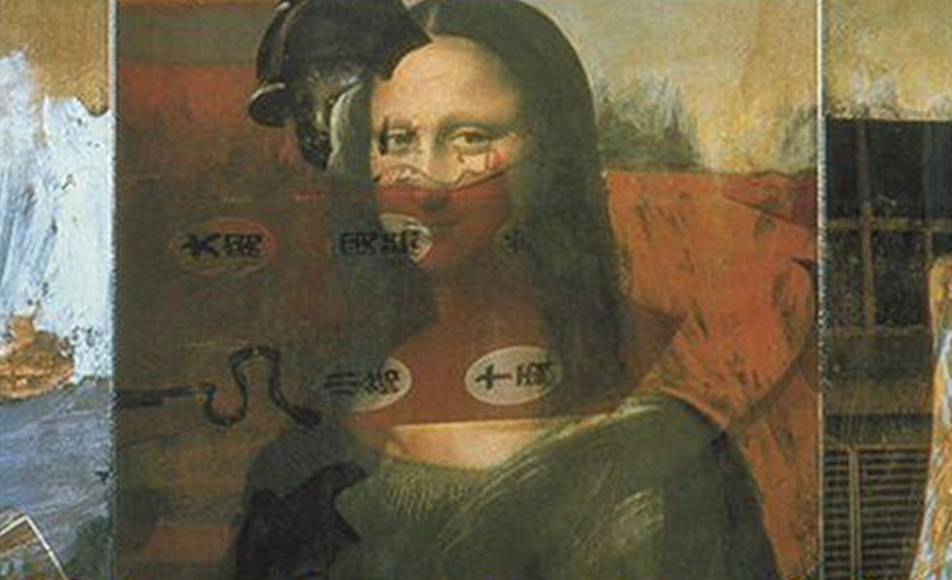

Robert Rauschenberg was a pioneer of contemporary art, experimentation, and kindness, and produced work all over the world with the ROCI (Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange). He lived among creators in countries struggling with some kind of disarray and worked with them to generate art inspired by and using techniques from their cultures. Rauschenberg, Art and Life is a detailed account of the processes the man and his art underwent to be established as a worldwide success.

It is about the artist as much as it is about the art, which is actually kind of rare for these sorts of books. However, it manages to stray away from simply recounting Rauschenberg’s life story and showing how he got the platform he did – instead, it describes the creative processes that lead to the many works he produced over his career.

His most impressive production, rather than being any particular piece of art, is the ROCI, to which he dedicated much of his time and effort. It was a kind of cultural exchange scheme, where the outcome was to befriend people and learn about their lives as much as it was to produce a new series of artworks.

Rauschenberg, Art and Life gives a new insight to the motivations behind this work, revealing that the artist sometimes faced boundaries regarding the presentation of his ROCI art but was always backed up by the people with whom he was working. He lived humbly in the same areas as his collaborators and earned great respect among them because of this.

The tale of Rauschenberg’s collaboration with John Cage, the composer and music theorist, particularly amused and interested me. The two were friends, and decided to collaborate on a piece called ‘Automobile Tile Print’ – it does pretty much exactly what it says on the tin.

Cage sat in his car whilst Rauschenberg laid out sheets of paper on the ground, and then drove over them, creating a thick tyre print across the width of the sheets. Rauschenberg later commented: “He did a beautiful job, but I consider it my print,” to which Cage replied, “But which one of us drove the car?”

The exchange between the two innovators opens a wider dialogue asking about the belonging and ownership of art, which again leads back to the ROCI art: are the collaborations simply Rauschenberg’s, since he set up the meetings and ultimately began the interactions with the other artists? Or can the nameless contributors claim equal ownership? Can the countries, even, and the cultures in which they were produced, claim some rights to the art produced in their land using their ideas and traditions?

Judging on the Rauschenberg presented in this book, he would have wholeheartedly agreed that his contribution was only part of the input seen in the final products. He is shown to have been a sensitive, aware, determined, and all-round nice person – making the artworks seen in the book even more interesting and likeable.

I was a fan of Rauschenberg before reading this book, and after reaching its end I am more confident in his experimentation and the mindset he left behind as his legacy. A wholly inspiring book with just the right amount of artistic interludes to the fascinating text.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.