The reasons why human beings like horror have long been a subject of debate. Studies have found that people who like “dark” movies tend to be well-educated, self-disclosing, and creative. It’s not a far leap to the idea that people who display this constellation of characteristics may also experience some anxiety in their daily lives; horror films are a psychologist-approved means of dealing with baseless, uncontrollable fear.

In fact, the horror tropes that make critics’ eyes roll the hardest address anxieties so deep that you’d need a master class just to cover them outside of that “dark” subgenre. Luckily, you don’t need to go back to school to understand why you like George Romero. You have the Cultured Vultures.

Why zombies?

Any evolutionary psychologist will tell you that humans are not supposed to like looking at dead humans. A quick glance at the popularity of the zombie genre suggests that either this isn’t completely true, or that there’s a subset of people who do, in fact, enjoy watching dead bodies shuffle around. The truth is a little more complicated, but ultimately, it has a lot less to do with corpses than the evolutionary psychologist might assume.

Zombies are naturally a shocking sight. Nobody wants to think about dying, and the idea that you will inevitably join the great mouldering majority and become ugly and stinky is distressing in its own right. But that’s a little clear-cut, isn’t it? After all, death comes for everyone in horror, whether by chainsaw, blunt force trauma, or desanguination. Zombies represent something much scarier: consumerism run amok.

Zombies aren’t just corpses rotting on the hoof. They behave. They have patterns. Because of that, they’re predictable, and their limitations are obvious. They’re not even great threats unless they grow into a population of millions. According to “The Zombie Survival Guide” by Max Brooks, it’s entirely possible to outwalk, out-bicycle, and outclimb a zombie. Aside from the psychological shock of seeing a dead body hop up and start snapping its teeth, zombies aren’t particularly scary.

It is the zombies’ collective action that is frightening. They consume. They don’t need to, of course; their desire to eat is an automatic reaction. Still, its implications are innately horrible. Zombies can never be satisfied. They produce nothing themselves, unless you could count them as roving sources of fertilizer. What else on this planet behaves that way but a consumer?

We human beings have cleverly, and with tremendous innovation, manufactured an age of rampant, obviously unsustainable economic and natural consumption. For proof, have a gander at the garbage dump for any major city. The carbon that we pump into the air degrades our environment and we multiply in our billions until we press the upper limit of the amount of food we can create. We go along to get along, following established patterns of behavior, often not considering how those patterns affect the world around us. Zombies are nothing so simple as a direct fear of death. They’re the fear of the inevitable reckoning of all of modern society’s lousy habits.

Zombie flicks, set in malls and corrupted wildernesses and suburban developments, also represent the fact that the little guy, who’s just fighting to survive, can’t help but answer to mob rule eventually. The likely outcome for a zombie movie survivor is eventual zombification. It’s just probability. The gluttony of the people around him will subjugate his ideals and dreams, and he’ll become a mindless eater, too. The hope of the zombie flick is that this won’t happen if you’re vigilant and brave. You can start over using your wits, your friendships, and your belief in the value of human life. Then, the next time mindless consumerism rears its rotting head, you’ll know what to do.

Why vampires?

Picture Bela Lugosi. He’s a distinguished guy. He has a widow’s peak. He has an accent. He vaaants to saaaahk your blaaahd. On top of all that, and most significantly, he’s a very rich aristocrat. Dracula – Count Dracula – is literally entitled.

The wealthy have always seemed omnipotent to the non-wealthy, and when Medieval peasants invented the concept of vampires, there was very little that an aristocrat couldn’t do. A count or a duke or even a bishop could make mind-blowing decisions about your life. Pope Urban II started the first Crusade, sending thousands of European peasants to pointless deaths in foreign lands, just to make the point that the aristocracy couldn’t mess with him. The nobility were terrifying. Even today, maintaining a class hierarchy requires blood. If you ever find yourself doubting this, consider what is known in America as the economic draft. That is the informal name for the fact that the poorest Americans make up the largest part of the armed forces; the children of wealthy senators and billionaires have no need for the financial incentives or the danger involved in service. Class is inherently monstrous, and it requires the literal use of the poor. No wonder there is an entire horror subgenre based on an unstoppable, immortal, blood-draining, woman-stealing Count.

