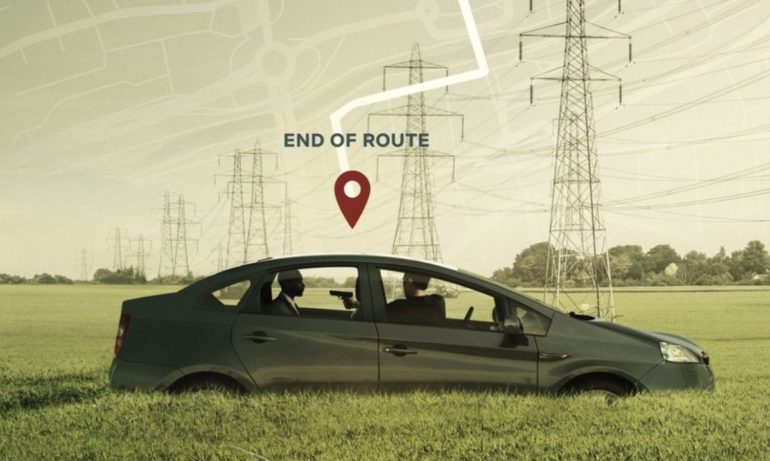

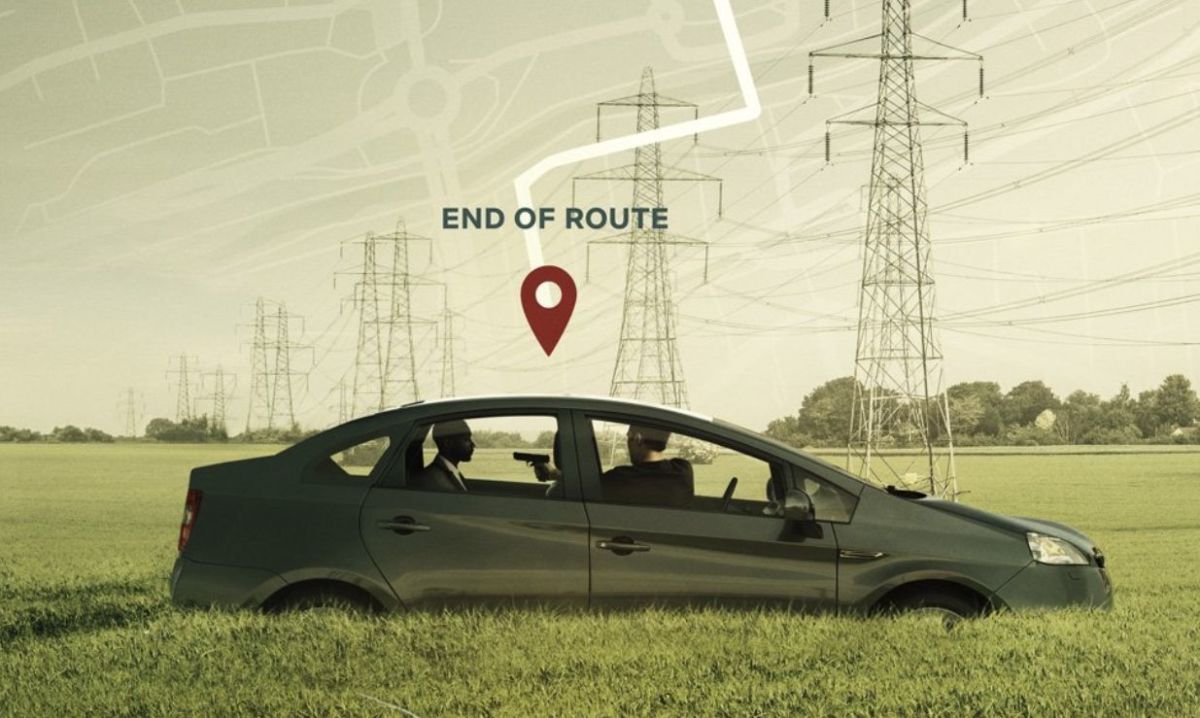

‘Smithereens’ has us following a man who kidnaps another man at gunpoint. Not your traditional protagonist maybe, but we follow him anyway. There’s a moment in Hitchcock’s Strangers On A Train when the baddy drops a vital MacGuffin through a drain cover, we see him desperately trying to pick it out, and despite themselves every audience the film’s ever had does, on some level, want him to succeed.

The short version: Keep your eyes on the bloody road.

The longer version: In a radical departure from Black Mirror’s five-minutes-into-the-future idiom, ‘Smithereens’ is explicitly set in the futuristic, far-off year of 2018. That is to say, last year. This isn’t to its detriment, though, quite the opposite. Like the very first episode, ‘The National Anthem’, ‘Smithereens’ features no fictional technology, it’s all the kind of social media stuff you could probably click onto right now.

