Last Monday, my alarm blared with the usually soothing but in that moment rather unpleasant vocal harmonies of Donald Fagen’s ‘I.G.Y.’, unpleasant because it was doing this at 2:45am. The reason for this was that at around 3:15 I was going to have to haul myself into my car, wrap myself around the steering wheel and drive my younger brother to his college so that he could get a coach to Heathrow (and then subsequently fly to New York). I was happy to do it, don’t get me wrong, it will be a valuable experience for him, but sleeping for around 3 hours only to get up again is almost like being blue-balled in slumber terms, I’d had a preview of a decent sleep and little else.

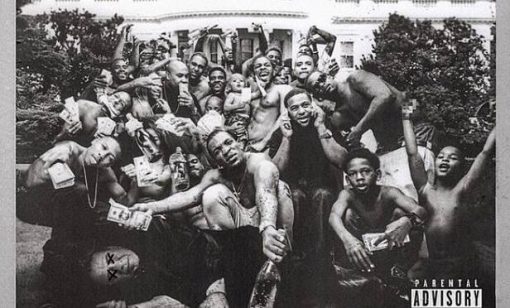

The reason I bring this up is to help you understand the significance of what happened next. When I got back at around 4:30, I rolled back into bed expecting to sleep in until around noon like the teenage me of yesteryear would have on an idle Saturday or Sunday, but when I lazily pawed my phone off of my bedside table at around 9 I saw something that made me completely disregard my need for further sleep, launch out of bed and straight into my office (yes, I have an office). To Pimp a Butterfly, Kendrick Lamar’s hotly anticipated follow-up to his massive 2012 album Good kid, m.A.A.d city had dropped a week earlier than expected. I wasn’t about to let anything as trivial as fatigue stand between me and it.

Reactions are pretty spread when Kendrick Lamar’s name in mentioned, some immediately unleash an onslaught of exuberant praise, others groan, others smile knowingly and others furrow their brow in puzzlement, utterly unable to grasp what the big deal about K Dot really is. I used to be one of those people, I’d heard him feature on a few tracks here and there, I’d heard his muscular, confrontational verse on Big Sean’s ‘Control’, I had a rough idea of him but to me he seemed like nothing more than another ego with a rapper attached. Even when I actually sought out Good kid, m.A.A.d city nothing really clicked, I liked ‘Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe’, I liked ‘Swimming Pools’, I really liked ‘Money Trees’ (but mostly for Jay Rock’s verse) but why were people frothing at the mouth at the very mention of this guy? Once I understood, it didn’t get any easier to explain, but now that To Pimp a Butterfly is here, it is.

The moment I started listening to it that morning, back in bed, propped up by two pillows with my big Sennheisers on, I knew it was everything everyone had hoped for. The disjointed, funky, abstract vibes of opening track ‘Wesley’s Theory’, with production work from Flying Lotus and featuring none other than the legendary George Clinton opened the doors to a colossal musical maze of an album littered with bizarre beats, challenging bars and significant themes, but this was no underground LP that would take years of championing by clued-in hip-hop-heads and hipster pretenders in ‘Dilla Changed My Life’ T-Shirts before it reached any position of wider recognition, this was going to be a best-selling, top shelf album, this was going to clear millions of downloads, sweep award ceremonies and take the world by storm. To Pimp a Butterfly will be remembered as one of the crowning achievements of a new era for African American culture. That is why Kendrick Lamar is so deserving of the praise he receives.

There are two sides to this story, the first being a purely musical one and the other a much broader cultural one. America is going through a period of heightened turmoil at the moment, the scars left by the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice and countless others still feel very raw and more and more voices are speaking up for the injustices that plague the African American community (to say nothing of all the other people that are being persecuted). One the one hand you have John Legend and Common exemplifying the abhorrent disproportion of black incarceration in the USA during the Academy Awards and on the other you have riots raging in the streets of Ferguson and Saint Louis, but more than ever, music has played an instrumental role in making people heard (no pun intended).

D’Angelo, having not released an album in 15 years, put a rush on the release of Black Messiah to make sure that the ideas conveyed in tracks like ‘The Prayer’ and ‘The Charade’ reached people’s ears just as people really needed to hear them. On the day that Darren Wilson was acquitted, damn near every act that had been booked to play in St. Louis that night high-tailed it out of there, except Run the Jewels, who played as scheduled, but not before Killer Mike addressed the audience in a flood of tears and proudly stated that nothing would ever devalue his friendship with his white band partner, El-P. Now with To Pimp a Butterfly, 27-year-old Lamar has gifted the world with an astounding collection of works, bolstered by talent from across the hip-hop, funk, jazz and soul community, laden with classic samples, pivotal cultural references and built around his personal story, a child of Compton who has seen suffering and suffered alike. Perhaps not to the same extent as his idol, Tupac (whose spirit flows through every vein and artery of this album), but enough to lend undeniable weight to every statement he makes from the opening bars of ‘Wesley’s Theory’ to the galling, closing spoken moments of the closing track, ‘Mortal Man’.

