It’s always hard to write about memes in any sort of journalistic context – not least because the field of hard news mentioning any given meme is typically a kiss of death, a vast red klaxon warning us all that the meme has officially been played out. After that, it’s like Steve Buscemi in 30 Rock wandering up with his skateboard and asking “How do you do, fellow kids?”, a moment which has itself become an unusually robust meme. Buscemi, though, had the advantage that he was crystallising an all-too-familiar approach of old farts who never got the memo that they’re past it. The vast majority of memes that ever even get off the ground tend to have much shorter half-lives – particularly, as mentioned, if mainstream news gets its filthy meathooks on them.

While actively attempting to create a meme generally results in a flailing embarrassment, if anything was ever tailor-made for memeification, it’s Bkub Okawa’s Pop Team Epic, or Poptepipic. Beginning as a four-panel online comic strip in 2014, it has since seen the release of two collected volumes of the comic, and, in early 2018, an animated adaptation.

It’s quite likely you’ve run into some of the more virulent memes Pop Team Epic has spawned already, and like Buscemi addressing his fellow kids, the common thread seems to be relatability. When someone condescendingly corrects your pronunciation, do you not privately conclude something along the lines of ‘ah, you are motherfucker?’. When a friend waxes lyrical on some obtuse pet theory, have you never had a moment of declaring ‘aah, so it’s like that, huh. I understand everything now’ while, in fact, still thoroughly lost? Do you know that feel? Yes, exactly.

(There’s also one strip which ends with Popuko in jail, having been ‘arrested for YouTube crimes’. To some, this is a kind of beautiful dream, to finally sort out the likes of Paul Logan – to others, uncomfortably prescient of the case of Mark ‘Count Dankula’ Meechan, who was indeed arrested and charged over a YouTube video, thanks to the United Kingdom’s laughably draconian laws regarding online communication.)

The series as a whole is composed of much of the same raw material as many of the best memes. It’s heavy on pop-culture references, drawing particularly on the worlds of video gaming and the internet – indeed, it’s so dense with references to Japanese culture it’s unlikely any Western viewer could fully understand it. It operates on a similar level of surreality to Monty Python at its weirdest, allowing the story to freely waltz through any number of unusual subjects and scenarios. Most importantly, there’s absolutely no continuity between one strip and the next. In much the same way as a Youtube compilation, if this one doesn’t tickle you, not to worry, there’ll be another along in a minute.

Our protagonists are the adorably chibi-style Popuko and Pipimi, two wide-eyed little schoolgirls. They’re a classic example of the small/tall comedy duo with clashing personalities. They’re also incredibly foul-mouthed, and, having carved out a niche for themselves in what passes for reality, dissuade anyone who threatens to interfere with extreme violence. Popuko is by far the more aggressive and excitable of the two, but for all that Pipimi’s more collected, she’s no less dangerous.

It’s not that Pop Team Epic is one of those series’ where the characters spend every waking moment fighting or preparing to fight, and the only theme is ‘AWESOME POWER’ – it’s simply that the girls have little to no self-restraint. Further, the whole work has a brash disregard for the common tropes and conventions of anime and manga written on its heart – exemplified by the show-within-a-show Hoshiiro Girldrop, a by-the-numbers high school romantic drama (“Fall in love again next week!”) which Popuko and Pipimi take particular joy in rudely interrupting.

Their inseparability and yin-yang personality archetypes, though, are as about as consistent as their characterisations get. Beyond that, they flit about as freely as the plots do, taking on whatever role is required, acting as anything from infants to wise old elders (at least, for a given value of wise) much like Bugs Bunny before them. To borrow the famous description of one-time Chancellor and Catholic martyr Thomas More, Popuko and Pipimi truly are men for all seasons.

The animated adaptation was, more than anything else, an opportunity for the whole thing to get even more outlandish. Okawa had done his best with pen and ink, but that’s a medium that simply couldn’t have captured dear little felt versions of the girls having a bit of a dance. Nor would it have the wonderful voice acting – both Popuko and Pipimi are voiced by two different actors each every episode. And while the grotesqueries of the corrupted ‘Bob Epic Team’ skits could have been conveyed as still images, it would lose something important not to see them in motion.

And yet despite all this wackiness, it would be a mistake to say there’s nothing else like it. Between the girls’ utter devotion to one another, which gets curiously intimate (as they’re children, one would hesitate to call it anything but Platonic, although they were married one time), the zany situations they find themselves in each and every week, and the pared-down, cartoony art style, it’s strikingly reminiscent of Akbar and Jeff from Matt Groening’s early work Life In Hell.

