’s own sake, having grown close to him over the course of the miniseries. This is why I didn’t say ‘perched on his shoulders like his own personal angel and devil’ above – it’s by no means that simple.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.