The ideas conveyed on the album aren’t necessarily all unifying rallying cries. Rather, some of them are somewhat controversial, not least on ‘The Blacker the Berry’, the single released back in February, which closes out with the line “So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street/When gang banging make me kill a nigger blacker than me? Hypocrite!”. It’s hard to digest on face value, as are some of the statements thrown out in ‘King Kunta’ and ‘Hood Politics’, which could be interpreted as Kendrick regarding himself from atop a pedestal, but taken as a whole, the album clearly promotes black unity, black self-respect and above all else black love.

The first single to be released from the album, ‘i’, was a warmly received, jubilant celebration of self-love set to a well placed sample from ‘Who’s That Lady’ by The Isley Brothers, the album version is different, constructed to sound like it’s being played at a fictional concert which suddenly breaks out into anger, causing Lamar to cut the music and address the crowd. “It shouldn’t be shit for us to come out here and appreciate the little bit of life we got left dog” he says, before breaking into an acapella section, almost a beat poem about loving your fellow man which he appropriately dedicates to Oprah Winfrey. The single version is an infectiously joyful track that it’s easy to listen to without pondering on the wider implications but the album version deliberately makes no such allowances, Kendrick knows he has a captive audience and he says everything he feels like he needs to say, demonstrating a bravery rarely present amongst artists as far on the forefront of the genre as he is. It shows real wisdom.

[Tweet “Kendrick knows he has a captive audience and he says everything he feels like he needs to say”]But even with all that taken into account, what makes Kendrick so special? There are plenty of other MCs and producers out there with just as much, if not more to say, are they not worthy of the same recognition? Well yes, of course they are, talent cannot be broken down into accumulative figures and recognition cannot be doled out like smiley stickers. You might also argue that all of the heavy statements could be little more than a by-product of a glory-hunting star, were it not for the fact that Kendrick has been doing this kind of thing for years, this album could almost be the closing installment of a trilogy, preceded by Good kid, m.A.A.d city and Section.80.

Regardless of how it happened, Kendrick has reached a level of global recognition that practically assures his legacy, and it would have been so easy to be overcome by it as so many rappers before him have been, but not only does he keep sight of his convictions and creative license, he openly confronts the darker temptations of fame, referring to the devil as ‘Lucy’ on several tracks, personifying that very issue. More to the point, the album doesn’t fall into the trap of becoming a celebration of attained grandeur, stuffed to the brim with big label names. Dre and Snoop both make appearances, but in the name of context more than anything else, neither one spits so much as a bar. In fact, the only MC to be given a guest verse is none other than Rapsody, mother of the other great hip-hop album of 2012, her verse on ‘Complexion (A Zulu Love)’ beautifully extols the same need for unconditional love that resonates through so many of Kendrick’s words.

As far as the music is concerned, I find all this extremely exciting. There is no way to downplay, devalue or trivialise the importance of the work being done here, American culture has a long, difficult mountain to climb if all these ingrained prejudices are going to be overcome and music is going to carry on playing a vital role in that journey. With that in mind, seeing an album like this one, an album littered with unusual beat structures, chord progressions, unusual samples and other phenomena that you’d expect to frighten the layman away like a dog being menaced by a vacuum cleaner being so eagerly anticipated and trustingly snapped up by just about everyone is a huge, huge deal. In a fascinating ciruclar motion, jazz musicians, lessoned in the practice that more or less gave rise to sample culture in the first place, are now being influenced by hip-hop and involving themselves with it. Saxophonist Terrace Martin and pianist Robert Glasper both have their fingerprints all over To Pimp a Butterfly and it extends beyond that, I can’t actually believe I’m actually about to say this, but it’s bigger than hip-hop.

Look at Flying Lotus, his music is not easy to grasp and it’s not easy to love, yet You’re Dead! broke into the top 20 of the Billboard 200 and sold tens of thousands of copies in its first week alone, and he’s been selling out shows all over the world. What this means is that there’s a more widespread open-mindedness and trust in artists than anyone realised and labels are taking notice, artists are being offered far greater creative control over their work, albums like To Pimp a Butterfly, far from being anomalous, are fast becoming the standard. Think about that for a second. The underground will always be the underground, it will always take a longer reach to make that step from Dre to Dilla, but the world is changing, hip-hop production is morphing from a complicit machine to a laboratory on a wider and wider scale and Kendrick Lamar is on the frontier of it, his work is cementing a massive, unstoppable wave of change. So if you haven’t already, get yourself a copy of To Pimp a Butterfly and get acquainted with some living history.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.