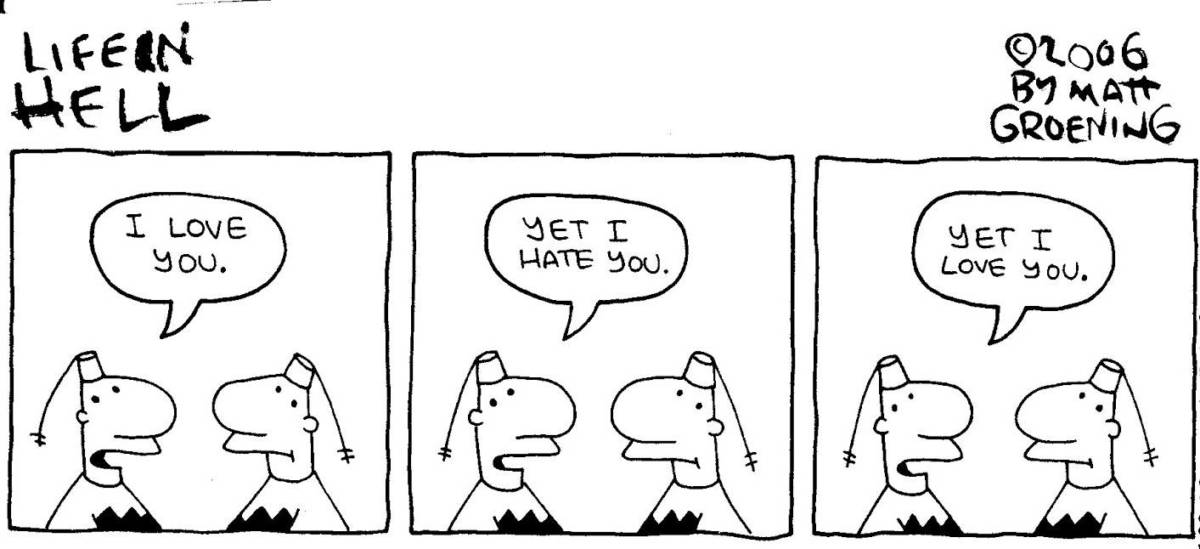

Akbar and Jeff were two identical fez-wearing men, memorably introduced as ‘brothers, or lovers, or both’. They had a taste for the lewd – especially dancing naked – and had a dysfunctional yet romantic relationship going on. While they got up to their share of zany schemes, with the strip covering many of their crooked business opportunities, like playing gurus who offered self-improvement courses with hefty price tags, typically you’d find them having extended dialogues about their own neuroses. This sounds more cerebral than it is, and usually took the form of either impassioned expressions of love, or trading vicious barbs in that inimitable way which – if you’ll permit me the stereotype – nobody does quite like gay men.

Akbar and Jeff – and indeed Life In Hell as a whole – never quite reached the level of surreal that is Pop Team Epic’s stock in trade, but it’s not a wide gulf. It should be said that the two works operate on distinctly different flavours of weird. When it comes down to it, Life In Hell was a holdout of ‘60s-era counterculture, whereas Pop Team Epic is rapid-fire reference comedy for the internet age. But nonetheless, even though they’re from very different ends of the earth, even though Akbar and Jeff are identical where Popuko and Pipimi are opposites, there’s a kind of spiritual kinship there.

(Groening was in talks to have Life In Hell adapted into an animated series, but, reasoning he didn’t want to sign the rights to his life’s work over to Fox, whipped up The Simpsons – which you may have heard of – instead. In this light it’s interesting to wonder what Okawa might have conjured up if he hadn’t wanted the industry’s claws in Pop Team Epic.)

The only difference is that Popuko and Pipimi are – despite the swearing, despite the violence, despite everything – incredibly wholesome as a duo. Not that there was anything wrong with Akbar and Jeff, but theirs was the definition of a love-hate relationship. By contrast, there’s a moment in the anime when Popuko has come up with a terrible new dance, Pipimi considers telling her it’s awful, and the mere thought of her upset is enough to have Pipimi not just heartily endorse it, but DJ to it.

It’s not just a nice change of pace to the rest of the series. It decidedly is that, but it goes further. In any work so fast-paced, that flits between subjects and references at such a rate of knots – and in this case a work which is always happy to describe itself as ‘shitty’ – there’s always the danger it’ll fall into a nihilistic state of nothing actually mattering. The rock-solid emotional core of Popuko and Pipimi’s relationship is a superbly applied antidote to that.

This depth may well be the key. The growth and spread of memes is an organic process, there is no one decision that decides whether a meme will or won’t succeed – no matter how hard one might try. Plenty of out-of-touch marketing types have discovered that. They can chuck as many supposedly meme-worthy things together as they like, and it comes off like Steve Buscemi wandering up with his skateboard, only not funny. Certainly, Pop Team Epic’s critics might accuse the series of being that sort of mishmash of cheap gags – and yes, there’s a lot of that in there – but there’s something more to it. Something greater.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.