‘The National Anthem’ was a split hair more realistic in this sense, in that it stuck rigidly to using actual websites and services. ‘Smithereens’ will refer to YouTube and Google, but has also called its standard-issue social network ‘Smithereen’. This is possibly because Facebook has a mean legal team, but it makes sense in that it could stand in for any of the time-hole social networks that send constant notifications to tell you somebody gave you imaginary internet points.

(The name ‘Smithereen’, too loaded and distinct for any real social network, is likely a reference to the concept of social atomisation, a process which the information age kicked into overdrive.)

However, ‘Smithereens’ presents a more realistic scenario, certainly one that has the ring of familiarity. Thus far, no politicians have been blackmailed into screwing a pig live on Twitch. On the other hand, we’ve all seen serious but localised crimes turn into hot stories and become the talk of all the world’s media. These are usually America’s semi-regular mass shootings, but in the gun-phobic UK, a man waving a pistol around would get the same traction, particularly with the juicy twist of demanding to talk to Topher Grace’s Elon Muckerberg character.

It’s Andrew Scott, he of Sherlock and Fleabag, playing the man with the gun, so obviously the whole episode turns on his performance. Everyone else, the police, the hostage, even Muckerberg himself, are little more than props in his one-man drama, so he really has to sell it – and, full credit, he does. Scott presents us a genuinely broken man, tentatively holding it together for a while but rapidly breaking down as the episode goes on.

It culminates with him finally managing to get Muckerberg on the phone and deliver a tearful monologue. Just how did Smithereen play into the untimely death of his fiancee? As it turns out, there’s no insidious conspiracy at work, at least not beyond the usual grubby business of running a social network. Scott’s character checked his phone while driving, crashed the car, and killed three people. That’s it, it’s a lapse which could happen to anyone, and it’s prompted this whole bloody drama – which is by then being monitored by the security services of two nations, and has become a media circus.

The full horror of it all is driven home by the ending montage, when the news item becomes yet another of the endless updates on phones all over the world. And, true to form, we see at least one guy distractedly checking it while he’s behind the wheel and in command of a two-ton assemblage of metal, glass, and combustible liquid. The old saying is ‘those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it’, but this suggests a series of events yet crueller even than that, of the act of remembering the past itself causing the repetition.

David Sims of The Atlantic called the episode ‘a story about demanding accountability’ from the tech giants. This is a fair reading, in that when exposed to the sheer might of the industry, most people will have the same knee-jerk ‘can’t something be done?’ reaction, but what kind of accountability could possibly have prevented anything we see happening onscreen? Smithereen already has the power to tap Scott’s phone and figure out his identity in moments – information which, being a good, law-abiding firm, they promptly share with the Metropolitan police and the FBI. Accountability is not the issue here, nor the solution.

This also ignores the culpability of Scott’s character. He notes, quite rightly, that social media is tailor-made to be as addictive as possible, to encourage behaviour just like his, but never comes near the depths of self-indulgence needed to suggest that those deaths were anything other than his fault. Black Mirror was never simply a tale of ‘ooh, scary scary technology’, it was always about how people interacted with that technology, and the unforeseen consequences that this brings about. In this case, people died, people were hurt, and it could all happen a dozen times again tomorrow.

Still, the familiarity of this kind of thing, a much-publicised gun threat, can’t help but breed contempt. And there’s something similar going on with Black Mirror, which was itself once a departure from pretty much anything else out there. It was the same acerbic look at media-driven culture Charlie Brooker spent years honing with Screenwipe, interpreted through a Twilight Zone-style anthology drama. Now, five seasons in, it simply can’t be as shocking and immediate as it once was, and if anything’s missing, it’s that, the sense of sheer alarm.

Talking about his role in Jordan Peele’s Oscar-winning horror film Get Out, Daniel Kaluuya (who first came to international prominence in Black Mirror) made particular note of Bradley Whitford’s character claiming “I would have voted for Obama a third time” to sell himself as a right-on non-racist. (By Whitford’s own account, that may have been true to life.) Per Kaluuya, after the film was released, that sort of thing became “I’ve watched Get Out three times”.

Perhaps something similar is true of Black Mirror – that it takes powerful, genuinely scary social forces, and seems to place them into the safe little box of quality drama. It makes us falsely believe that ever-evolving technology is something easily understood, something to be digested in an hour-long chunk and then done with.

Once upon a time, anyone who thought the security services were tapping your phone was dismissed as an alarmist crank. Now, the fact that the security services and the tech companies are always listening in is common knowledge – as in the meme of people speaking directly to the FBI agents monitoring them – a detail dropped quite casually into ‘Smithereens’.

Black Mirror is the same thing on a broader scale. It meant to warn us about this looming threat, and instead practically made it a member of the family. Doubtless when Apple finally come to round us all up and tattoo barcodes above our genitals, someone will guffaw “It’s just like Black Mirror!”, and who’s to say they’ll be wrong?

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.