Nirvana’s concert at the now deceased Satyricon club in Portland, Oregon on January 12th, 1990 was one of the most important concerts of the band’s brief history, but for 25 years we had no idea what that concert actually sounded like.

The concert is most famous for being the night Kurt Cobain met Courtney Love, but musically it’s important because it was one of the first times “Polly” and “Breed” were played live. This concert was also one of the last Nirvana shows before Dave Grohl became the band’s drummer, which essentially turned Nirvana, the local grunge favorites, into Nirvana the band that would knock Michael Jackson off the number one spot of the Billboard 200.

So why are we just hearing this show 25 years later?

My guess is that Nirvana back then was just another struggling grunge band trying to get by. Their debut album Bleach was critically acclaimed, but it was only a modest hit, so there probably wasn’t a strong need among fans to record this or most of the other shows during this band’s murky early past (It seems that, for most people, Nirvana’s history begins at “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and not “Love Buzz”).

However, there was one person, known only to us as YouTube user WY97212, who was at that show and who recorded the entire set. Whether he wanted a copy of the show for himself or to sell it to others is not known, but the recording was kept away and life moved on.

But now, 25 years later, WY97212 has released the recordings of that show, and we now have a new insight into a pivotal moment of music history. And it’s all thanks to bootlegging.

Music bootlegging, specifically in the rock era, means to record, audio or video, a live performance that an artist hasn’t officially released, or it’s the unauthorized distribution of unreleased music. It is both a blessing and a curse, depending on how you view the value of music and whether you believe you should pay for music through an “approved” distributor. In their defense, bootlegs give an unbiased view of an artist by simply focusing on the music, without any sort of agenda that skews the experience that tends to come from a music journalist or a promoter.

A bootlegger can be one of many different kinds of people: fans innocently recording a show for personal enjoyment, free-marketers giving fans what they want and giving a big “Fuck You” to the record labels, friends of the band who are recording the show for an upcoming “authorized bootleg”, or conniving schemers who want to make a quick profit at the expense of the band. But no matter the intent, most of these people probably aren’t thinking about capturing a special moment when they are recording these shows. When WY97212 was recording this Nirvana show, I’m sure had no idea that, 25 years later, his recording would give insight into the early history of one of the most famous bands of the 90s. He was probably just a fan who wanted to record a show he was enjoying, or he knew that a lot of people would pay to have a recording of this show. But he did what only bootleggers can do – preserve history.

Bootlegging can also define certain artists by how strongly they embrace or oppose their music being shared without their total control. Some artists encourage fans to share their music by any means possible, and some bands even promote bootleggers to record and share their shows (Pearl Jam and the Grateful Dead are great examples).

However, other artists feel that they should be properly compensated for their music, and they will try and hunt down and punish any bootlegger that they can find. Both sides have valid points, but it tends to be the artists who strongly oppose bootlegging that seem totally oblivious to their value; there’s no quicker way to lose fans than to punish them for wanting to hear and share your music.

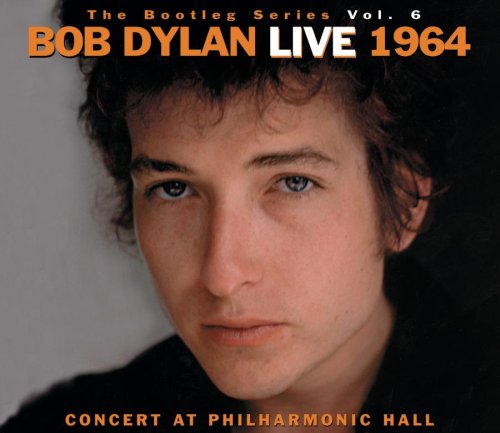

The best example of someone who embraces, and benefits, from bootlegging is Bob Dylan. The folk troubadour has so many hours of unofficially released songs that there is an entire album series devoted to just his bootlegs. You can even say that Dylan invented music bootlegging for the rock era when, in 1969, a collection of unreleased Dylan home-recordings known as The Great White Wonder became one of the first major popular albums of unreleased music to be shared among fans that wasn’t technically authorized.

The scary part of Dylan’s Bootleg Series is not its size (the series is currently on its 11th album), but rather how many of those albums sound better than many of his proper studio albums. One of them is even considered one of the best rock albums of all time.

But these albums are enjoyable for the reason that most bootlegs are enjoyable: they offer an insight into a unique time that, for the most part, is unedited. Perhaps Dylan’s most famous bootlegged moment is the “Judas” heckling that you can hear from the 1966 “Royal Albert Hall” concert, which also happens to be one of the greatest live albums of all time (though it was actually recorded at Manchester Free Trade Hall – you still have to be careful about the accuracy of bootleg titles). Now I’m sure that Dylan’s record label would have edited out the “Judas” bit, but thankful we have that piece of unedited history. We usually don’t go to bootlegs for the quality of the sound (most bootlegs understandingly sound awful), but rather for what they can offer to the context of the music.

And then you have someone like Prince, who will sue fans millions of dollars for any kind of unauthorized sharing of his music. Again, it’s easier to hate Prince than Dylan because of how they each handle bootlegging.

In 2015, when anyone can record a show and upload it to YouTube, the bootlegging industry is still thriving. Now many people will classify online music streaming as a type of bootlegging, in the sense that an artist is not properly being compensated for their work, but the two are not the same. The issues with music streaming usually concerns where you’re hearing the music, but with bootlegging it’s all about what you’re hearing. It wouldn’t matter if you heard Dylan’s “Royal Albert Hall” concert on a YouTube video, a Spotify stream, or an iTunes player, because without bootleggers there would be no concert to stream in the first place.

The Nirvana show was taken down from YouTube due to copyright issues, so record labels and bootleggers have adjusted to the advancement of technology and continue to fight each other. There is no telling what the future of bootlegging will look like, but it’s safe to say that we will always have bootleggers, and we’re all the better for it. So the next time you’re at a rock show and you’re enjoying a young band, you might want to record the show. Because you never know.

Some of the coverage you find on Cultured Vultures contains affiliate links, which provide us with small commissions based on purchases made from visiting our site. We cover gaming news, movie reviews, wrestling and much more.