It’s 2018. A24 is just beginning to peak, putting their name on the majority of successful arthouse films that are granted mainstream release. They release hits like Good Time, sleeper hits like Enemy, and Oscar winners like Moonlight.

So you’re looking online for something to watch and you see showtimes for Hereditary. The A24 logo suggests something promising awaits but the trailer, while certainly frightening, displays what may be just another ghost movie. If you’re a horror fan who attends theaters frequently, you may be too tired for another Insidious or Conjuring. But reviews amongst critics and viewers are united in rave for this unknown filmmaker’s feature debut. So you decide to watch the film.

But instead of another horror romp that sacrifices character work for jump scares and one-liners, you are given a somber meditation of grief, the never-ending haunting force of mental despair, and an intertwining between family drama and occult horror. Hereditary begins with a faux clipping of an obituary for a character who, although never being depicted as alive, has so much impact on the rest of the film that a case could be made for her being the main character. From there, we have a funeral between Toni Collette’s high-strung protagonist, her apathetic son, strange tongue-clicking daughter, exhausted husband, and a procession of people she’s never really met, showing the extent of her mother’s secretive and suspicious behavior.

From there, we see a multitude of long takes, many of them quietly zooming onto the speaker, usually Collette, as the family processes their grief, usually from different rooms in their house, alone. And thus begins a string of events that upon each viewing seems less and less coincidental, that leads to more tragedies, subsequent hauntings, and psychological unravelings.

You know, as you exit the theater, that you will certainly rewatch the film.

Thirty-six years old, approved and interviewed by Martin Scorsese, and three audacious and unique features with mainstream releases Ari Aster refuses to yield to cinematic trends; his style is distinctly his own.

For example, his film Midsommar, which was released in 2019 and made back-to-back with Hereditary, also features a grieving female protagonist (played by Florence Pugh) who, like Toni Collette in the former film, hides her psychological duress from the people she loves. But this time Aster is less interested in the family drama, but gives us an anti-romantic breakup movie instead. He is a dramatic director disguised as a genre filmmaker.

From interviews with Aster, one can plainly see that he is a lifelong devotee of classic films, both within and outside the horror genre, and this is part of the appeal of his films. What makes modern horror effective, especially in a world where many of us feel we’ve seen everything, is a thorough understanding of the cinematic medium and not exclusively the horror genre. 1970s giallo and the slashers of the following decade have their charms, but if I’m watching something made in the past several months I tend to expect a little more. So with both Hereditary and Midsommar, it is delightfully surprising to see the usage of lengthy one-shot takes and the subtle gravity of the performances, particularly for the female leads.

There is a sense of loosely-defined auteurism as well, for Aster manages to be a genre filmmaker and a humanist all at once. In Midsommar, many of the psychological and emotional mappings of the main characters, the couple played by Pugh and Jack Raynor, are based in part on himself and a former girlfriend. Despite this, he manages to not overindulge or alienate his audience. His first priority is entertainment and thematic content.

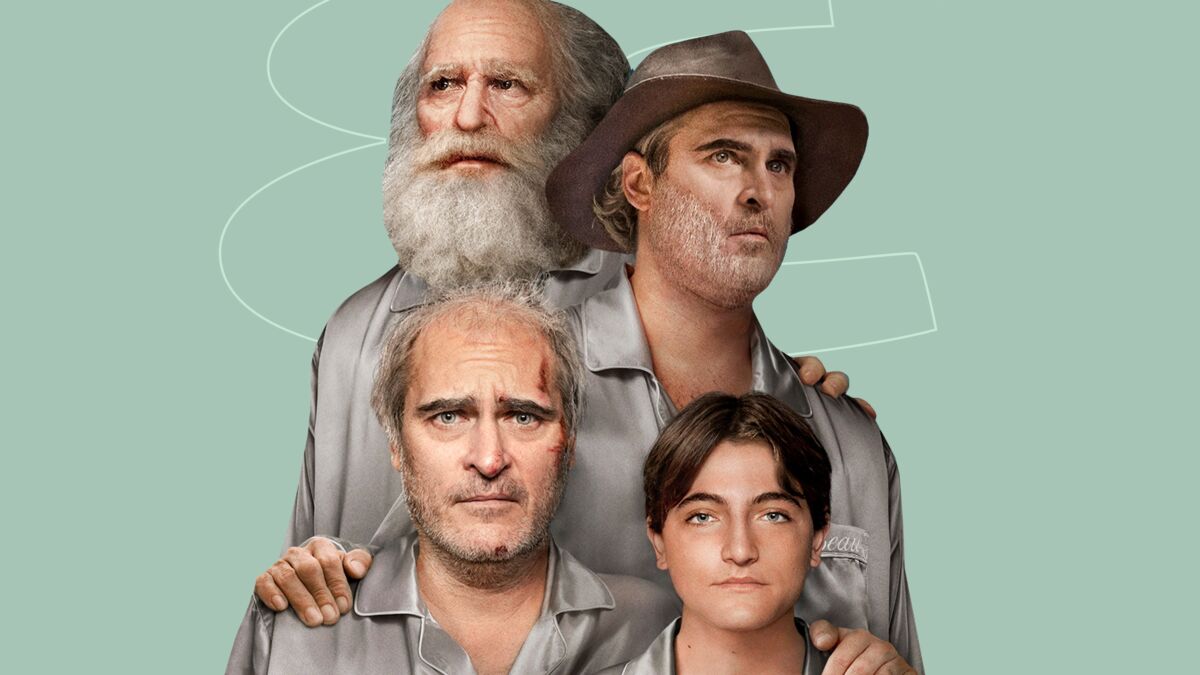

But just this year, Aster released his most divisive film so far, a three-hour epic odyssey titled Beau Is Afraid.

Beau is Afraid follows an easily frightened nebbish man in his forties played by Joaquin Phoenix who, after a series of confusing over-the-phone conversations with his mother, decides it’s time to go home.

There are sequences of pure surrealism that match the likes of early Lynch and perhaps 2022’s Men, that explore the divide between childhood adolescence and adulthood, as well as the wonders and possibilities that are granted (or deprived off) by the simple means of growing up. This is explored through means of surrogate families, stagecraft, animation, and inexplicable imagery that we can only hope to decipher.

From the beginning forty-five minutes at his apartment, however, you can tell that wherever this is, it isn’t our world. People are maniacal and intense; Beau is the right to be afraid. All preconceived notions of how the world works go out the window. And from his messy exit into the streets to crashing a suburban hellscape, and finally making it home, I, while seeing people in my peripheral vision walk out while the film’s still running, saw the best film of 2023 thus far.

Whether or not people reading this wholeheartedly agree with this shift in vision or not, I think it’s important to acknowledge that even if he has failures in the eyes of some individuals, his work to date is crafted with confidence and absolute trust in his own vision. Even naysayers, who think his vision is faux or even terrible, can agree that such prowess is truly all we can hope for from a filmmaker.

READ NEXT: The Best Horror Movies of the 21st Century

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.