The desire for positive representation of minorities in large scale movies has become a widely discussed issue over the past few years. From outrage over the cis Jared Leto playing a trans character in Dallas Buyer’s Club to the #OscarsSoWhite controversy and the lack of female directors working on big budget productions, representation in the film industry has been frequently debated. However, it seems to me that disability is often left out of the conversation, with discussions surrounding feminism, the LGBT community, and people of colour feeling more prominent. This is not to criticise or demean these movements, but I feel as though depictions of disability onscreen are few and far between, and in particular have made very little progress since cinema began, especially in the arena of romance.

Think of the most well-known disabled characters in film. Who comes to mind? Scarred and injured James Bond villains, seemingly embittered and vengeful after going through this implied suffering? Tragic figures like the Elephant Man in David Lynch’s titular film, defined entirely by his condition? Daniel Day Lewis in My Left Foot, an inspirational story that uses the protagonist’s plight to uplift rather than educate or provide a realistic sense of a person with the same condition’s abilities? I’m willing to bet that a conventional romance, in which the character’s disability does not define the relationship, does not factor in for most.

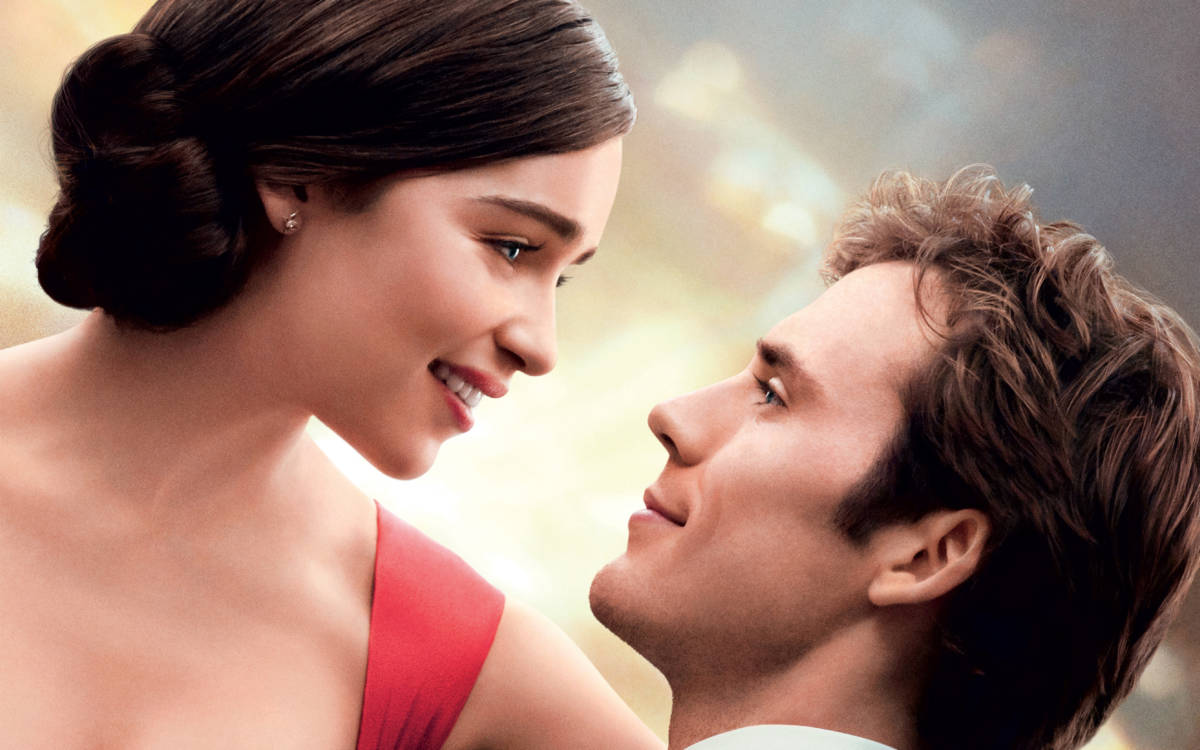

Upon its release in 2015, the British romcom Me Before You received some flack from both critics and online disability representation advocates for its controversial plot. A quadriplegic man falls in love with his carer, and eventually decides to kill himself, at least partially to ‘free her’ from having to take care of him. People were angry, and rightfully so; we receive so few depictions of disabled protagonists that having one who considers himself better off dead, a viewpoint validated by the movie, seems like a poor message.

