In the spirit of April Fools’ Day, I want to highlight some great pranks that have played out in films, and I’m not talking about pranks that characters in a 1980s teen comedy would pull on each other. Instead, I want to think about how a filmmaker can prank their audience.

And how can a filmmaker ‘prank’ their audience? Well, how does a prank often unfold? The prankster sets up their target to believe something only to pull a bait and switch and reveal something else to be the case. A filmmaker can prank their audience by moving the film in one direction and building expectations, only to pull away and move in a different direction, subverting and rejecting those expectations in the process.

As film watchers, we have certain expectations about stories just based on what we have seen before. Skilled filmmakers can play off these expectations to lead the audience down a certain path, only to pull the rug out from under them and deliver a result that is wholly unexpected. Each film on this list exemplifies a filmmaker ‘pranking’ their audience and each of these pranks is integral to the overall greatness of the respective films. I am not sure these filmmakers pranked their audiences as a joke, but they certainly could revel in the way they toyed with the audience.

So, here are four great pranks on the screen from four great films. Spoilers abound, so proceed at your own risk.

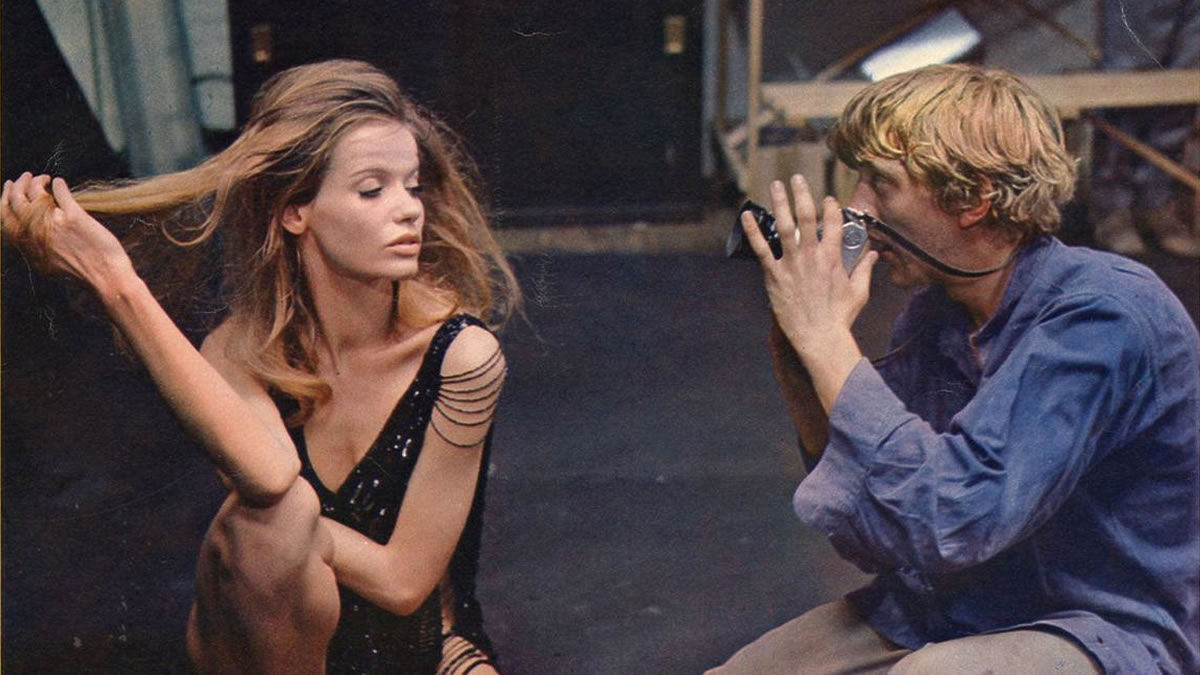

1. Blow-Up (1966) – Mysteries Without Answers

Michelangelo Antonioni made a career out of false climaxes that left the audience unsatisfied. His films set up exciting plot threads only for them to be ignored, leaving satisfying conclusions out of reach. Blow-Up is very representative of this pattern.

The protagonist is a young, arrogant fashion photographer. As he develops a set of photos he took in a park he realizes that he has captured a murder on film. He returns to the park and finds the body exactly where he expects. The photographer attempts to investigate the mystery only for his photos to be stolen, and his friends are all too aloof, too self-absorbed or simply too high to care.

At the film’s conclusion, he returns to the park to find the body gone and he aimlessly wanders an empty field alone. An intriguing murder mystery is set up but not delivered on, with no answers to the questions, no grand conspiracy to unravel and no thrilling climax to be had. All that’s left is an overwhelming sense of emptiness, for both the protagonist and the audience. As the audience, we always expect mysteries to be wrapped up nicely and for our questions to be answered. When we are denied this, it’s frustrating, but this denial is essential to the lasting emotional impact of Blow-Up.