Even the recent aspirational change in vampirism reflects the gospel of prosperity. In marrying Edward Cullen or Akasha, you, too, could become an educated, sophisticated, worldly, and sexually attractive vampire. You’ll live longer and look good doing it. The hook of the vampire is that they might not actually drain you dry, as they do most of their victims. If they take a shine to you, you could join them as an apex predator and live the good life. It’s better to rule, immune from conscience and endowed with the power to escape all consequence. Recall, however, that vampires are generally tortured beings who may express deep regret or inner conflict at their own existence. The good life is a moral tradeoff, apparently. Perhaps they’d feel better if they gave copiously to AIDS research.

And yet, the vampire legends upon which Stoker based his groundbreaking book were almost always tales of rebellion against bloodsucking eternality. Taking into account current events (in combination, as always, with a spot check on the old Ouija board), it’s possible that we could see a resurgence of this model quite soon. Read Dracula someday. The most compelling hero of that tale, which is rife with commoners who resist the vampiric threat, is a brave, brash woman who knows the train schedules by heart and plays a critical role in bringing down what’s essentially a very rich, very charismatic, very powerful rapist. Sound familiar?

Why psychos?

People with mental health disorders are far likelier to fall victim to crime than to cause it. If you’ve ever dealt with someone in the grip of psychosis, or had to experience psychosis yourself, you’ll know that it’s a profoundly hampering condition that makes any kind of directed action a huge challenge. When we refer to “psychos” here, let’s not make the mistake of assuming that the unfortunate man battling his demons on the street corner is in any way related to this trope.

But psychopaths are a different story. This term denotes people born without the ability to distinguish right from wrong. This unusual characteristic is either a deal breaker or a superpower, depending on whether you’re sitting in a bedroom or a boardroom. Famously, psychopaths tend to do very well in business, but make awful relationship partners. But we don’t have a whole lot of horror movies about CEOs. Instead, we get Michael Myers and Freddy Krueger, neither of whom seems as enthusiastic about next quarter’s profit margin as the glee of a creative kill.

The idea of the psychopath is itself a little frightening. If someone amoral decides to kill you, how could you possibly appeal to them? They do not, and cannot, care about how you feel. Unfortunately, just a little bit of analysis breaks this fear to pieces. Psychopaths could theoretically be manageable as threats as long as you remember that they will always do whatever maximizes value for themselves. If Freddy was just some guy with an underdeveloped amygdala, then you could effectively offer him any range of bribes to get him to leave you alone. He’d be susceptible to rational argument. Somehow, it seems questionable that a movie about the terrifying slasher counting fifties as you nervously wait to see if you’re still worth his time would succeed at a box office.

