In 1990, when I was eleven years old, my father suggested that I join the Boy Scouts of America. I immediately said no. He countered with the suggestion that I should at least go and experience what it was that I was saying no to. This was a reasonable compromise. What I discovered were children marching around in military-style uniforms covered with “merit badges,” carrying flags with the kind of reverence you might expect from the crucifer leading the procession in church. This was too much America for me, even as an eleven-year-old, and I declined my father’s offer to pay the fees, saying I found the experience disgusting.

Over the next three of four years, I watched films like Full Metal Jacket, Platoon, Apocalypse Now, and Born on the Fourth of July and felt validation in my resistance to the child military machine. By the time recruiters came around to sign up children in my high school for the adult military machine, they had no chance with me: though I had no specific plans for the future, I knew I wasn’t part of that America.

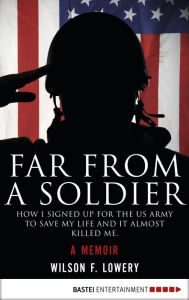

Part of what I found so engrossing about Wilson F. Lowery’s memoir, Far from a Soldier: How I Signed Up for the US Army to Save My Life and It Almost Killed Me, is that by the end of the book, the author and I seem to be on the same page, ideologically speaking, but we are led there by very different paths. Whereas my disgust with the Boy Scouts and grim cinematic experiences led me (along with a general sense of pessimism) to oppose an increasingly bellicose America which was wearing out the warpath by the time I was in my mid-20’s, Lowery, a guy about my age, from a small town not far from where I’m from, becomes just as disgusted with the whole machine, but he makes his way to this perspective from the inside, his experience firsthand.

Far from a Soldier begins with Lowery looking back, identifying what is, perhaps, the greatest difference in our perspectives: his emerges alongside a heavy dose of shame.

“At some point during the day, without fail, I feel completely ashamed. It doesn’t matter what I’m doing, where I’m situated, or what time it is. Something always seems to pass by me. A shirt. A person in uniform. A gun-supporting bumper sticker. A magnet made in China, supporting our American troops. During these moments, I wish I were dead. Or at least living alone in a town where no one knows my past. Instead I’m stuck here in this strange skin of mine, living with my decisions and my regret, always carrying an immense sense of shame.”

What we discover in the pages that follow is that everything in Lowery’s life had told him that there was only one America, the America of flags and veterans, of mom and dad, of small town parades and baseball games, of apple pie and family barbecues, and that the authority of this America depended on fear, deference, obedience, and sacrifice. This was an America he could only let down. He felt he had done so already when he left his hometown and, just after 9/11, had drunk and drugged himself into a Chicago emergency room with acute pancreatitis. So the prodigal returned home, only to pack off shortly later to boot-camp in the US Army, slated already for Special Forces.

There are three characteristics about Lowery that contribute to the clash between the Army and the young private: his empathy for others, his imagination, and his refusal to be broken. He identifies with the young men forced to wear pink vests, the Army’s way of humiliating them, symbolically emasculating them, and marking them as “high risk” in terms of mental health all at once. Then, during rifle training, after excelling at shooting the closer marks, Lowery, taking aim at a 200-meter target, has what comes across to the reader as nothing less than a vision:

“Instead of seeing a target, I saw a man walking with a helmet and rifle slung over his shoulder. It was a nice, clear day and no one was around. He appeared to be out on a stroll, maybe taking a much-needed break from the hellish fighting he’d just witnessed. He was enjoying his life and his solitude when my finger pressed the trigger, my bullet striking him through the outer layer of his jacket at more than a thousand miles per hour. It entered his body just above his second rib, piercing his lungs and exiting into the dirt behind him. He dropped to the ground, gasping for air, images of his life flashing before him as death welcomed him home.”

Not long after this experience, Lowery refuses to continue with training. The narrative turns to an exploration of the Kafkaesque battle of a Private Nobody against the bureaucratic machinery of the US Army; the psychological warfare between Lowery and his superiors; and, perhaps most interesting and disturbing of all, a never-ending war between Wilson F. Lowery and himself–a war that mires him in depression and substance abuse, turns his relationships upside-down, and nearly wipes Lowery from the earth altogether. He survives, though, as the subtitle states, it does almost kill him: his refusal to be broken, his sense of self, or whatever you want to call it, helps him withstand the pressures pushing down on him from without, but those from within almost tear him apart.

For all the heaviness of the subject-matter, Lowery’s tone isn’t light, exactly, but it does retain a sense of innocence; he almost stands outside himself and observes at a distance the ridiculous antics of the drill sergeants, for example, or the dark comedy of explosive diarrhea in the military ER after having a bottle of pills pumps out of and the charcoal pumped into one’s stomach. Such a tone contributes to the sense in which the memoir can be read almost as a coming of age story. The book’s structure, integration of letters, use of dialog, and observations result in a highly personal story that you don’t want to put down, as well as one that incisively examines the disturbing pull of American nationalism on an individual psyche.

Lowery begins his journey still very much an emotional, sensitive, rebellious kid, one with enough self-awareness that he realizes he can’t persist with the life he has let himself sink into but not enough to make a real decision about the kind of life he wants to live. He ends the novel having finally begun some serious self-examination, discovering that his feelings of betrayal, failure, inadequacy, and shame have as much to do with his family relationships as they do with his relationship to the Army. Further, he has come to the realization that an authority, national, familial, or otherwise, which demands blind obedience and thoughtless reverence in order to sustain a false dream, is an authority that deserves resistance. But these discoveries do little to wipe away the pain of the necessary self-destruction required for growing up.

So what meaning stalks behind us as we trek these alternate paths towards varying degrees of political pessimism? It probably means that Wilson Lowery is a better person than I am, but I hope it also means that the divisive, mercurial “American Dream” is dying. But if the latter is happening, then I’m a little concerned about whatever this obvious fiction is about making “America great again” that’s increasingly replacing it. Maybe Lowery is right: maybe we will only really see ourselves through recognition of our shame. Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be a lot of that around these days.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.