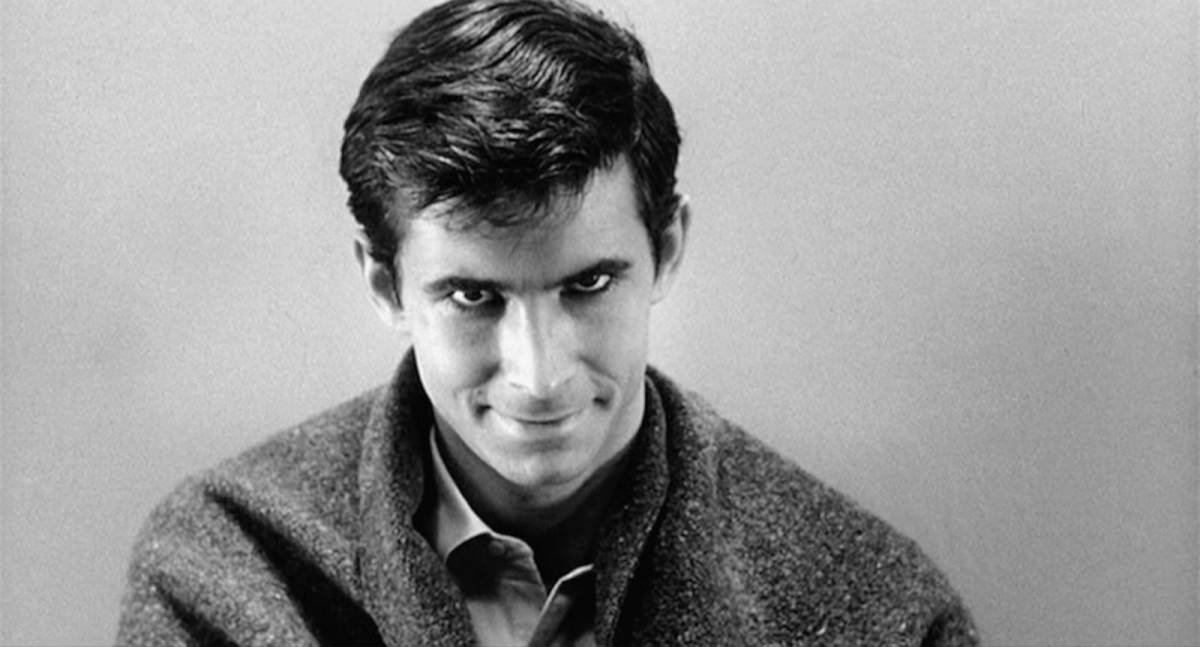

2. Psycho (1960) – The Lost Protagonist & Plot

The famed final twist of Psycho might be more expected to get a mention here, but that twist doesn’t truly shift the direction of the film. Instead, it’s the earlier twist, the death of Janet Leigh’s Marion Crane, that changes the film’s narrative course.

Viewed in a vacuum (i.e. without prior knowledge of the plot) the opening half hour of Psycho heads in a very different direction than the rest of the film. We see Crane steal money from her employer and run away with it, and Psycho’s early scenes are completely dedicated to Crane’s flight and all the tension builds out of her fear of being caught. We expect the film to continue following this narrative strand, but Crane’s murder reverts that plot thread to a side note.

A key part of Psycho’s brilliance is the way it utterly and completely shifts direction by killing off its leading lady such a short time into the film. The audience naturally becomes emotionally connected to Crane and her story, but Hitchcock yanks this story away from us. The way he shifts gears so suddenly and bluntly keeps the audience on its toes in a way that no other director can.

3. Funny Games (1997) – Teasing The Audience

Funny Games is probably the most direct example of a prank on this list, no matter which version you watch. Michael Haneke’s film(s) follows a mother, father and son who are spending a family vacation at a lake house when two intruders arrive. This pair of cruel prep boys have savage fantasies resembling the likes of American Psycho or the Purge franchise. The villains proceed to play the titular games with the family as they torture them, while Haneke plays games with the audience.

As we yearn for the family’s escape, Haneke continually teases their freedom / safety before yanking it away at the last instance with fourth-wall breaking moments that mock basic conventions of storytelling. In one scene, a knife is shown to be within the grasp of the mother and as we desperately hope for her escape, one of the villainous duo tosses the knife away before smirking at the camera and mocking the audience’s naivety.

In another scene, the family defeats their captors only for the film to literally rewind to allow the action to replay with a less desirable result. Haneke doesn’t just dash the audience’s hope, but he allows his villains to break the fourth wall and openly tease the audience in the process.

4. Mulholland Drive (2001) – It Was All A Dream

‘It was a dream the whole time’ is perhaps the most quintessential filmmaker prank, but no film pulls it off as brilliantly as David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. Most films that include the dream prank want the dream sequences to closely resemble reality so that the audience is fooled into believing it is reality. Alternatively, Lynch’s scenes are disjointed, awkward and abstract so that they more closely resemble a dream than anything else that I personally have ever seen on the screen.

The first two hours of Mulholland Drive are set in the dream, so we have no moments of reality to compare it to and no indication that it is, in fact, a dream. This narrative decision, combined with Lynch’s notoriously weird style, keeps the audience fooled.

There is something recognizable but foreign to the majority of this film. It’s only when the reveal finally occurs that everything clicks into place and the brilliant representation of a dream becomes so obvious. Lynch presents the most authentic example of a dream on film and hides it so that when we realize what we have been watching, its genius shines through even more brightly.

READ NEXT: Make the Case: 5 (Reasonably) “Feel-Good” Movies

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.