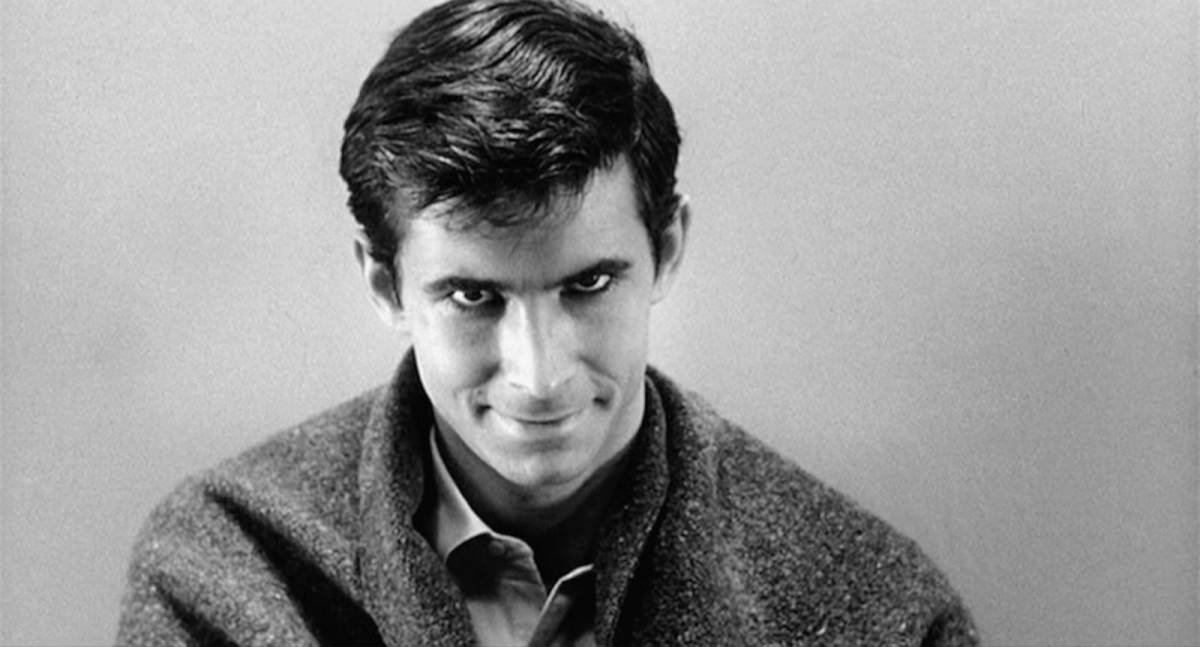

However, Freddy Krueger, Jason Voorhees, Leatherface, and their kin all have something else in common. Freddy is a janitor, Leatherface wields a workman’s tool, and Jason is the child of a working-class family. Even Norman Bates is just a stiff doing his job. Extrapolate even further to more recent, psycho-inspired horror films like The Purge and Saw. The predators in these franchises are the unremarkable and ordinary. The prey: their successful neighbors. Once again, we are slapped in the face with a class anxiety, but this one rises from below. Vampires represent anxiety of upper classes, but psychos represent our fear of the poor. Whenever Jason wields his knife-shaped resentment against entitled summer campers, he embodies the fear that despite all of the viewer’s privilege and safety, someone who should never have been a threat could ruin everything. It disrupts the order of things when janitor Freddy invades the suburbs. The terror of his psychopathy ranks secondary to the fear of the blue collar hiding under that sweater.

Why monsters?

There was a time when people invented monsters in a direct response to the threat of nature. Scylla and Charybdis, for example, are a bunch of rocks situated at just the wrong place next to a whirlpool that might be located off the Sicilian coast. Dragons were an amalgamation of venomous snakes and the lightning strikes that regularly ignited thatch-roof homes. Anyone who does not start inventing sea serpents when floating over a bottomless expanse of water has not sufficiently examined their reality.

But since the second World War, monsters have experienced a shift. The common postwar assumption, in the West, at least, was that lawns could be tamed, that illnesses could be eradicated. The technology that sprang from military research opened an age of miracles and wonders. It also revealed, in spectacular fashion, that nature was never the real enemy. Humankind’s problems are only ever generated by itself. New weapons threatened all life, no longer restricting war to human groups that had decided to disagree. The rise in medical understanding was partially based in horrifying experiments that themselves led to new rules about ethical human testing. In exchange for postwar prosperity, human society collectively and quietly traded in a few morality cards.

The fact that Kaiju like Godzilla and Mothra are artifacts of the nuclear age shouldn’t come as a surprise. Nuclear anxiety in Japan may have taken form first, but all over the world, we fear what science has done to the atom. This is a power that can warp nature, the original source of our greatest monsters. Dragons once frightened us, and now, we miss those regal beasts of air and fire. Look at a picture of a dragon, then Google “Chernobyl radiation pig” and feel your gut churn. People have become so powerful that we’ve learned to twist the scariest thing we used to know and make it meaner, weirder, sadder. Our modern monsters are a combination of fear of ourselves, shame, and loss. We’ve replaced our fiery dragons with a nuclear-powered gila lizard that ultimately just wants to be left alone.

Even prior to the postwar era in modern society, monsters often featured an aspect of human culpability. Consider, for example, the Jersey Devil. This humanoid, horse-headed abomination, which purportedly lives in the Pine Barrens in the state of New Jersey, was cursed by its mother, who rejected it immediately upon its birth. Consumed by resentment, it brutally attacks anyone who enters its range. The Yeti’s greatest desire is to be ignored. Even the Loch Ness Monster has failed to do more than frighten and confuse a few tourists, and yet in return, its habitat has been violated over and over by fame-seekers whose antics have become the better part of the legend.

Monsters represent shame, and that’s part of what makes them so frightening. Facing shame – facing the possibility that your own actions have been wrong – is one of the worst parts of being an adult. Piling onto that is the fact that there’s not really any good way to make amends to a monster. The bomb has been dropped, the lake has been invaded, and unless you find a way to turn back time, there is no way to give your sewn-together corpse man a hug and tell him that he’s lovable. Your best option upon realizing that you’ve messed up to this extent is to retreat and sit with your guilt. And then don’t do it again.

As new horror genres emerge, it’s tempting to extrapolate how our fears will continue to evolve. From the racial terror of Get Out to Black Mirror’s technological angst, our tropes reflect stranger anxieties that we, as viewers, may be only now forming the desire to face. Just pray that they don’t come for you in your nightmares first.

READ NEXT:

– The Best Horror Games

– The Best Horror Movies

– 10 Underrated Horror Movies To Watch This Halloween

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.