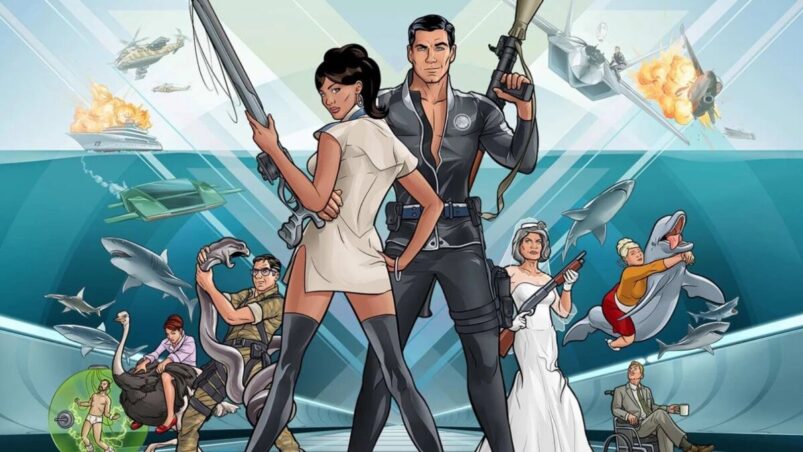

Twelve whole seasons isn’t a bad run, especially for a show which has spent most of its life competing for attentions and affections with contemporary animated titans such as Family Guy and South Park. Yet with the tragic passing of beloved star Jessica Walter, the voice of the titular hero’s overbearing mother Mallory, comedy spy epic Archer looks set to hang up its tactical turtleneck and Walther-PPK as Season 12 threatens to act as the satirical spy saga’s ultimate swansong. Even if this isn’t to be the last we see of Sterling and co., it feels fitting to look back on a show which has quietly gone about its business as one of the finest animated offerings of the past two decades.

Fans, critics and commentators have always been keen to categorise Archer as an outright parody, a send-up of the spy genre which takes aim at the likes of James Bond and his jet-setting, neck-snapping escapades for the sake of comedic effect. Although this isn’t inherently untrue, to label Archer a mere pastiche places the show alongside the likes of Austin Powers or Leslie Nielsen’s Spy Hard, i.e. affectionate spoofs which lift directly from the source material and then add in a few slapstick gags, is to underappreciate the depth and breadth of a world which lives and breathes as a sentient entity, a world which subverts, satirises, and celebrates the films and shows which so clearly inspired it. Indulge in the Archer-verse for a few seasons, and the richness of the show’s complexity becomes increasingly apparent.

Take the title character, Sterling Archer, a man whose codename, ‘Duchess’, derives not from a random process of selection or as a badge of honour resulting from his seismic covert exploits, but from the name of his mother (and boss’s) dearly deceased Afghan Hound. Superficially, Archer is James Bond in all but name, a seemingly romanticised masculine archetype whose reputation as the ‘world’s most dangerous spy’ precedes him wherever he travels, whose hair is so thick that his ‘barber charges him double’, and who, for the most part, finds himself to be irresistible to practically every member of the opposite sex.

Yet Archer’s idealised appearance belies a more grounded dysfunction which continues to unfold as the show progresses, from his miserable, bully-laden childhood at boarding school, his lack of paternal influence, and, of course, his completely warped relationship with his overbearing mother, Mallory. The latter, in particular, operates as a hyper-extension of the maternal figure of the spy genre, be it Bond’s ‘M’ during the Brosnan/Dench years or The Avengers’ aptly-titled ‘Mother’, with Mallory’s constant presence in her son’s life so restrictive as to be both comically rich and dramatically fraught as she suffocates his relationships and undermines his own fragile ego. As Archer’s series love interest and co-agent Lana Kana explains in the very first episode: “I dumped you because you’re dragging around a 35-year-old umbilical cord”.

What Archer himself represents, then, is the collision of an idealised male fantasy figure with the more grounded and realistic turmoil of how such a figure might actually live; superficially, Archer may be handsome, sharp, athletic and exceedingly desirable, but as a human being he is narcissistic, maternally dependent, a high-functioning alcoholic and, more often than not, a reckless danger to those around him.

Archer is not only exceedingly dysfunctional, he’s also immensely lucky, and it is this unparalleled fortune which operates as one of the show’s subtler critiques of the genre it satirises. Sterling is competently incompetent – things always work out for him despite himself and his efforts at self-sabotage. As each mission unfolds, Archer is revealed to be inhumanly capable yet also ludicrously arrogant, and it is this arrogance which threatens the success of his assignments, from failing to properly defuse a bomb because of his unwillingness to follow instructions to shooting a hole in his own boat while stranded in an alligator-infested swamp. In this unearned serendipity, creator Adam Reed and co. deconstruct their own heroic ideal: Sterling the man usually falls short, yet it is the archetype he represents which must always succeed to satisfy the rules of his world and genre.

