In the last five years, Damien Chazelle has solidified himself as the most exciting young filmmaker in Hollywood by embracing the basic joys of classic cinema and the elegance of a simple story with complex characters. His three films, Whiplash, La La Land, and First Man, all share a similar driving force. They are all unique, but there is an everpresent undertone in all of his flicks that is about one innate aspect of life – ambition, and the consequences that lie behind the gleam of success.

Chazelle’s works are remarkably tuned to consequences, and if you know him, you know his films may not end with a happily-ever-after. The “old hollywood” storytelling of William Wyler or Frank Capra is embraced, and then shattered, elevating simple, well-executed stories into masterpieces. It is in defying expectations that memorable films are created. Casablanca would not be remembered if it bowed down to the expectations of simple, satisfying romance. Chazelle knows this, and uses expectations to create three completely distinct stories that all relate in an incredible way.

In Whiplash, Chazelle’s first big-budget outing, Andrew Neyman (Miles Teller) is completely consumed by his efforts to become the best drummer in the world. He goes to a fictional, bespoke school of music in New York, and is met with a terrifying force by the name of Terence Fletcher (J.K. Simmons). Fletcher abuses his students, especially Andrew, and drives him close to the breaking point. Andrew’s blind determination is almost intriguing to Fletcher. This jazz musician is so focused on greatness that he risks everything that matters to him.

His relationship with his father is stressed, he loses any hope with the girl he is interested in, and he arguably loses his sanity. The integrity of jazz is also threatened, and his relationship with music itself is put to the test. Chazelle says in an interview that he “wanted to look at the mentality that can breed that sort of intensity, that kind of cutthroat, pressure-cooker feeling, especially a form of music like jazz, that should be – or you’d think should be – all about liberation and improvisation and everything.” This sense of freedom in art is lost; it is condensed, squeezed out of Andrew in the pressure cooker atmosphere of his school.

This is Chazelle’s most visceral, traumatic look at the human desire for recognition. Andrew claims that he would “rather die drunk, broke at 34 and have people at a dinner table talk about [him] than live to be rich and sober at 90 and nobody remember who [he] was.” Andrew may have achieved the former; he ends the movie a broken man, having nothing left but respect. What is Chazelle saying about this drive? We get a better picture of his mindscape in his later films.

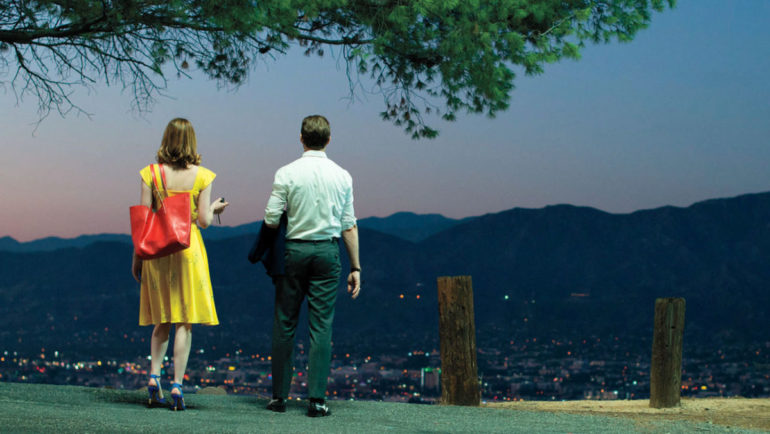

In La La Land, we are treated to a completely different kind of dream. Mia (Emma Stone) and Sebastian (Ryan Gosling) both aspire to find happiness in their work, both as an actress and jazz pianist, respectively. They balance a line between fantasy and reality, making sacrifices for the longing of adoration and embodying a romantic view of life. It is Singing in the Rain, it is Casablanca, but it is all grounded with a shocking amount of realism. One second they are Humphrey Bogart and Audrey Hepburn, and the next they are a failing jazz pianist and a broke barista. Their ambition is to break free from this dreary monotony of life, and both Mia and Sebastian are unfortunate stepping stones on each of their paths to freedom. Chazelle treats us to a movie about true love. However, this love is not only between our leads. It is a love for fantasy, for escapism; love for Hollywood.