The fact that Will Traynor, the leading man played by Sam Claflin, is overqualified in so many areas of traditional romantic interest also raises some questions. He is young, handsome, intelligent, cultured, extraordinarily wealthy and lives in a castle, and these traits come across to me at least as the writers desperately trying to make him as appealing as possible in every other area of his life. They create Will Traynor, the ideal face of disability. During his introduction to Emilia Clarke’s carer character, he even jokingly impersonates a non-verbal person possibly with cerebral palsy by making moaning noises, the writers desperately telling the viewer ‘don’t worry, he’s not one of those people!’.

While I appreciate that a large production company like Warner Bros. will release a film in which a disabled character is so prominent, the idealisation of his character and his fate do nothing for the genuine struggles of disabled people in modern society. Rather than addressing them head on, it pretends that they do not exist, and focuses on his sadness at no longer being able to ski or travel, activities exclusive to the wealthy that are likely irrelevant to the vast majority of disabled individuals worldwide.

However, this is not the first time that a film has depicted a relationship by a disabled and able-bodied person. Freaks, a 1932 movie about a little person at a freak show called Hans who marries Cleopatra, a beautiful able-bodied woman only after his inherited fortune, got there long before Me Before You. Unsurprisingly though, this ‘romance’ does not end well, and rather than both characters being sympathetic, the audience is obviously guided to root for Hans. The title may deem him a ‘freak’, but he is shown to be more traditionally moralistic than his wife, who shuns his friends during the infamous ‘one of us’ scene and is eventually given the ironic punishment of becoming a disabled ‘freak’ herself, but without a loving community to support her.

Unfortunately, the movie siding with the disabled characters at every turn only detracts a little from the otherwise voyeuristic tone. Many scenes are dedicated to different characters (who, unlike Sam Claflin, have disabilities and disfigurements in real life) going about their daily business, filming them not in an entirely disrespectful way, but with an implication that the audience is merely there to gawk. This assumption likely has a degree of truth, meaning that while Freaks was groundbreaking in terms of representation in depicting well rounded and sympathetic disabled characters, the content itself is undermined by the audience’s assumed mockery.

Obviously, both of these movies have some significant issues in their representation of disabled characters. Interestingly, they seem to succeed and fail in almost exactly opposite ways: Freaks is not afraid to depict a truly disabled person but in a not-too-flattering context, and Me Before You elevates the disabled protagonist to such an unreasonable degree that it begins to feel patronising. The way that Will in the latter is shot is certainly more flattering and appealing than most of the cast in the former, suggesting a level of progress in the eight decades separating them. However, the fact that they each show disabled characters at all in a context that demands a level of humanity and depth to how they are written is positive; though not fully realised, they are at least not completely dehumanized.

Both Freaks and Me Before You were released by major studios, MGM and Warner Bros. respectively, so these fairly unprogressive and simplified depictions of disabled characters in a romantic context could be explained by a desire to play it safe. A film that does not have this dilemma, and therefore takes far more risks in its portrayal of the protagonist, is The Way He Looks, an independent Brazilian movie from 2014. It follows blind teenager Leo as he tries to gain independence from his caring but overbearing parents, and to enter into a relationship in order to feel more like other teenagers. When he meets new kid Gabriel, Leo falls in love, and the burgeoning romance helps him grow as an individual.

This is a story in which the potency comes from the perspective; if the movie was from Gabriel’s point of view, Leo’s character would have far less depth. The slices of his life the audience are permitted to see, such as his walk home from school guided by best friend Giovana, his first shave assisted by his dad, and his inability to see when classmates are mocking him, lend his plight significantly more realism. Rather than idealising the character, we see him at his best and worst, from his sense of humour with friends and taste in classical music to his tendency towards laziness and his grouchiness around his well meaning parents. This, and the number of scenes with Leo and Gabriel that show their electric chemistry, make the film the best representation of a relationship with a disabled person that I have seen on screen.

Unfortunately though, others may not have seen it. Despite its availability on UK Netflix, The Way He Looks was not distributed widely upon release, nor given a large budget for marketing. This means that, despite its sweet, realistic, and respectful portrayal of a disabled character in love, nowhere near as many people will have watched it compared to the other two, far worse, examples in this article. That is the heart of the issue: films with positive portrayals exist, but not through mainstream means. Movies like The Way He Looks will have to do for now, but disabled people unaware of the independent film scene deserve to go to a cinema and see themselves in not just the protagonist, but the romantic relationship too.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.