The superspies of fiction always win out despite their own clear failings, be they alcoholism, womanising or just reliance on sheer dumb luck, failings which are downplayed or ignored at the expense of highlighting their bravery, their wit or simply the mere narrative necessity of their survival. Sterling’s failings constantly interfere with his missions, his rogue alcoholism and arrogant egomania making a deadly combination when trying to execute high-level international espionage. Reed and his writers ask not ‘how does this man do it?’, but press more deeply in querying; ‘how does this guy keep getting away with it?’.

When Archer isn’t deconstructing the mythologies surrounding its own principal protagonist, it’s also well at home critiquing those which envelop the supposedly lavish nature of his surroundings. Bond operates in a world of glamour, of fast cars, shining Mediterranean coastlines and bustling urban metropolises, in which he, of course, is conspicuously inconspicuous. Yet Reed often redirects the focus of much of his own work towards that which is unappealing to the eye and to the spy fantasist’s usual taste: drab, anachronistically-styled offices stuffed with outmoded terminuses and plywood desks populated with tired, faceless drones. Bookish accountant and bureaucrat Cyril Figgis may be our protagonist’s apparent antithesis, but the true world of spying is as much his as it is Archer’s.

Sterling’s employer, meanwhile, the unfortunately named ISIS, is itself an unglamorous corporation scraping to keep itself afloat, often the last resort for most of the clients who outsource to it and always in competition with other self-serving rivals. Archer is a show set in two contrasting worlds; one of high-stakes espionage, jet-setting adventures and impossibly beautiful women, the other of risk-assessment forms, dull office politics and décor that wasn’t even fashionable when it was installed thirty years ago.

The staff who populate these offices heighten this sense of bureaucratic claustrophobia through their sheer incompetence, ineptitude and all-too-human flaws, from unstable sociopath secretary Cheryl Tunt to mad (former) Nazi scientist Dr. Krieger. ISIS’s staff are incapable of operating as a cohesive unit, the ramifications of their actions leaving a more permanent impact than the mere trivialities which transiently follow the actions of a Bond or a Napoleon Solo. Reserved accountant Cyril, for instance, battles sex addiction for much of the show’s run, analyst and agent Ray suffers homophobic slurs from his reactionary boss Mallory, while Archer, on top of everything else, has developed severe tinnitus and picked up numerous STDs from too many guns and women respectively. The unglamorous repercussions of international spy work live side-by-side with the profession’s flashy exterior allure, the two contrasting worlds forced to coexist in one messy package.

It is these textures and contrasts which categorise Archer as more than a mere parody of its subject matter but rather a humorous deconstruction of a fantasy world which never truly existed. The flaws and foibles of the show’s eclectic and eccentric cast are windows into humanity rather than mere flipping of genre tropes. This isn’t to suggest that the show isn’t happy to indulge in these tropes when the mood takes it. Archer is as much a spy thriller as Spooks or Homeland, but a thriller which uses shades and nuance to craft a cohesive world, the enormous stakes of the high-octane spy thrills making the gang’s incompetent squabbling all the funnier without ever allowing it to undermine the excitement of the day’s action. Archer is happy to have its cake and eat it, with episodes indulging in familiar narrative devices before allowing the subsequent deterioration of team relations to throw a comedic spanner in the works.

That isn’t to say, either, that Archer is an unrelentingly cynical show. Because its characters have flaws, insecurities and varying degrees of arrested emotional development (perhaps fitting, considering the late Jessica Walter’s other iconic role as Lucille Bluth in Arrested Development), their co-dependence becomes as important to the overall narrative as their co-dysfunction. Archer truly loves on-and-off partner and fellow agent Lana because she is both maternal and exceedingly competent, and he shows a keen desire to defend best friend Pam when, for instance, her weight is mocked in a comparison to ‘Baby Huey’.

Archer never confuses dysfunctional with one-dimensional, either. Ray is gay but he’s never incompetent, cowardly or unrelentingly stereotypical, often standing up to Mallory’s bigoted barbs, while Mallory herself is over-protective and overcritical of Sterling not for mere pleasure but in order to keep her son dependent on her love. A warped form of affection, yes, but an understandably human motive all the same. As Mallory explains to Archer during a, let’s say, pivotal scene at the end of Season 10: “the real story’s always been about you and me…it’s really a love story”.

Whether you love it for its intrinsic qualities or for its perfectly measured skewering of the materials and genres which inspired it, the show’s pacey narratives, perfect characterisation, and zippy dialogue make Archer a gem on whichever level one chooses to enjoy it. If Season 12 does end up being the conclusion to the grand spy saga, it will bow out as one of the finest adult animated shows of the past twenty years. Not bad for what could so easily have been yet another Bond parody.

READ MORE: 15 Best Animated Shows of All Time

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.