Mia and Sebastian need each other, but they need the world that they dream of more. Chazelle says, “It’s interesting when you wind up distilling all your ambitions and your goals and dreams into one single person. It’s giving that person a lot of power.” A giant house of cards is built with this power between them that crashes into cinema magic in the final scenes. It is tragic, it is joyous, and it forces the audience to question what priorities they have that they are willing to sacrifice. Only the very rare film leaves the audience with a message that they have to discover on their own. A flame starts because of Mia and Sebastians friction, and once they are separated, the fire burns on.

First Man is about mankind’s unstoppable thirst for achievement and its impact on a simple man. This is different, but it caps off Chazelle’s first trilogy beautifully. Ryan Gosling is the leading man again, this time playing the reluctant hero, Neil Armstrong, with Claire Foy as his wife, Janet. Neil and Sebastian are just as similar as they are different. They are both extremely passionate, however, Seb is brash, while Neil is reserved. This true story, adapted by Chazelle, has a vastly different mood than the triumphant success story we have come to expect about the moon landing. It is split between a historical account of the events leading up to the moon landing and a deeply personal tale of Neil Armstrong coping with the loss of his daughter and the strain on his marriage and family.

This split leads to some thematic confusion, but it comes together in laser focus in the last 30 minutes. It is intensely loud, and intensely quiet. Tension comes to a head after the deaths of the Apollo 1 crew, and Janet is frustrated at Neil’s persistence to continue with his mission to the moon. Chazelle spotlights the hesitant culture around risking more lives in the pursuit of discovery. Taxation, racism, and death surrounded the program – mankind was struggling with the consequences of large scale ambition for ambition’s sake.

Neil lands on the moon (spoiler alert), and seemingly resolves his trauma about his daughter’s death, but is met with a somber scene in quarantine when he arrives back home. Chazelle once again astounds with his final scene. A man who has just achieved history is desperately searching for peace and forgiveness for the stress that he has inflicted on his wife and children. This reconciliation between family and dreams is once again explored.

In all three masterful endings, he lets his actors and the music do the talking, and it says much, much more than words. He relies heavily on excellent acting and perfect editing to give us a bittersweet conclusion we can think about long after the credits.

In every film we are asked one question in different ways – “Was it worth it?” How much is one willing to risk to go to the moon? To become a successful musician? Actor? “Why, some say, the moon?” JFK asks, “Why climb the highest mountain? We choose to go to the moon this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

These questions are never directly answered by Chazelle’s work. He doesn’t hold our hand and tell us what to think. He says, “I always wanted to make movies about fever dreams.” These are not always clear cut pictures grounded in reality. Whiplash and La La Land both have a heightened sense of art and passion, they are exaggerated portraits that are just as fantastical as they are realistic. The dreams explored by these works are magnified, larger-than-life myths that can result in either great success or great failure.

All of these dreams come at a cost, but the message is not a cautionary one.

Chazelle does not tell us to avoid ambition. He actually encourages it, and in First Man, he proclaims ambition as necessary. He is wholly aware of the end. Chazelle is famous for his finales because that is where we see the full realization of this beautiful compromise. He never babies us with Hallmark movie pleasantries. He gives us characters like Andrew, Seb, Mia, and Neil, who are grandiose stars in our eyes.

All heroes must sacrifice something, without sacrifice, there can be no achievement. These are our idols, they have sacrificed to achieve. They are dreamers, searching for a life outside of their own. They have overcome a world that does not always appreciate them, a world that “worships everything and values nothing.” They have overcome mental punishment, they have overcome heartbreak – they have overcome the stars.

So here’s to the fools who dream.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site.